by Anthony Hall

From South Africa to Gaza to British Columbia and Alberta:

Crime Wave Directed at the Elimination of Indigenous people

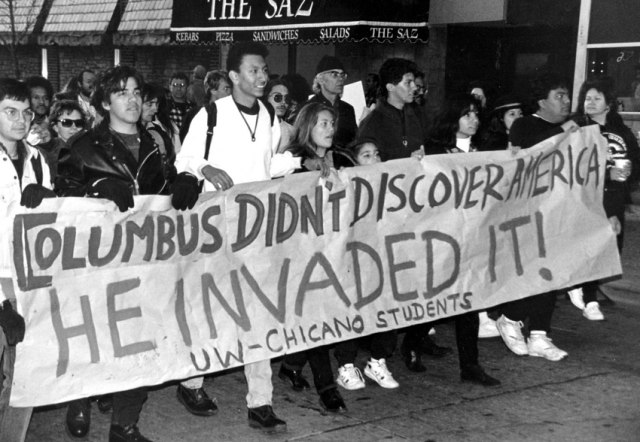

Many aspects of the world we are inheriting from our ancestors and are passing along to posterity go back to the trajectory of colonial history initiated in 1492 with Christopher Columbus’s initial trans-Atlantic voyage. The seizure by European powers of imperial control in the Americas initiated a process that continues to divide humanity. On one side of the divide are those on the delivering end of a colonizing process that never really ended. On the imploding side of colonization’s expansionary frontier are the Indigenous peoples. They are on the receiving end of an ongoing saga of dispossession, disempowerment and marginalization.

Proof of the continuing nature of this oppressive process is all too evident in the statistics of suicide, domestic violence, incarceration, unemployment, poverty, addictions and the like. These stats continue to demonstrate, unfortunately, that Canada is not a country of decency and equity where human rights are respected and protected from wholesale violation. Those referred to in Canada’s highest constitutional law as the “Aboriginal peoples of Canada,” as “Indians, Inuit and Metis,” are overwhelmingly overrepresented on the negative side of virtually every major index of morbidity, illness, and socioeconomic status.

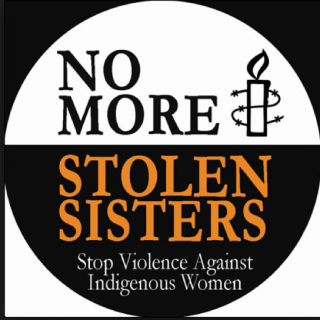

The Aboriginal peoples of Canada are suffering because of a centuries-old crime wave directed in their direction. Often these crimes are sanctioned or actually committed by governments and police forces in Canada, in its ten provinces and in its three federal territories. The predatory incursions currently suffered by the First Nations are epitomized by the 1,500 or so missing, murdered and traded Aboriginal women and girls that Canada’s racist criminal justice system cannot account for.

police forces in Canada, in its ten provinces and in its three federal territories. The predatory incursions currently suffered by the First Nations are epitomized by the 1,500 or so missing, murdered and traded Aboriginal women and girls that Canada’s racist criminal justice system cannot account for.

There is a growing swell of political pressure developing in Canada calling for a federal investigation into the phenomenon of missing, murdered and traded Aboriginal women and girls. This groundswell now extends even to many of Canada’s provincial premiers. Those who introduced the call for an investigation are closely connected to Idle No More, a very important movement whose most erudite activists have been doggedly exposing the links connecting the repression of Indigenous peoples in Canada and Palestine/Israel. This comparison is epitomized by the anti-Aboriginal policies of Stephen Harper, Canada’s neocon Prime Minister who has outdone even US politicians in displaying utter subservience to the anti-Palestinian dictates of Benjamin Netanyahu and his Likudnik obsessions. The anti-Palestinian blood lust of many citizens of the Israeli state was put on full international display during the recent Israeli invasion of Gaza.

Rather than authorize a federal investigation into the missing, murdered and traded Aboriginal women in Canada, Harper has chosen to play to the well-known bigotry of his most loyal political base, a constituency that historically maintained strong political ties with the White minority regime that ruled South Africa until the early 1990s. Accordingly, the Aboriginal policies of the Harper government in Canada continue in the present many of the same patterns of repressive treatment of Indigenous peoples that once made such close partners of the governments of the Jewish state of Israel and the White-supremacist state of South Africa.

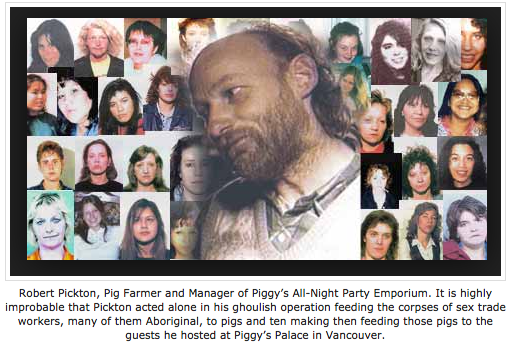

Ground zero of the saga of missing and murdered Aboriginal women and girls in Canada is the dual pig farm and party emporium in the Greater Vancouver area known as Piggy’s Palace. Scores of sex trade workers, many of them Aboriginal, met their demise at this strange establishment where the corpses of sex trade workers were fed to drug-addicted pigs. Some of the pigs were fed in turn to clients who frequented the weird entertainment facilities. Many questions continue to swirl around Piggy’s Palace, which was situated nearby a Hell’s Angels residence. Between 1997 and 2002 Vancouver police, including local RCMP, were given much evidence that homicides of sex trade workers were regularly taking place at the pig farmer/ party emporium. Some of the families of the victims conducted their own investigations in the absence of any proactive intervention on the part of police. In spite of all the evidence brought forward to the appropriate officials, nothing of substance happened year after year as the numbers of disappeared sex trade workers mounted.

