A Clash of Cultures: Veterans and Non-Veterans in Academia

A Clash of Cultures: Veterans and Non-Veterans in Academia

by Robert L. Hanafin

Back in October 2010, I posted an article announcing that a group of College Professors and students – who happened to be Veterans – united to address problems beyond financial aid that they observed Veterans having adjusting to returning – or going to some colleges and universities for the first time – College Educators for Veterans Higher Education (CEVHE)

Although I do not totally agree with all their findings, as a Vietnam Vet who used the Vietnam GI Bill to go to college from 1973 to 1977, and the mid-1980s, I did note several insightful observations of my own that I could relate to: (1) The concerns expressed by professors and college bound Veterans applied not only to the academic and campus environment, but also to transition back to civilian society in general. (2) Many points made about problems experienced on a college campus are comparable to problems found adapting to a civilian job, a civilian community, or American society and culture in general. (3) Despite all the We Support Our Troops rhetoric from all sides of the political spectrum, our troops, especially when they become Veterans have been and remain remote and isolated from the rest of our society. (4) If we think hard about it, many of us who transitioned from the military to civilian society be it during Vietnam, the Gulf War, or now – even had, or have, difficulty relating to our extended families who had no experience of what military service especially combat) was like. It would be fair to say that despite the stress and trauma we put our immediate families through with the multiple deployments and such even our spouse and children cannot relate to our deployment experience, and in most cases we prefer they not relate. There are more than enough indoctrination programs to make our military families left behind understand multiple deployments but the actual experience itself is not the same.

Dr. Douglas Herrmann – one of the founding members of CEVHE – sent me two books to review and give feedback on, and although I read both, the one I preferred was Improving College Education of Veterans, because the chapters in it could be applied to any civilian environment our troops our veterans must integrate back into.

Dr. Douglas Herrmann – one of the founding members of CEVHE – sent me two books to review and give feedback on, and although I read both, the one I preferred was Improving College Education of Veterans, because the chapters in it could be applied to any civilian environment our troops our veterans must integrate back into.

The chapter I liked the most was Chapter 15 – A Clash of Cultures: Veterans in [Academia], and I’ve receive permission from Dr. Douglas Raybeck – another founding member of CEVHE – to reprint his views on the cultural clash between Veterans and Non-Veterans on college campuses. However, I want readers to think about how what Doug Raybeck says fits most any transition situation any Veteran would have to adapt to.

My apologies upfront for this being a LONG ONE, but I felt that breaking it down any further would lose both the flow and continuing of the main points Doug Raybeck is trying to get across. I did edit out my commentary and notes and placed them in the comments section below, so that what you read from here on are the sole views of Dr. Raybeck in his words.

ROBERT L. HANAFIN, SP5, U.S. Army (69-77), Major, U.S. Air Force-Retired (77-94), U.S. Civil Service-Retired, Veterans Issues Editor, VT News

IMPROVING COLLEGE EDUCATION OF VETERANS

Chapter 15– A Clash of Cultures: Veterans in [Academia] By Dr. Douglas Raybeck [Pages 179-195]

“Ninety-seven percent of [college] students, faculty, and administrators lack a military background. Some of these individuals are naïve about the military, and can be insensitive, and even offensive to service members and veterans. The problem stems to be largely a cultural one, a clash of cultures between academics, military and non-military members of the academy, all of whom have their own worldviews. The nature of the challenges encountered by student veterans is examined [in this chapter] and some means of alleviating these are suggested.” Dr. Douglas Raybeck

The problems enmeshed in the introduction of [Veterans] to academic environments are both numerous and complex. It is my belief that the principal difficulties involved in resolving these issues stem from different cultural backgrounds, filters, and perceptions. Cultural differences can be particularly [difficult to deal with or solve] because some of their strongest elements are not accessible to the consciousness of the participants. Stated another way, most of us are unaware of at least some of our cultural biases.

A decent definition of culture would read as follows: Culture is an integrated system of learned patterns for behavior characteristic of the members of [a] society. The important element in this definition is that culture consists of learned patterns for behavior (Keesing, 1976). In short, it is a general [pattern] that generates behaviors but does not dictate them in detail. Thus, one can accept the [pattern] f Second Lieutenant, or teacher and interpret the cultural scripts in ways that are both individualistic and even [a way of behaving, thinking, or feeling that is peculiar to an individual or group].

