”This is what brought me to my actual final mission. Not suicide, but a mercy killing.”

… by Katherine Ainsworth

[ Editors Note: This is Katie’s first article for VT. There has been a lot of writing about this issue, but she brings something different to the table. She is better than most of the others, so she will be right at home here. Katie has also experienced this issue up close and personal, and that provides an insight that cannot be gotten any other way…but an education with a high tuition.

As always, we are keeping an eye out for new writing talent that is worth the time of busy readers, which our VT audience certainly is. Be sure to read her bio that I have put at the end. This is an unusual lady and we are looking forward to a good body of work from her… Jim W. Dean ]

_________________________________

The tranquil white house in Wisconsin looked like any other. A neatly mowed yard and carefully maintained exterior spoke of pride in appearances and dinner simmering in a crock pot in the kitchen spoke of coming family time.

Just like other nights, tonight the Magdzas – father Matthew, wife April, 13-month-old daughter Lila, and the unborn baby April carried – would sit down to dinner.

But tonight was different, because the next day, April was scheduled for a c-section to deliver their second daughter, Annah. The August evening should have been full of joy and excitement, but instead the specter of death permeated the Magdzas home.

Before dinner could be eaten, before the possibility of an evening bubblebath for Lila and before the family’s dogs could beg for leftovers, Iraq war veteran Matthew pulled out a 9mm handgun. First he shot his pregnant wife, then his newly toddling daughter – and then he shot all three of the dogs.

After murdering his entire household, he turned the gun on himself. When investigators arrived at the grim scene they immediately called for medical help, fervently hoping to save unborn Annah. But it was too late for Annah. It was too late for all of the Magdzas.

Three years later, 30-year-old Daniel Somers, also an Iraq war veteran, found himself at the end of his proverbial rope. Before taking his own life, he wrote a note, the bulk of which was clearly meant to comfort his wife.

”This is what brought me to my actual final mission. Not suicide, but a mercy killing,” he wrote after detailing the nightmares and emotional scars he suffered after his service. His note included laying the blame at President Obama’s feet, asking why more was not being done for veterans.

Only one month later, a search was instigated by an understandably frantic mother after she received the following text: “[I am] a waste of oxygen on this earth”.

Her son, Army veteran and National Guard member Erik Jorgensen, was found dead of a self-inflicted gunshot wound at the Orchard Training Combat Center in Idaho, where he lived.

The three veterans resided in different states, had differing marital and family statuses and took wildly varying tacts in their deaths: a family annihilator, a man trying to comfort his wife even after death and a single man dying alone in a parking lot.

Magdzas left no note, Somers left a long, detailed one and Jorgensen sent a text message. No veteran’s life is so small and unimportant that it can be condensed into the body of a cellular phone text message.

These men had one thing in common: all suffered from Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD).

According to the American Psychiatric Association’s (APA) Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5), there is a specific set of criteria for PTSD. Those having experienced a traumatic event including exposure to death, the threat of death or an actual or threatened serious injury are at risk of PTSD.

What if a person has experienced not one but all of these things? In the DSM-5 Criterion A: Stressor, potential instances of exposure include direct exposure, witnessing an event in person, indirect exposure through a friend or relative’s personal trauma or repeated indirect exposure in the course of duties.

What if a person experiences every possible type of exposure? Skipping down to Criterion E: alterations in arousal and reactivity, at least two of the following six post-trauma reaction changes are required for a diagnosis: aggressive behavior, self-destructive behavior, hypervigilance, an excessively exaggerated startle response, difficulty concentrating and disturbed sleep. What if someone has not just two but all six? It seems veterans are doomed from the start.

PTSD has become an epidemic. And although the military has begun taking steps to better diagnose and treat it, it remains stigmatized. It is a four-letter word, both literally and by perception.

In 2010, the statistic for diagnosed cases of PTSD in returning veterans was 20 percent.By 2012, the number had jumped to 35 percent, and many express fear the rate could climb as high as 50 percent in 2013.

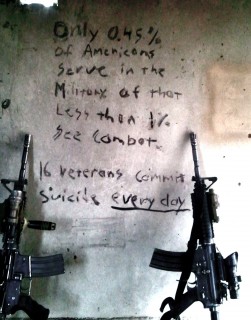

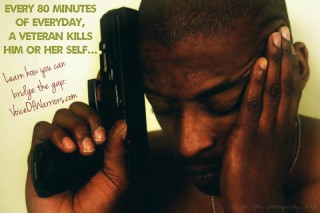

But perhaps a more frightening trend is the rate of veteran suicides, which Veteran Affairs (VA) placed at 22 every day as of February 2013. Every 65 minutes, a veteran takes their own life. And at least 1 soldier lost to suicide every day is on active duty. Veterans with PTSD are four times more likely to commit suicide.

So what has changed to cause this continual rise in veteran suicides? Why are Iraq and Afghanistan veterans so much more likely to commit suicide than Vietnam-era veterans?

We know it is not duration of deployment, because Vietnam veterans spent year in country without any breaks at home like today’s soldiers get.

And, in anything, war is carried out more efficiently now thanks to technology and knowledge born of experience.

According to professionals in both the field of psychiatry and long-time military members, it may very well have to do with the way today’s generation of soldier was raised. The young men who went off to fight in World War II had far greater responsibilities and faced more significant hardships due to the Great Depression.

And just as the nation’s worst economic crash to date crawled to a close, we entered World War II. Those fighting in Vietnam grew up exposed to a great deal of hatred and violence as the Civil Rights movement reached its peak.

According to David Rudd, the scientific direction of the National Center for Veteran’s Studies, “My worry is that they have not dealt with enough challenges, enough disappointments, in life for many of them to build the kind of resilience that is foundational when you go to war.”