Robert Pickton, the proprietor of Piggy’s Palace, was eventually convicted of several killings. But even to this day it seems investigators are holding back from dealing with the whole sordid story of the crime spree they had so long ignored altogether. The Crown’s contention that the sordid mess could be blamed in its entirety on a single individual continues to raise questions. Indeed, the investigation conducted by Wally Opel, a former Attorney-General in an obvious conflict of interest, shows many signs of being a classic cover-up to protect the guilty. While Pickton has been the focus of the Crown’s odious “sole-gunman” theory concerning what took place at Piggy’s Palace, it is highly probable that the criminal activities extend more broadly, possibly even to some prominent Vancouverites with close ties to the criminal justice system.

The scandal keeps festering in a province where there have long been rumors of pedophilia rings thriving on the trade of Aboriginal children in places like the posh Vancouver Club, a watering hole for the rich where in 2011 the book-promoting Dick Cheney was engulfed by citizen jurists demanding that the primary 9/11 suspect be arrested for war crimes. Other reports have circulated that drug cartels in BC use coastal Indian reserves for landing sites in a many-faceted trade including the selling of stolen and drugged Aboriginal youths into Asian sex emporiums. These narratives circulate in a milieu where there has been a series of revelations showing the involvement judges and RCMP officers in particular cases of predatory treatment of Aboriginal women, girls and boys.

Splitting The Sky versus Neocons George Bush, Stephen Harper, and Benjamin Netanyahu

Under Prime Minister Stephen Harper the government of Canada eschews responsibility to protect even the very persons of the Aboriginal peoples of Canada let alone their constitutionally recognized titles to a significant portion of the lands and waters of northern North America. Indeed, the Harper government’s effort to transform Canada into a Petrotyranny is becoming a catalytic force renewing many of North America’s most unseemly heritages of Aboriginal dispossession, repression and efforts of elimination. Among Harper’s key backers and helpers are the reprehensible Koch Brothers of Tea Party notoriety. The Koch Brothers have purchased extensive rights to the Alberta Tar Sands. They have been leading the way in trying to connect the land locked source of Alberta’s Swamp Bitumen to their processing facilities in, for instance, the Gulf of Mexico through the Keystone XL pipeline.

Harper’s promotion of the Koch Brothers’ agenda for the toxic Alberta Tar Sands and the rest of Canada is part of a larger complex of policies that extends to helping the government of Israel implement Oded Yinon’s strategy of dominating the Middle East through instigating divide-and-conquer techniques. The Yinon plan plan involves the destabilization of the old puppet dictatorships in Arabia that since the Second World War have pumped a steady flow of oil from the region. Harper’s plan is that Canada will supply an accelerating stream of fossil fuels to replace declining oil supplies from a Middle East plunged into hellish maelstroms of civil war to serve the Israeli government’s plans for expansion and domination.

The Harper government has given cover to this scheme by dubbing Canada’s dirty oil “Ethical Oil.” The term originated with Ezra Levant, one of the most high-profile agents involved in the task of bringing the Calgary-based Oilpatch of Canada into line with Israeli policies and priorities. The Calgary-based Oilpatch is sometimes dubbed Texas North because of its close ties to the state that has been a key base of operations for the Bush family, the bin Laden clan etc etc.

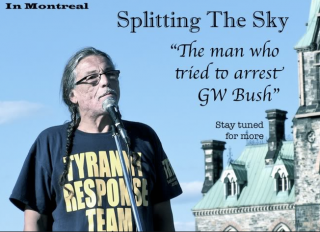

Some of these patterns began to come to light in the case of Splitting The Sky versus George W. Bush. The illustrious Mohawk activist and Attica Brother attempted in 2009 a citizen’s arrest in Calgary of the former US president during his first public presentation as a private citizen. The resulting trial, in which former US Attorney General Ramsay Clark testified, was largely covered up by Canada’s notoriously gate-kept media. Last year Splitting The Sky met a violent death at age 62 under murky circumstance in small-town British Columbia just as controversies over the Harper government’s effort to fast track the building of pipelines through Canada’s westernmost province began to bubble up to the surface.

Some of these patterns began to come to light in the case of Splitting The Sky versus George W. Bush. The illustrious Mohawk activist and Attica Brother attempted in 2009 a citizen’s arrest in Calgary of the former US president during his first public presentation as a private citizen. The resulting trial, in which former US Attorney General Ramsay Clark testified, was largely covered up by Canada’s notoriously gate-kept media. Last year Splitting The Sky met a violent death at age 62 under murky circumstance in small-town British Columbia just as controversies over the Harper government’s effort to fast track the building of pipelines through Canada’s westernmost province began to bubble up to the surface.

The questions keep mounting, therefore, about what is going on in Canada, a country hosting a disproportionate number of Aboriginal people in federal penitentiaries and provincial jails. The jailing of Aboriginal people in Canada involves a much larger percentage of the prison population than the proportion of Black inmates currently warehoused in the notorious privatized penal colonies internal to the United States

In order to understand the full depth of the crime wave aimed at Indigenous peoples in Canada it is necessary to turn to the constitutional history of how the legal protections for Aboriginal and treaty rights came to become entrenched. Much of this history unfolded in the period before the United States emerged from a secessionist movement in British North America. Indeed, US and Canadian history converges and emerges from conflicting reactions to a British imperial constitutional instrument known as the Royal Proclamation of 1763.

Much of the crime wave currently corroding Canada’s image as a friend of human rights and the rule of law is occurring in court where legal instruments such as the Royal Proclamation of 1763 are subject to contestation. In the course of many trials the federal government’s lawyers in Canada are systematically violating basic constitutional principles to advance the political agendas of the main predators at the forefront of the wholesale ethnic cleansing currently underway on the resource-extraction frontiers of Northern North America.