However, our learned cultural patterns are often both subtle and interlocking in ways that participants fail to appreciate (Shore, 1996). This is due to the manner in which we learn our culture through a process that begins at birth (Munroe & Munroe, 1994; Williams, 1972). Obviously some of our cultural patterns are the result of conscious instruction: “Sit up Straight at the Table,” and so forth. The virtue of these elements is that we are conscious of them and can decide to accept them, reject them, or modify them. However, there are many cultural patterns that we acquire by daily interaction with others without any seeming instruction occurring. These elements can be more problematic because we are unaware that we carry them (Mayer, 1970). We can neither reflect on these elements, nor modify them. This gives them a peculiar power to affect our behavior and our beliefs.

For a quick and uncontroversial example of this power, consider what happens when you approach another person. One or both of you will stop before entering something called the intimate zone. For middle-class Americans that is a range of 18 inches best measured between bridges of two noses (Hall, 1966; Raybeck, 1991). Similarly, reflect on how uncomfortable it is to be in a packed elevator. People are forced within one another’s intimate zone and will strive mightily to avoid eye contact. At no point has anyone ever instructed us not to stand closer to another than 18 inches, but we learn this by interacting with others starting in school and continuing throughout life. Although the rule is an unconscious one, it is extremely powerful. Should you doubt this, try to consciously violate it and see what happens.

Our cultural background provides each of us with a worldview, a set of beliefs and predispositions about the nature of others, ethics, and even reality. Between cultures worldviews can differ widely, but it is also the case that some sub-cultures within a culture can produce markedly different worldviews (Osgood, May, & Miron, 1975). This is a major issue with which we must wrestle, if we wish to facilitate the educaton of our Veterans [and their transition back into civilian society in general].

For functional reasons, the organization of military structures is necessarily top-down. There are clear relations among componants and every step is taken to reduce ambiquity. This is true not only for the definition of roles within the military structure, but, despite the inevitable “fog of war” (Clausewitz, 2006), it is also true for any orders that are directed throughout the ranks. No one wishes to encounter a set of directions capable of several interpretations, nor should there be any confusion about positions of responsibility with respect to tasks assigned.

For functional reasons, the organization of military structures is necessarily top-down. There are clear relations among componants and every step is taken to reduce ambiquity. This is true not only for the definition of roles within the military structure, but, despite the inevitable “fog of war” (Clausewitz, 2006), it is also true for any orders that are directed throughout the ranks. No one wishes to encounter a set of directions capable of several interpretations, nor should there be any confusion about positions of responsibility with respect to tasks assigned.

The cultural values of the military are clear and are inculcated from the beginning: duty, honor, country. This triad, or something very like it is part of the oath that every service person takes and is reinforced in interactions with both peers and superiors. Indeed, the importance of honor among combat personnel can be traced to medieval times (Murray, 1999). The concern with country generally involves a call for patriotism. This in turn exalts bravery and, to some extent, obediance to authority. This last is literally a functional prerequisite for any military.

Unintentionally, but almost [inescapable], the military also elevates the importance of macho ethic. This is the case irrespective of gender, as women are also expected to be tough, assertive, and physically capable. Indeed, physical prowess is highly valued, partly because it may translate into good fighting skills. A corollary of these concerns is a remarkable bond between those with whom one fights. Loyalty to your buddies is an integral component of any military endeavor. It is, as many have noted, the main reason that individuals fight (Hillen, 1999).

A more problematic issue, given our concerns, is the general attitude of the military services, exempting the Marine Corps, toward education. As Murray has noted,

“Another apparent weakness in the current military culture climate, and one that certainly did not [occur] in the interwar period, is the decline of professional military education, the subject of a devastating House Armed Services Committee report of the late 1980s. To be sure, the Naval War College remains the finest institution of its kind in the world, but unfortunately the navy still resolutely refuses to [physically] send its officers to school. Elsewhere, the fact that the National Defense University seriously considered getting rid of its entire civilian faculty so that it could finance the buying of sophisticated computers suggests a general disdain for serious military education among those heading such institutions. In fact, the inclinations within the world of professional military education reflect the attitudes of both the larger military culture and society: profoundly anti-intellectual and ahistorical (1999:146-47).