How do you build that resilience? Through adversity and difficulty. Going through trials and tribulation, while a terrible experience no one wants to see repeated, granted young men in the 1940’s the coping skills necessary to mentally survive war.

That’s not to say that today’s young people are any less valuable than their successors but simply that they have, by and large, suffered far less adversity.

All parents want their children to have easier lives than they did, but an easier life can also mean a lack of resilience. Being taken from a fairly lax childhood and being thrust into the cold, hard realities of war takes a toll on everyone.

Of course, the military itself is partly to blame for its soldiers lack of coping skills. Soldiers are taught explicitly to cover ‘the six’ of all their fellow service members.

They’re trained carefully to protect one another, to be aware of their surroundings and what to do if all hell breaks loose.

But perhaps one of the most important things is one they are not taught, and that is how to take care of themselves. Sacrifice is a natural part of most military member’s makeup, and it seems that for many of them, they sacrifice themselves until there is simply nothing left. Perhaps fewer would be lost if there was more focus on personal coping mechanisms.

The military has increased its PTSD and suicide-prevention programs, even having returning soldiers fill out mental health evaluation forms. But even with the significant increase in seminars and pamphlets urging active duty soldiers and veterans to seek help for mental distress, a stigma remains. Soldiers are painfully aware of the disdainful way they may be treated by admitting they need help.

When being interviewed about his personal views on soldiers with PTSD, one Sergeant told NPR, “I don’t like people who are weak-minded.” Many soldiers admit refusing to seek help because they do not want to appear weak or because, they say, those that do look for mental health help are literally hazed when their issues come to light.

Officers admit using this method to “cull the weak from the herd”. Perhaps the stigma attached to PTSD has been lessened – and perhaps it has not. Maybe the spike in suicides is directly linked to that stigma.

Change has to come from within when it comes to removing that stigma. It should be a logical step given the bare fact that soldiers with good mental health can function far better both during and after service.The healthier its members are, the better the military is able to function. And the better the military can function, the more effective its actions will be, both big and small.

But suicides continue to rise, the numbers creeping higher each month. Multiple deployments create men and women who spend long stretches of time continually on high alert.

This hyper vigilance causes serious mental strain, and although one might think returning stateside would alleviate the problem, they’d be wrong.

Most service members struggle to acclimate to “regular” life. Forty years after Vietnam, veterans retain the constant awareness of their surroundings that got them home from war alive decades ago.

For many – no, for most – there is no return to normalcy. Their normal is the criterion for PTSD: aggression, hypervigilance, insomnia and an exaggerated startle response.

So perhaps expecting veterans to acclimate themselves to civilian life is an unrealistic demand. Instead of trying to force themselves to return to their pre-service realities, maybe veterans need to learn to function within their new parameters. Learning to function mentally and emotionally with a far different mindset than they had prior to their service is an important skill set. One that could save lives.

If the key to not only halting the rising suicide rate but turning it around is in teaching veterans to stop fighting their service-borne instincts, where would we begin? The human mind is not built to survive a constant state of readiness. But it’s unrealistic to expect veterans to simply turn off the very behaviors that saved their lives in combat.

Learning the coping mechanisms not to simply rejoin civilian life but to find a healthy balance of the old and new is a vital step. Of course, admitting the need for help is the first step, and, for many, that requires the removal of the PTSD stigma. And here we come full circle.

There is an undeniable link between the PTSD stigma and the suicide rate. As troops are brought home, they need help but are often afraid to ask. And when their need reaches crisis level, it is frequently too late. Suicide is increasingly seen as the easiest treatment.

Americans owe it to the veteran community to provide the help they need to survive. The men and women who have written blank checks for Americans, up to and including their lives, deserve our gratitude and our help. Allowing the suicide rate to continue unabated is not only a tragedy but a travesty.

Editing: Jim W. Dean

________________________________

Katherine was first published at the age of ten in a national magazine and has continued to write for a variety of outlets both print and web-based. She focuses her writing on military and veterinary issues. Her paternal grandfather was a highly decorated WWII veteran and her paternal grandmother was a WWII WAC. She began volunteering as a platoon mom with Adopt-A-Platoon more than a decade ago which began her personal military involvement.

Now she also volunteers with Soldier’s Angels and is working within the MWD (Military Working Dogs) and CWD (Contract Working Dogs) communities to bring awareness to the countless retired military dogs in need of homes.

Losing a loved one to PTSD has led to her taking a special interest in working to remove the stigma surrounding PTSD as well as raising awareness of the need for more help within the military community.

Her extensive work interviewing and writing about service members has resulted in her being labeled a “female Father Flanagan for wayward warriors” by one Vietnam veteran, a title which has stuck.

Katherine has more than fifteen years of experience in the field of veterinary medicine with specialties in small animals and emergency medicine. During her undergraduate studies in Biology at California Baptist University, she regularly made the Dean’s List for academic excellence.

She has nearly a decade of K9 Search and Rescue experience and is an avid outdoorswoman. She has been competing as a triathlete and competitive runner since 2002 and also practices hatha and Bikram yoga.

In addition, she has spent more than seventeen years honing her skills with firearms and is an experienced marksman. Katherine is a gun-rights proponent, a member of the NRA and a member of the Washington Arms Collectors (WAC). She is active within her political party and believes in the importance of fighting for what she believes in.

__________________________________

Jim W. Dean was an active editor on VT from 2010-2022. He was involved in operations, development, and writing, plus an active schedule of TV and radio interviews.

ATTENTION READERS

We See The World From All Sides and Want YOU To Be Fully InformedIn fact, intentional disinformation is a disgraceful scourge in media today. So to assuage any possible errant incorrect information posted herein, we strongly encourage you to seek corroboration from other non-VT sources before forming an educated opinion.

About VT - Policies & Disclosures - Comment Policy