This crime wave systematically violates Canada’s highest law. Canada can claim to be a country with constitution that proclaims that “the existing Aboriginal and treaty rights of the Aboriginal peoples of Canada are to be recognized and affirmed.” But that declaration is a lie, nothing more than a smoke screen to obscure the truth from the international community that the Canadian government is itself the primary predator in the assault against the Aboriginal and treaty rights of First Nations in Canada.

When it comes to testing the meaning of this constitutional law, lawyers acting for the Canadian government consistently mount arguments whose effect is to deny and negate rather than recognize and affirm the existence of Aboriginal and treaty rights. The proof of the unbroken urge to push Indigenous peoples aside in the name of a very distorted and ethnocentric vision of progress lies in the grotesque rate of Aboriginal over-representation in the jails, in the police reports, in the hordes of the homeless blighting Canada’s major urban centres, in the unemployment lines, in the morgues, and in the roll call of the 1,500 or so missing and murdered and traded Aboriginal women and girls whose disappearance cannot be explained by the criminal justice system.

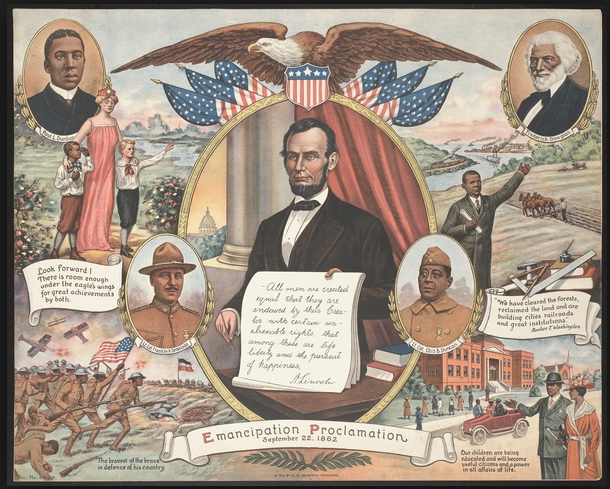

The Emancipation Proclamation of 1863 and the Royal Proclamation of 1763

Indigenous peoples are not the only groups to have felt the whip of injustice in a color-coded trajectory of colonization that continues yet. Many Indigenous peoples continue to suffer forms of oppression emanating from the same taproot of injustice once visited on Black slaves. The slave trade, which reduced human beings to property, brought violently uprooted Africans from their ancestral lands and transported them against their will to the Americas where they were sold into regimes of forced labor, mostly on huge agricultural plantations.

Narratives of the trans-Atlantic slave trade often extend to accounts of the freeing of the slaves. In the United States this history lesson often culminates in the story of how President Abraham Lincoln ended slavery in the course of the American Civil War. President Lincoln changed the course of history with his Gettysburg Address followed by the Emancipation Proclamation of 1862.

Generally speaking the history of the dispossession and subjugation of Indigenous peoples does not receive the same kind of attention as the story of slavery in America because there has never been a significant reversal to the centuries-old theft of land, resources and life chances from First Nations peoples. There is seemingly no equivalent for Indigenous peoples of the Emancipation Proclamation to give the story of their treatment some kind of happy ending, however limited, provisional or contrived.

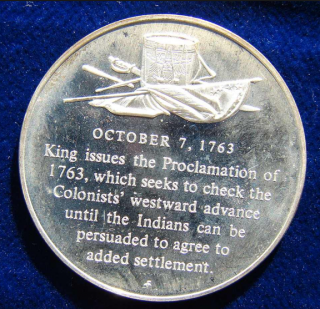

In the northern part of North America, however, we have it in our power to bring out from obscurity a constitutional instrument somewhat like the Emancipation Proclamation of 1863. Exactly 100 years before President Lincoln set the slaves free, King George III instituted a colonial law that would have afforded Indigenous peoples some protections to fend off the land theft and vigilante violence that had long characterized the frontier regions of Anglo-America.

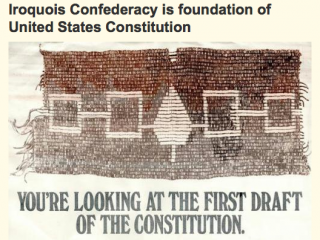

King George drew on the advice of Sir William Johnson who had long represented the British imperial government in the old Covenant Chain of Crown treaty diplomacy with the Six Nations Iroquois. This Covenant Chain drew, in turn, on the world famous indigenous constitution of the Six Nations Longhouse Confederacy. In the Mohawk tongue this celebrated Confederacy was known as the League of the Haudonosaunee. In 1987 the US Congress passed a statute acknowledging that the US federal system is to some extent modeled on this Longhouse League. This League, whose original seat of government was under the Great White Pine of Peace in Onondaga territory of what is now New York state, has attracted the rapt attention of many prominent social theorists including Benjamin Franklin and Karl Marx.

Chain drew, in turn, on the world famous indigenous constitution of the Six Nations Longhouse Confederacy. In the Mohawk tongue this celebrated Confederacy was known as the League of the Haudonosaunee. In 1987 the US Congress passed a statute acknowledging that the US federal system is to some extent modeled on this Longhouse League. This League, whose original seat of government was under the Great White Pine of Peace in Onondaga territory of what is now New York state, has attracted the rapt attention of many prominent social theorists including Benjamin Franklin and Karl Marx.

An experienced participant in the decision-making rituals of the Longhouse League and the British King’s primary polisher of the metaphorical silver links in the treaty diplomacy of the Covenant Chain, Sir William Johnson brought his depth of experience to the process of drafting of the Royal Proclamation of 1763. The Indian provisions in the Royal Proclamation were aimed at persuading Indian people to join the British Empire on the understanding that there would be constitutional protections for their persons, their families, their nations and confederacies of nations as well as for their titles to their ancestral lands and waters.

Envisaging the negotiations of future Crown-Aboriginal treaties in a well regulated and orderly westward expansion of Euro-Americans, King George III incorporated the fur-trade territory of French-Aboriginal Canada into British North America with this Royal Proclamation. Another feature of this constitutional instrument was its creation of the new British colony of Quebec including provisions to accommodate the Roman-Catholic attributes of the new jurisdiction’s French-speaking majority, the former colonists of New France.