To the extent that he is accurate, we must be concerned about the degree to which military organizations will be active participants in preparing veterans to enter or reenter institutions of higher education [or again transition back to civilian society].

The relationship of the military to society has been problematic, literally for thousands of years, even before Caesar first marched his armies into Rome (Clausewitz, 2006). Acknowledging that military cultures differ significantly one from the other, one must still observe that they are even more different from the society they serve. This is true not only of the United States but in the great majority of countries around the world, excepting those that are ruled by their military structures. United States society aspires to a set of liberal values enshrined in its Constitution. Military organizations, in contrast, are functionally required to emphasize a non-egalitarian, non-inclusive set of rules.

At the same time, the military is committed to a service ethic and the protection of the wider society. This is a core element of military culture and one that is seldom acknowledged by the broader society. Although generally conservative, the tight structure of military organizations can be used as force for change (Murray, 1999). It was largely through the military that both African Americans and women were able to make significant social progress. [It remains to be seen if the recent repeal of Don’t Ask Don’t Tell will do the same for gay service members.]

The fact that military personnel live in circumstances that estrange them from the wider society only exacerbates some of these differences and tensions. Negative stereotypes can abound in the absence of shared communications and experience. Military personnel can easily view the wider society as [self-indulgent to pleasure and happiness as a way of life], materialistic, and weak. At the same time, civilians can view the military as rigid, authortarian, and narrow. These opposing percepts set the stage for conflictual encounters.

The organization of [Academia] consists of administrators, faculty, and students. Administrators generally serve for a limited period of from 5 to 10 years. It is quite common for deans and even [college and university] presidents to return to the faculty after their period of service. Responsibilities for the operation of the institution are divided among several bodies including the trustees, the administration, and the faculty. The domains and prerogatives of all three bodies are often poorly defined. To further muddy the waters, there are faculty committees, student committees and joint faculty-student committees, often with an administrator in attendance.

The organization of [Academia] consists of administrators, faculty, and students. Administrators generally serve for a limited period of from 5 to 10 years. It is quite common for deans and even [college and university] presidents to return to the faculty after their period of service. Responsibilities for the operation of the institution are divided among several bodies including the trustees, the administration, and the faculty. The domains and prerogatives of all three bodies are often poorly defined. To further muddy the waters, there are faculty committees, student committees and joint faculty-student committees, often with an administrator in attendance.

The monthly business of the institution is realized at faculty meetings where changes are made to the curriculum and to aspects of community governance. Such faculty meetings are often characterized by a [array] of voices and a wide variety of positions. It is even possible for faculty to pass a vote of no confidence in the president. This action effectively terminates the individual’s presidency. Imagine anything remotely resembling this in the military.

The values and beliefs of [Academia] highlight the importance of free and unfettered inquiry. Indeed, this is the rationale behind tenure [seniority]. No one should lose their job because they espoused an unpopular position or carried out controversial research. There is suppose to be, and often is, a commitment to general equality and egalitarianism. This is sometimes violated within departments when a chair or full professor uses his or her position to disadvantage an assistant or associate professor. However, the value of egalitarianism is reflected in common academic rhetoric that emphasizes the institution as a “community of learners”.

The great majority of faculty believes that authority should be questioned and they take [positions that challenges or overturns traditional beliefs, customs, and values] regarding many social institutions. One of the benefits of [seniority] is that it allows faculty to question their own authorities and to participate actively in the governance of the educational institution. As I noted above, this can go to some extreme. Many faculty, in contrast to members of the military, enjoy ambiquity.

There are also many who disparage the macho ethic, and even some who denigrate participation in many sports. Faculty members, like most of us, are leery of those who are different. Not surprisingly, few faculty seriously engaged in sports during their youth. Many also tend to see physical competition as at odds with the life of the mind.

As was the case for the military, the relationship of [Academia] to the wider society can be problematic, but in a very different fashion. Most members of [Academia] do not have a prominent service ethic. Indeed, as suggested above, many are critical of the wider society and often quite vocal in their critiques. While some of these criticisms can be dismissed as simple [whining], many are intended to be constructive and a source of progress and improvement. However, society rarely welcomes academic criticisms. Instead, due to the rather marginal position of most academics, their commentaries are usually dismissed as the rantings of pointy-headed intellectuals.