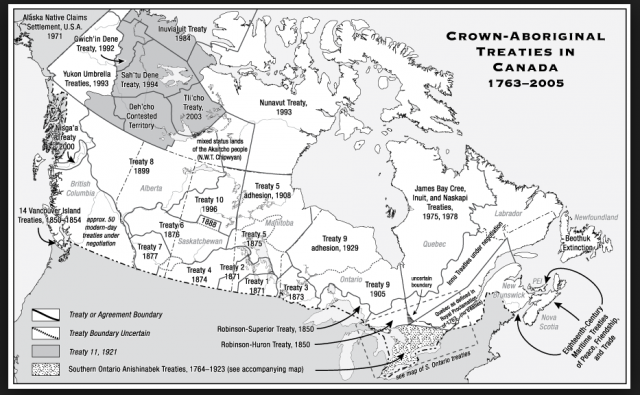

The Royal Proclamation initiated a process of negotiating Crown-Aboriginal treaties with First Nations that continues in British Columbia to this day. Canada’s Constitution Act, 1982 specifically acknowledges the Royal Proclamation. Unfortunately, however, the recognition and affirmation of existing Aboriginal and treaty rights in the 1982 document was not interpreted in the courts in a way that renewed the emancipating possibilities of the Royal Proclamation. So far this possibility has been sabotaged by the cynical juridical tricks of high-priced lawyers acting through government on behalf the most rich and powerful corporate interests in Canada.

King George III Prohibits the Expansion of Euro-American Settlements in North America Through Conquest or Vigilante Violence

The Royal Proclamation of 1763 was and is integral to a legal and moral tradition concerning the transfer of lands and resources to non-Indian individuals and corporations based on principles of the need for mutual consent. This prohibition on the incursions of conquest to expand the area of Euro-American settlements in North America is a landmark of constitutional history and international law. Too often the doctrine of “discovery” or the doctrine that the laws of Christian imperial powers immediately preempt the laws of non-Christian polities have been deployed to give the veneer of law to the genocidal displacement and elimination of Indigenous peoples. That process continues yet, often in the name of a very specious geopolitical monstrosity known as the Global War on Terror.

The Royal Proclamation of 1763 was and is integral to a legal and moral tradition concerning the transfer of lands and resources to non-Indian individuals and corporations based on principles of the need for mutual consent. This prohibition on the incursions of conquest to expand the area of Euro-American settlements in North America is a landmark of constitutional history and international law. Too often the doctrine of “discovery” or the doctrine that the laws of Christian imperial powers immediately preempt the laws of non-Christian polities have been deployed to give the veneer of law to the genocidal displacement and elimination of Indigenous peoples. That process continues yet, often in the name of a very specious geopolitical monstrosity known as the Global War on Terror.

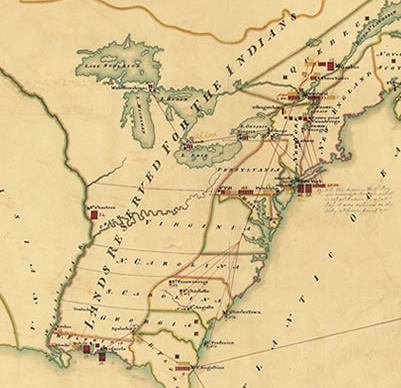

The Royal Proclamation was the chosen instrument whereby the British imperial government of King George III incorporated Canada into Britain’s thirteen Anglo-American colonies after the Seven Years’ War. It was an effort to incorporate the peoples of French-Aboriginal Canada into British North America on the basis of law and consent rather than coercion. A vital part of this proclamation—with tremendous significance for today’s Turtle Island—is its recognition of an enormous Indian reserve. This reserve extended throughout the eastern half of the Mississippi Valley and north of the Great Lakes up to the beginning of the arctic watershed. These were “lands reserved to the Indians for their hunting grounds.”

Here are two excerpts from the Proclamation that acknowledge some form of Aboriginal title to these unceded territories:

And whereas it is just and reasonable, and essential to our Interest, and the Security of our Colonies, that the several Nations or Tribes of Indians with whom We are connected, and who live under our Protection, should not be molested or disturbed in the Possession of such Parts of Our Dominions and Territories as, not having been ceded to or purchased by Us, are reserved to them, or any of them, as their Hunting Grounds.

And We do further strictly enjoin and require all Persons whatever who have either willfully or inadvertently seated themselves upon any Lands within the Countries above described or upon any other Lands which, not having been ceded to or purchased by Us, are still reserved to the said Indians as aforesaid, forthwith to remove themselves from such Settlements.

In describing these “lands reserved to the Indians,” the British monarch and his advisers lodged a very consequential phrase into the origins of British imperial Canada establishing the basis of many constitutional controversies to come. The divergent interpretations of the Royal Proclamation—the document forming Canada’s constitutional foundation—would be tested, for instance, in the 1880s when the government of Ontario took the government of Canada to court in the notorious case St. Catherine’s Milling v. The Queen (the province argued that Native peoples had rights only to those small “Indian reserve lands” that they currently occupied, not to their traditional territories).

Extending the Need for Consent, the Core Principle of Democracy, to the Indigenous Peoples

The drafters of the Royal Proclamation envisaged a gradual and orderly process for the westward expansion of Euro-American settlers into the vast Indian reserve created by the British imperial government. To ensure the orderly conduct of westward expansion, the Crown stipulated,

“If at any Time any of the Said Indians should be inclined to dispose of the said Lands, the same shall be Purchased only for Us, in our Name, at some public Meeting or Assembly of the said Indians.”

A key to unlocking the importance of this provision in the Royal Proclamation lies in its reference to the inclination of Indians to change the terms of their legal relationship to their ancestral lands. The British imperial government thereby embedded in its own constitution the need to obtain Indian consent for the westward expansion of Euro-American settlement. This historic innovation gave Indigenous peoples the prospect of exercising some considerable bargaining power in helping to chart the future of British North America.

The Royal Proclamation of 1763 acknowledges the right of First Nations to negotiate places of security for themselves and for their own Aboriginal governments in the changing environment of ongoing colonization. A balancing corrective was thereby injected into the process of colonial expansion which, from its inception, has been overwhelmingly hostile to the right, titles, prerogatives and interests of the Indigenous peoples.

The main problem then no less than the main problem now, however, is that that the democratic principles of the Royal Proclamation are only as good as the political will to enforce them. Similarly, Crown-Aboriginal treaties are pretty much farces facilitating legalized land theft unless their principles are enforced by police and subjected to interpretations that keep pace with the evolving political economy of Canada.

In order to be viable instruments of Canadian fairness and democracy, Crown-Aboriginal treaties must be seen as living agreements whose terms must constantly be re-considered in light of the changing circumstances of a world in constant motion. Thus Crown-Aboriginal treaties must be seen as being more like a verb than a noun, more like a processes for negotiating and re-negotiating the terms of living relationships than like a particular category of yellowing documents gathering dust in the remote vaults of government archives.

Like the promise of the Emancipation Proclamation, the full promise of the Royal Proclamation was never fully realized as evidenced most clearly be the disproportionate representation of Blacks and First Nations peoples in the bulging and overcrowded jails of North America. Nevertheless the Royal Proclamation like the Emancipation Proclamation embodies ideas that can inspire us yet.

The requirement to secure Indian consent as a condition for the expansion of Euro-American settlements and corporate resource extraction favored the rule of law over the rule of force, and the rule of self-determination over the rule of arbitrary command. This innovation, therefore, could have represented a substantial step away from the inequitable and unconscionable division of humanity into rights-bearing citizens and those considered too inferior for a democratic say in making their own history according to their own estimation of rights, interests, and priorities.

self-determination over the rule of arbitrary command. This innovation, therefore, could have represented a substantial step away from the inequitable and unconscionable division of humanity into rights-bearing citizens and those considered too inferior for a democratic say in making their own history according to their own estimation of rights, interests, and priorities.

The Indian provisions of the Royal Proclamation introduced a whole new dynamic into the constitutional makeup of British North America. However limited and imperfect, the King’s recognition that Indigenous peoples have the inherent human right to a say in determining their own destinies established a fundamental principle of international law that has yet to be fully embraced and applied even throughout Canada, let alone in larger theaters of global geopolitics.

To this very day, the need to obtain Indian consent is being expressed in the contemporary negotiation of Crown-Aboriginal treaties in Canada. This process is most elaborate and intense in British Columbia, Canada’s westernmost province. The current treaty-making negotiations in that territory are based on the cumulative efforts of activists, some of them Christian missionaries, who over generations politicized the failure of Crown officials to recognize Indian title in exploiting the abundant resources of the land and waters comprising Canada’s part of the Pacific Rim.

With Thomas Berger as their lawyer, the Nisga’a Nation succeeded in 1973 in getting an answer from the Supreme Court of Canada on the Indian title question. The case brought forward by Berger was in its early stages financed by the Anglican Church of Canada. In the judges’ ambivalent ruling on the Nisga’a case the Court split three to three on whether the claim to land was still valid. The seventh judge had voted against the Nisga’a on a procedural point.

Building on the ruling in the Nisga’a case the James Bay and Northern Quebec Agreement resuscitated the tradition of negotiating Crown-Aboriginal treaties in the constitutional tradition of the Royal Proclamation of 1763. That tradition had fallen dormant since 1929 when an adhesion to Treaty 9 had been negotiated at Big Trout Lake in arctic watershed of northern Ontario.

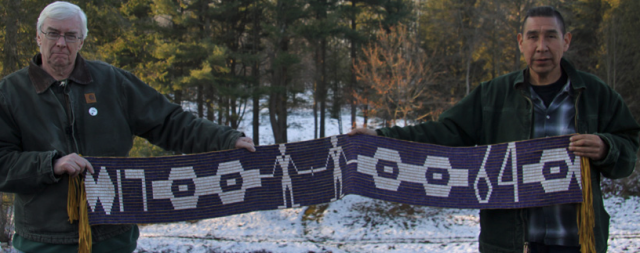

The Royal Proclamation in the Founding and Defense of British Imperial Canada

The principles of the Royal Proclamation were brought forward to the members of the Indian Confederacy of Canada at an assembly which took place at Niagara Falls in the summer of 1764. At this assembly Sir William Johnson represented the British imperial government. Following the protocol of treaty negotiations then practiced in the Indian Country of northeastern North America, Sir William presented a wampum belt whose pictorial representations outline that the King intended to protect his Indian allies in the interior of North America from the land hunger of the local settler population. The wampum belt was discussed in a very elaborate exchange embodying the nation-to-nation, sovereign-to-sovereign essence of a transaction giving birth to principles that were meant to last for as long as the sun shines, the grass grows, and the waters flow.

The Aboriginal embrace of the Royal Proclamation is evidenced by the fact that many Indian groups, but especially Sir William Johnson’s extended Mohawk family led by Molly Brant and her younger brother Captain Joseph Brant, fought on the side of the British imperial government in the American Revolution. This Crown-Aboriginal alliance culminated with Tecumseh’s mobilization of about 12,000 Indian soldiers in the War of 1812.