Members of [Academia] are also somewhat removed from interaction with the wider society, though to a much lesser degree than the military. However, many faculty believe it is beneath them to reach out to the wider public. Many faculty disparage efforts to popularize research with the unfortunate consequences of marginalizing those who undertake this endeavor. Often the public lacks an understanding of how grants that enable the study of a variety of obscure subjects might benefit society at large and, in the absence of good communication, we once again encounter faculty stereotypes such as the one described above. Finally, with notable exceptions, both politically and socially members tend to be quite liberal. (These problems and many more have been very well described by Douglas Herrmann and colleagues, 2009).

THE CULTURE CLASH

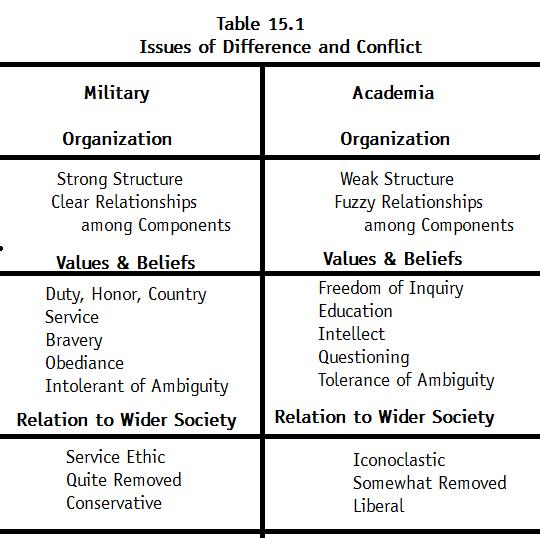

It seems obvious that even with goodwill on both sides, conflict between members of these two institutions [academia and the military] is likely. I will argue later that the difficulties I am about to describe can be reduced and perhaps even resolved. However, many differences are in direct opposition to one another [as shown in] (Table 15.1) below:

It is likely that [Veterans] who enter [Academia] will be older and have more experience than then the typical undergraduate. [Contradictory, but in fact is or may be true], the typical veteran may experience swings between self-assurance and insecurity depending on the context. In circumstances where there is respect shown for the person’s accomplishments and sacrifices, self-assurance and even a degree of social acceptance can be anticipated.

However, the educational environment will be novel and even strange [except maybe for those college students whose incentive for military service was education assistance thus already attended college before enlistment]. That can lead to uncertainty about the nature of present expectations and acceptable, even approved behavior. For instance, the better professors, and often the more popular ones, enjoy being challenged in the classroom. Disagreeing with or challenging authority may not initially be an easy undertaking for most former service [members].

It is also quite possible that veterans will harbor stereotypes of [Academia], the typical student, and professors. These can color and interfere with the nature of the educational experience.

There are a variety of other interpersonal factors that can create friction between former military personnel and other students. [Veterans] may well be resentful of those who haven’t served and done their duty. They may also find them both naïve and inexperienced. Many military [members] are likely to take a very pragmatic attitude toward their education, viewing it mainly as a means to employment, and eschewing abstractions and courses that do not seem directed toward a practical goal. To the extent that this attitude is visible to professors, they may be expected to respond unenthusiastically or even negatively.

The problems confronting healthy entering military personnel are significant, as we shall see below. The main issue is one of cultural and perceptual differences. However, many entering former service [members] will have a degree of mental trauma such as PTSD or related problems with which they must deal. Obviously, these issues complicate an already difficult situation. Finally, there are those service [members] who enter [college] with significant and visible physical trauma. In addition to managing the situational difficulties they encounter, they must also manage the attitudes and behaviors of those around them (Goffman, 1959, 1963).

The [typical non-veteran] students that the service [member] will encounter range from privileged to poor. The precise mix will depend upon the nature of the institution, but one commonality is that nearly all of these other students will be [ignorance] of military life and of the experiences it promotes. Students may be admiring or, or resentful toward, the [veteran] depending on a variety of factors such as [socio-economic] class, comportment, and even appearance. While some will be curious about the experiences of [veterans], many, perhaps most will harbor a variety of inaccurate stereotypes. It may also be anticipated that many of these will be negative. [Veterans] may be seen as unintelligent [note that Dr. Raybeck does not use the word unintellectual], unoriginal and even in favor of killing (Herrmann et al., 2009).