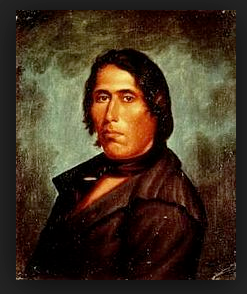

In the era leading up to the War of 1812 the principles of the Royal Proclamation had been built upon to support the geopolitical vision embraced in some imperial and Aboriginal circles of an Aboriginal Dominion with fixed boundaries along the Ohio River. The most visionary proponent of this concept was Tecumseh himself, the Shawnee sage, law giver, and General who traveled extensively in North America advocating the necessity of a broadly-based Indian Confederacy. Such a confederacy was needed, he argued, to gain standing at the high tables of international diplomacy where the so-called “White Nations” regularly carved up and apportioned sovereign authority over colonized portions of the planet.

The idea of a sovereign Aboriginal Dominion within British North America was not achieved. But in attempting to realize this goal the mobilized military forces of Tecumseh’s Indian Confederacy did succeed in defending British imperial Canada from annexation by the United States. If the Aboriginal army of the Indian Confederacy had not opposed the invading forces of the United States, Canada would today be under the Stars and Stripes because British regular forces were not in place to defend the frontier regions of what remained of British North America.

British regular forces were tied down in Europe in the war with the French imperial forces of Napoleon Bonaparte. The Aboriginal defense of Canada led by Tecumseh, who was martryed in the course of the conflict, embodies the most serious military check in the entire violent history of US westward expansion.

This history of westward colonization by US empire builders was interspersed with many dozens of small Indian wars. Even the Indian defeat of General George Armstrong Custer’s Seventh Cavalry in the Battle of Little Bighorn does not come close to the scale of the Indian Confederacy’s organized military opposition to US westward expansion in the course of the War of 1812. The most important victory of Tecumseh’s forces resulted in the US surrender of Detroit to Great Britain.

The Royal Proclamation in the Founding of the United States of America

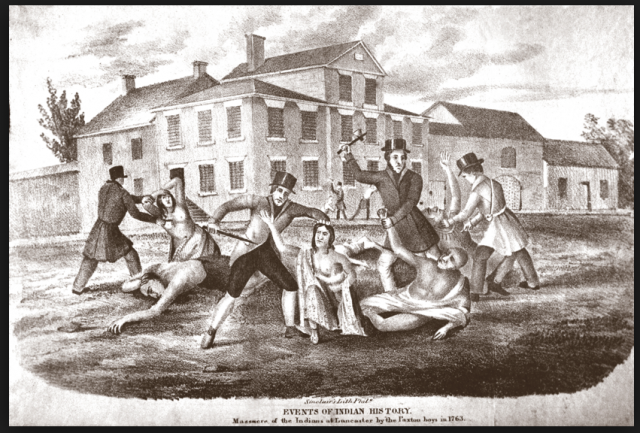

The Royal Proclamation was considered an abomination by many Anglo-American frontiersmen. In the frontier region of Pennsylvania, for instance, many Scots-Irish Presbyterians considered it their God-given mission to settle land as squatters, an imagined right they believed had been confirmed by the British victory in the French and Indian War. In the concluding phase of this conflict an Indian group gathered in the spring of 1763 around the Ottawa law-giver Pontiac.

With Pontiac’s guidance this Indian Confederacy had mounted one more military stand to demonstrate to the British that although the French had been defeated, the Indian nations in North America’s interior remained a viable military force capable of defending themselves and their ancestral lands. Tecumseh made it very clear that he considered Pontiac as one of the main sources of his strategy for the sovereign defense of the Aboriginal peoples of Canada from the genocidal campaigns of US westward expansion.

News in Great Britain of the effectiveness of Pontiac’s stand became an influential factor in the imperial government’s drafting of the Royal Proclamation issued on October 7, 1763. When news of the Royal Proclamation reached the backwoods of Pennsylvania a number of Scots-Irish frontiersmen went on a killing spree directed at the murder even of Christian pacifist Indians slaughtered en masse in the Conestoga massacre. This group of vigilante killers became known as the Paxton Boys. Some of their members would become important military officers in the Continental Army that provided the seed of the US Armed Forces once placed under the Command of General George Washington.

The Paxton Boys saw their slaughter of Indians as the basis of a political statement directed not only at the British imperial government but at the Pennsylvania Quakers who often were advocates of friendly relations with the Indians through the negotiation of treaties with them. Sir William Johnson contribution to the process of drafting the Royal Proclamation of 1763 was to some degree informed by what he had learned from pacifist Quakers including Israel Pemberton, the so-called King of the Quakers.

Thomas Jefferson clearly gave voice to the anti-Royal Proclamation position of the Paxton Boys and others of their ilk. As the principle author of the original draft of the American Declaration of Independence and as the third US president between 1801 and 1809, Jefferson wielded much influence over how the United States was founded and how it became a transcontinental power. While the Declaration of Independence begins with some ringing articulations of timeless and universal truths about human equality and the ideals of liberty, much of the document is constructed as a indictment of the alleged tyranny of King George. These provisions are meant to provide justification for taking up arms against British imperial forces in North America, including those charged to protect the lands reserved to the Indians as their hunting grounds.

the third US president between 1801 and 1809, Jefferson wielded much influence over how the United States was founded and how it became a transcontinental power. While the Declaration of Independence begins with some ringing articulations of timeless and universal truths about human equality and the ideals of liberty, much of the document is constructed as a indictment of the alleged tyranny of King George. These provisions are meant to provide justification for taking up arms against British imperial forces in North America, including those charged to protect the lands reserved to the Indians as their hunting grounds.

It is instructive to compare the wording of the Indian provisions in the Royal Proclamation of 1763 with the Indian provisions of the American Declaration of Independence. The response of the founders of the United States to wording of the Royal Proclamation reads as follows:

He [King George III] has excited domestic insurrections amongst us, and has endeavored to bring on the inhabitants of our frontiers, the merciless Indian Savages, whose known rule of warfare, is an undistinguished destruction of all ages, sexes and conditions.

The United States was thus founded on the explicit criminalization of those Indigenous peoples inhabiting the very land that were slated to become the primal capital of the fledgling White settler state. This federal entity did not incorporate Black slaves or First Nations as rights-bearing citizens of the new republic. What had King George done to justify the perception that he had “brought on” those racially profiled as “merciless Indian savages?”

The King’s supposed crime was to have attempted some accommodation of the most basic human rights of Indigenous peoples in the Royal Proclamation of 1763. The imperial government had attempted to outlaw unilateral displacement and dispossession of the First Nations. The imperial government had introduced the principle that the expansion of Euro-American settlements could not take place without Indian consent.

The King’s supposed crime was to have attempted some accommodation of the most basic human rights of Indigenous peoples in the Royal Proclamation of 1763. The imperial government had attempted to outlaw unilateral displacement and dispossession of the First Nations. The imperial government had introduced the principle that the expansion of Euro-American settlements could not take place without Indian consent.

After the Treaty of Paris in 1783 the US government moved to replicate in the North West Ordinance some aspects of the Royal Proclamation in the new republic’s basic governmental structures. By vesting the power to make treaties of peace with, or to conduct of wars of aggression on, the Indigenous peoples on the western frontiers of US expansion, the architects of the system for accelerated the transformation of the American earth into property. They did so in a way that made sure that the central government of the federal state took over the imperial functions formerly performed by Great Britain.

The US government made about 400 treaties with Indian peoples over the first decades of its existence. The terms of every one of these Indians treaties has been notorious violated by the US government. Then in 1871 Congress outlawed the making of further treaties with Indigenous peoples within the territorial outlines of the United States. The making of treaties, the US law makers argued, advanced the fiction that Indian nations were sovereign entities in international law.

The decision to end treaty negotiations meant that that the US government’s claim to sovereign jurisdiction in those parts of the country not covered by treaties rested on doctrines of conquest, the very doctrine that the Royal Proclamation of 1763 was created to preempt. This US dependence on the doctrine of conquest was confirmed in the ruling in 1955 of its Supreme Court in the case of Hee-Hit Ton Indians versus the United States. The judges decided that the US claim to sovereignty in Alaska went back to the imagined conquest of the Indigenous peoples.

The timing is significant of the US government’s legislated abandonment of further treaty negotiations with Indigenous peoples. In 1871 that US federal authority had finally emerged as the indisputable winner in the contest with the states rights movement that had supported the institution of slavery in the American south. This contest had culminated in the federal victory in the American Civil War. Having established its imperial predominance in the federal balance of power, the US central government no longer needed to demonstrates its superior authority over state governments by exercising federal power to make treaties with First Nations.

Interestingly the US government abandoned treaty making with Indigenous peoples just as the government of the new Dominion of Canada embarked in 1871 on a new round of Crown-Aboriginal treaty negotiations in the vast swath of northern territories recently acquired through purchase from the Hudson’s Bay Company in preparation for the building of the Canadian Pacific Railway. These agreements are generally described as the numbered treaties. Although a small skirmish did break out in 1885, Canada by an large opted to renew the constitutional principles of the Royal Proclamation of 1763 rather than to conduct Indian wars with the Indigenous peoples of western Canada.

The preemption of the Constitutional Heritage of the Royal Proclamation by the Indian Act

The tradition of law encapsulated in the Parliament of Canada’s Indian Acts have run against the principles of law invested in the constitution heritage of the Royal Proclamation of 1763, the terms of about 90 Crown-Aboriginal treaties in Canada, and the provision in section 35 of Canada’s Constitution Act, 1982 that “the existing Aboriginal and treaty rights of the Aboriginal peoples of Canada are hereby recognized and affirmed.” The basic thrust of the Indian Act was to transform the Crown’s Indian allies into child-like wards of the federal state. As wards of the federal government registered Indian were denied the right to vote or run in federal or provincial elections, to sign valid contracts, or to go to court to seek remedies for grievances including the theft of land and resources.

The first Indian Act enacted in 1857 in the province of Canada was telling entitled an Act for the Gradual Civilization of the Indian Tribes in Canada. The passage of this legislation signaled that the local White settler government was taking over jurisdiction from Great Britain for the conduct of so-called Indian Affairs. The Indian peoples who were made subject to this transfer of power were not consulted. In fact their political leadership organized a large assembly on the Six Nations reserve in Canada West to protest this transfer of power over their lives and over their remaining Aboriginal lands without their consent, indeed in the face of their explicitly-stated opposition.

The Royal Proclamation’s requirement that Indian consent must be obtained for major transformations in the tenure of their ancestral lands has been violated again and again with impunity. Indian consent, for instance, was not obtained for the division in 1791 of Quebec into Upper and Lower Canada, for the unification in 1841 of Upper and Lower Canada into the Province of the United Canadas, for the transfer of power from Great Britain to its settler colonies in the name of so-called responsible government, for the Confederation of Ontario, Quebec, Nova Scotia and New Brunswick as the Dominion Canada in British North American Act of 1867, for the transfer of title over Rupert’s Land and the Northwest Territories from the Hudson’s Bay Company to the Dominion of Canada in 1869-70, for the addition of British Columbia to Canada in 1871, and for the addition of Prince Edward Island, Newfoundland and the arctic islands to Canada.

The Indian Act system makes registered Indians subject to the power of the Minister of Indian Affairs, a position filled by the Prime Minister from a pool of elected MPs representing the dominant political party. Accordingly, this Minister of Indian Affairs is not selected by the First Nations nor is this Minister formally accountable to registered Indians in any way. While registered Indians subject to the Indian Act have acquired some of the rights and responsibilities of Canadian citizenship since the 1960s, the Indian Act still is directed to the assimilation of Indian peoples and Indian reserves.

The Indian Act system’s goals, for instance, still include the municipalization of Indian reserves, the privatization of Indian lands, and the termination of First Nations as distinct societies with an inherent right to take part directly in international relations through the medium of international law including the negotiation of international treaties. In this sense the Indian Act runs against the recognition and affirmation of existing Aboriginal and treaty rights and is thus unconstitutional.