Most faculty and administrators are also likely to be less than wholly cognizant of the transition problems facing veterans. Many may well possess the same negative and ignorant stereotypes held by many students (Herrmann et all, 2009). The issue here, like many of the ones described above, is largely one of culture.

Many faculty view the military as a dangerous and unfortunate necessity.

Historically however, there have been significant exceptions. During World War II numerous well-known anthropologists contributed their expertise to understanding the enemy. Benedict’s flawed, yet useful and extremely influential work on the Japanese is an excellent example. Despite the liberal and academic nature of the profession, many well-known anthropologists not only served in WWII, they employed their expertise in covert activities. More than two dozen of them worked for the [Office of Strategic Services (OSS)] including such luminaries as Gregory Bateson, Carleton Coon, Cora DuBois, Felix Keesing, and George Murdock (Price, 1998).

Now, however, many anthropologists harbor reservations concerning the present participation in Iraq and Afghanistan, particularly those involving tribal relationships. [Source: Anthropolgy and the Military.]

Even those administrators and faculty members who are well disposed toward veterans may well unintentionally and insensitively estrange and discourage these new entering [or returning] students. The problem seems to involve both cultural misperceptions and a lack of adequate communication.

TOWARD A RESOLUTION

The first step to addressing the problems described above is to recognize that they exist. This is the responsibility of the [college or university] administration. They must take steps to educate their faculty and staff concerning these matters. This education should be of an experiential rather than literary nature. Nothing works better than interaction, because it increases communication and diffuses stereotypes. Communication is key to easing the entry of veterans and to making others aware of the complex nature of problems at hand.

Many entering veterans may need, and certainly are likely to benefit from, remedial training in academic skills. Educational institutions are discovering that this is also true of many of the [typical non-veteran] students. Thus, where possible, it would be desirable to place both sorts in joint classes designed to address reading, writing, and [mathematics] deficiencies.

Public forums, including veterans, students, and faculty, could be directed specifically to these problems. In addition to serving as educational vehicles for the wider community, these forums would greatly deepen mutual understanding for the participants. Other public forums such as those that address current events could also fold in veterans as well as the typical student. Finally, every educational institution has a series of joint social and educational endeavors, such as community outreach programs, where veterans could be encouraged to play a role. Indeed, given what will often be their less priviledged background, they may be extremely well suited to be helpful with the disadvantaged.

Much work clearly needs to be done on support services.

Most counseling centers are not prepared for, nor experienced with, the mental traumas that may accompany the entry of many veterans. It would also be very helpful if the educational institution were to provide facilities for physical therapy. This need not be enormously expensive as most institutions have elaborate gyms and many have excellent trainers and physical therapists. The nature of the disabilities that some veterans will have may require further training on the part of physical therapists. Educational institutions should encourage this and underwrite the cost of it. Obviously, steps should also be taken to improve physical access both to dormitories and to classrooms.

A less obvious, yet important, concern is the enforcement of social rules and norms.

This is something that administrators often do not handle well. Fear of bad publicity, lawsuits, and a series of other negative possibilities often leads administrators to deal very leniently with bad behavior. Nonetheless, virtually every campus possesses a behavior code, even though it may be poorly enforced. I am recommending that enforcement be prompt and strict. It should be obvious that this is the case whether the offender is a typical student or a veteran. Most campuses have rules about harrassment and insults, but those are typically directed to the issues of race, gender, and sexual orientation. Educational institutions need to become sensitive to the manner in which former military personnel can be mistreated and insulted.

The military itself could play a much greater [proactive] role than it presently does in preparing those who plan to leave the military and enter [Academia or Civilian Society in general].

The services could hold seminars and role-playing exercises that could offer a glimpse of some of problems that may well be encountered. At the very least, brochures or even relevant books such as Educating Veterans in the 21st Century (Herrmann et al., 2009) could be provided to veterans to help them anticipate some of the difficulties they will encounter.

Finally, the objective of successfully integrating and educating veterans in an academic environment can be greatly facilitated by better [two way] communication within the various components of the [college or university] and between the [college or university] and the military [and Department of Veterans Affairs]. At the present time, the relationship between these [three] vital institutions is more conflictual than cooperative. Each needs to be able to see the other as a complementary component of the wider society. [All] have missions to accomplish and…benefit the society at large. That they do so in very different ways should not be a cause of friction, particularly if it is realized that each need, perhaps even require, the other.