The Indian Act makes a mockery of the principles espoused by King George III in the Royal Proclamation of 1763 and the trajectory of Crown-Aboriginal treaties that flow from it. In Canada, Aboriginal rights have historically been recognized and affirmed through the negotiation of treaties. The time has come to implement these treaties in ways that make sense in twenty-first century Canada. Such implementation should extend to agreements for the sharing of jurisdiction over a range of fields, for the sharing of access to natural resources, and for the sharing of royalties derived from the exploitation of natural resources.

The Assembly of First Nations, The Indian Act, and the Constitutional Legacy of the Royal Proclamation of 1763

The conflict between the Indian Act system and the repressed system of Crown-Aboriginal treaties in Canada is well expressed in the crisis that has engulfed the Assembly of First Nations (AFN), Canada’s most high-profile Aboriginal organizations. That crisis emanates from disagreements about a new Indian Act, Bill C-33, dealing with on-reserve schooling for registered Indian youths. Bill C-33 deals with the very topic that was central to the negotiation of most Crown-Aboriginal treaties. Virtually all of these agreements highlighted Crown promises to provide the educational help that Indian youths would need to meet the coming changes in Canada’s political economy.

In treaties 1-7, for instance, the Crown promised Cree, Blackfoot, Assiniboine, and Saulteaux peoples the help they would need to adapt to the end of the buffalo hunt and the coming of non-Aboriginal farmers along with the building of the CPR. The James Bay and Northern Quebec Treaty of 1975 was to prepare the way for Hydro-Quebec’s flooding of much of the traditional hunting territory of the Indigenous peoples. This emphasis on education in Crown-Aboriginal treaties raises the question of why Indian education is not being addressed through some explicit reckoning with the constitutional heritage of the Royal Proclamation and section 35 of the Constitution Act, 1982.

The leadership of the AFN is naturally inclined to emphasize the nation-to-nation attributes of Canada’s constitutional heritage in Crown-Aboriginal alliances. This propensity, however, runs against the structural reality that the AFN is an organization composed of 633 Indian chiefs elected according to the procedures of the Parliament of Canada’s Indian Act system. With some few exceptions, only those chiefs elected according to the Indian Act have a direct vote in choosing the National Chief of the Assembly of First Nations.

If the AFN is to put itself in a stronger position in Canada those who care about its future, including those that identify with the Idle No More movement, must meet the present crisis through a process of reorganization that better incorporates a more inclusive and broadly-based constituency not limited by federal definitions of Indian status. Moreover, if the AFN could render itself stronger and more internally consistent if it could better reflect in its internal organization the existence of Crown-Aboriginal treaty areas as well as areas that remain outside the frontier of Crown-Aboriginal treaties. Such a reorganization of the AFN would help Canada and all Canadians to embrace more vigorously the deepest and best part our country’s constitutional heritage.

In spite of all the lapses of amnesia and the shortfalls in implementing Crown-Aboriginal treaties, the constitutional heritage of the Royal Proclamation makes Canada a much-more-well-adapted-and-indigenized North American polity than the ailing superpower to the south. This overextended and debt-plagued superpower is foundering under the weight of the most massive military apparatus ever assembled in human history.

The huge compounding problems the USA is encountering globally and at home are not aberrations leading away from the wisdom of its founders. Rather they are realization of the problems inherent in a a polity created in a primal criminalization of Indigenous peoples as “merciless Indian savages.” This feature embedded in the founding manifesto of the United States is not some mere footnote to history but rather the basis of the US republic’s inevitable downfall if its people and government do not reckon with this fundamental flaw now on full public display in the serial speciousness of the absurdity known as the Global War on Terror.

The best we can do as the northern neighbors of the ailing superpower is not to rush to join its military incursions, adventures, and sabre rattling threats whether in Ukraine, Iraq or the next flavor-of-the-week site for invasion. It is not for Canada to continue as a obedient member of NATO, an organization that has strayed very far from its initial mission to defend the North Atlantic region from Soviet invasion.

Canada and Canadians would be much better served by cultivating peace, order and good government, the key phrase in the British North American Act whose deeper origins lie in the Royal Proclamation of 1763. Canada and Canadians would be well served by metaphorically polishing the silver links in an extended Covenant Chain reaching out to all the Aboriginal peoples of Canada.

The successful return of Canada to its own constitutional heritage of Crown-Aboriginal alliances might well establish a beacon of sanity to provide hope for so many menaced Indigenous peoples worldwide, including, for instance, Kurds, Palestinians, and Aboriginal Tibetans. In a world of 6,000 distinct languages, most of them endangered Aboriginal languages, the list is long of those distinct peoples awaiting some form of emancipation from the continuing oppressiveness of colonialism and neo-colonialism.

Anthony Hall is a Professor of Globalization Studies at the University of Lethbridge in Alberta Canada where he has taught for 25 years. Along with Kevin Barrett, Tony is co-host of False Flag Weekly News at No Lies Radio Network. Prof. Hall is also Editor In Chief of the American Herald Tribune. His recent books include The American Empire and the Fourth World as well as Earth into Property: Colonization, Decolonization and Capitalism. Both are peered reviewed academic texts published by McGill-Queen’s University Press. Prof. Hall is a contributor to both books edited by Dr. Barrett on the two false flag shootings in Paris in 2015.

Part II was selected by The Independent in the UK as one of the best books of 2010. The journal of the American Library Association called Earth into Property “a scholarly tour de force.”

One of the book’s features is to set 9/11 and the 9/11 Wars in the context of global history since 1492.

ATTENTION READERS

We See The World From All Sides and Want YOU To Be Fully InformedIn fact, intentional disinformation is a disgraceful scourge in media today. So to assuage any possible errant incorrect information posted herein, we strongly encourage you to seek corroboration from other non-VT sources before forming an educated opinion.

About VT - Policies & Disclosures - Comment Policy