References

Clausewitz, C. V. (2006). On War (C.J.J. Graham, Trans.), London: Project Gutenburg Ebook.

Goffman, E. (1959). The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life. New York: Doubleday Anchor Books.

Goffman, E. (1963). Stigma: Notes on the Management of Spoiled Identity. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Hall, E.T. (1966). The Hidden Dimension. Garden City, NY: Doubleday Anchor.

Herrmann, D., Hopkins, C., Wilson, R.B., & Allen, B. (2009). Educating Veterans in the 21st Century. North Charleston, South Carolina: BookSurge.

Hillen, J. (1999). Must U.S. Military Culture Reform? OrbisPhiladelphia, 43(1), 43-58.

Keesing, R. (1976). Cultural Anthropology: A Contemporary Perspective. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston.

Mayer, P. (1970). Socialization: The Approach from Social Anthropology. London: Tavistock publications.

Munroe, R.L., & Munroe, R.H. (1994). Cross Cultural Human Development. Prospect Heights, IL: Waveland Press.

Murray, W. (1999). Does Military Culture Matter? OrbisPhiladephia, 43(1), 27-42.

Osgood, C.E., May, W.H., & Miron, M.S. (1975). Cross-Cultural Universals of Affective Meaning. Urbana: Univeristy of Illinois Press.

Price, D.H. (1998). Gregory Bateson and the OSS: World War II and Bateson’s Assessment of Applied Anthropology. Human Organization, Winer.

Raybeck, D. (1991). Proxemics and Privacy: Managing the Problems of Life in Confined Environments. In A.A. Harrison, Y.A. Clearwater & C.P. McKay (Eds.), From Antarctica to Outer Space: Life in Isolation and Confinement (pp 317-330). New York: Springer-Verlag.

Shore, B. (1996). Culture in Mind: Cognition, Culture, and the Problem of Meaning. Oxford University Press.

Williams, T.R. (1972). Introduction to Socialization. St. Louis: C.V. Mosby Company.

About the Author : Dr. Douglas Raybeck, Emeritus Professor Hamilton College, Founding President, College Educators for Veterans Higher Education

: Dr. Douglas Raybeck, Emeritus Professor Hamilton College, Founding President, College Educators for Veterans Higher Education

Readers are more than welcome to use the articles I’ve posted on Veterans Today, I’ve had to take a break from VT as Veterans Issues and Peace Activism Editor and staff writer due to personal medical reasons in our military family that take away too much time needed to properly express future stories or respond to readers in a timely manner.

My association with VT since its founding in 2004 has been a very rewarding experience for me.

Retired from both the Air Force and Civil Service. Went in the regular Army at 17 during Vietnam (1968), stayed in the Army Reserve to complete my eight year commitment in 1976. Served in Air Defense Artillery, and a Mechanized Infantry Division (4MID) at Fort Carson, Co. Used the GI Bill to go to college, worked full time at the VA, and non-scholarship Air Force 2-Year ROTC program for prior service military. Commissioned in the Air Force in 1977. Served as a Military Intelligence Officer from 1977 to 1994. Upon retirement I entered retail drugstore management training with Safeway Drugs Stores in California. Retail Sales Management was not my cup of tea, so I applied my former U.S. Civil Service status with the VA to get my foot in the door at the Justice Department, and later Department of the Navy retiring with disability from the Civil Service in 2000.

I’ve been with Veterans Today since the site originated. I’m now on the Editorial Board. I was also on the Editorial Board of Our Troops News Ladder another progressive leaning Veterans and Military Family news clearing house.

I remain married for over 45 years. I am both a Vietnam Era and Gulf War Veteran. I served on Okinawa and Fort Carson, Colorado during Vietnam and in the Office of the Air Force Inspector General at Norton AFB, CA during Desert Storm. I retired from the Air Force in 1994 having worked on the Air Staff and Defense Intelligence Agency at the Pentagon.

ATTENTION READERS

We See The World From All Sides and Want YOU To Be Fully InformedIn fact, intentional disinformation is a disgraceful scourge in media today. So to assuage any possible errant incorrect information posted herein, we strongly encourage you to seek corroboration from other non-VT sources before forming an educated opinion.

About VT - Policies & Disclosures - Comment Policy