“For the scientist who has lived by his faith in the power of reason, the story ends like a bad dream. He has scaled the mountains of ignorance; he is about to conquer the highest peak; as he pull himself over the final rock, he is greeted by a band of theologians who have been sitting there for centuries.”—Agnostic Astronomer Robert Jastrow[1]

…by Jonas E. Alexis

During the early part of the twentieth century, one popular movement among philosophers was logical positivism, which limited truth to what could be empirically verified by the five senses or experience.

During the early part of the twentieth century, one popular movement among philosophers was logical positivism, which limited truth to what could be empirically verified by the five senses or experience.

At its core, the movement sought to deconstruct revelation—chiefly theological assertions—or anything else that appeared to be beyond the five senses.[2] If something cannot be verified by the five senses, logical positivists dismissed them as meaningless.

Over the course of more than a decade, logical positivists launched their ideas with great energy and passion, willing to crush anyone who stood in their way.

Yet the movement could not gain much intellectual ground because its founding principle was self-defeating.

After all, can the proposition “any statement that cannot be empirically verified is meaningless” itself be empirically verified? No. It is an axiomatic proposition—nothing less, nothing more. In the end, logical positivism ceased to carry any intellectual weight and quietly slipped out of academia, although it continued to impact many people.

Of course, the verification principle was later modified by people like Sir A. J. Ayer in Language, Truth, and Logic, but that modification itself was fraught with logical inconsistency.

Ayer, who was largely responsible for spreading the gospel of logical positivism in England,[3] asserted in 1936 that “a proposition is said to be verifiable, in the strong sense of the term, if, and only if, its truth could be conclusively established by experience.”[4]

Yet this bold proposition fails to pass its own test. Ayer seems to have foreseen the implication of the statement, and moves on to declare that “if we adopt conclusive verifiability as our criterion of significance, as some positivists have proposed, our argument will prove too much.”[5]

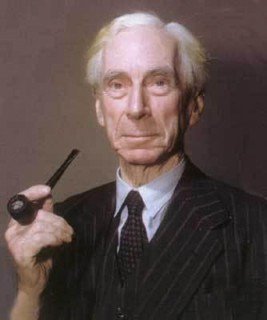

Ayer was, in the words of Paul Johnson, a “passionate disciple” of Bertrand Russell,[6] who was also a logical positivist.

Johnson was a close friend of both Russell and Ayer and discussed deep issues with them frequently.

By the 1970s, logical positivism was almost universally derided for its lack of intellectual rigor and obvious inability to cope with the experiential and scientific world.[7] Even Karl Popper, a noted Jewish philosopher of science, argued that at its eventual root, logical positivism would undermine the nature of the scientific enquiry.[8]

Popper was right, for the scientific enterprise is based on assumptions and presuppositions, and many conclusions are drawn using inference to the best explanations.[9]

The fact is that science itself is based on fundamental assumptions that cannot be proven by the scientific method—assumptions like the universe is rational, that it obeys mathematical and scientific laws, and that the rationality of the universe can be understood and can correspond to the rational human mind.

These assumptions are essential to science and yet they have not been proven by the scientific method. Moreover, these assumptions are perfectly congruent with the Christian and Muslim understanding.[10]

It was not just the sciences that are at stake, however, but ethical values and inferences, as well as history, because it by nature includes so many assumptions, many of which will be examined in the next two articles. For this reason, logical positivism was largely abandoned.

Even Ayer—the man who brought the movement to England—suddenly abandoned his atheist/agnostic stance after a near-death experience. He privately told his physician, Jeremy George, “I saw a Divine Being. I’m afraid I’m going to have to revise all my various books and opinions.”[11]

Yet in order to maintain his prestige as a philosopher, Ayer never mentioned this to anyone—not even his wife or son. George later wrote,

“He was confiding in me, and I think he was slightly embarrassed because it was unsettling for him as an atheist. He spoke in a very confidential manner. I think he felt he had come face to face with God, or his maker, or what one might say was God. Later, when I read his article, I was surprised to see he had left out all mention of it. I was simply amused. I wasn’t very familiar with his philosophy at the time of the incident, so the significance wasn’t immediately obvious.”[12]

Clearly Ayer was more interested in promoting his intellectual image than coming to grips with the afterlife. As he said in the essay written after his experience, “I trust that my remaining an atheist will allay the anxieties of my fellow supporters of the Humanist Association, the Rationalist Press, and the South Place Ethical Society.”[13]

As philosopher of science James Ladyman shows, logical positivism, though it appears to be quite young, actually had its inception in the eighteenth century in David Hume’s empiricism.[14]

Hume set a principle in his Inquiry Concerning Human Understanding that later proved self-destructive to his critique of theology (mainly Christian theology). He wrote,

“If we take in our hand any volume; of divinity or school metaphysics, for instance; let us ask, Does it contain any abstract reasoning concerning quantity or number? No. Does it contain any experimental reasoning concerning matter of fact and existence? No. Commit it then to the flames: for it can contain nothing but sophistry and illusion.”[15]

As some writers later proved, Hume’s bold declaration should have been dismissed with little thought or mental exercise, for it is neither mathematical nor scientific.[16] Moreover, Hume’s famous claims against miracles have also been proved completely erroneous.[17] He knew virtually nothing about the probability calculus that was later developed by mathematicians which seems to suggest that there is more to theological assertions than meets the eye and ear.

But—illogic notwithstanding—Hume’s dictum got refined and sharpened in the early 1920s among a group of mathematicians, scientists and philosophers called the Vienna Circle. Ladyman declares,

“Many of the Vienna Circle were Jewish and/or socialists. The rise of fascism in Nazi Germany led to their dispersal to America and elsewhere, where the ideas and personalities of logical positivism had a great influence on the development of both science and philosophy.”[18]

“Many of the Vienna Circle were Jewish and/or socialists. The rise of fascism in Nazi Germany led to their dispersal to America and elsewhere, where the ideas and personalities of logical positivism had a great influence on the development of both science and philosophy.”[18]

The philosophical idea of logical positivism was closely linked to naturalism, which simply says that nature is all that exists. Both ideas discount the existence of anything outside of what can be verified by our senses.

However, as attractive as this result was (and is) to many, logical positivism proved to be less than logical and had to be discarded.

The modern incarnation of logical positivism is relativism. Relativism in its metaphysical and categorical forms is neither logical nor coherent, and therefore cannot possibly be true.

Consider for example the person who utters the phrase, “There is no such thing as absolute truth.” This statement is either absolutely true or absolutely false. If it is true, then the statement logically self destructs, for it is nonsensical to assert absolutely that absolute truth doesn’t exist. On the other hand, if it is false, then we have no reason to believe anything the person says.

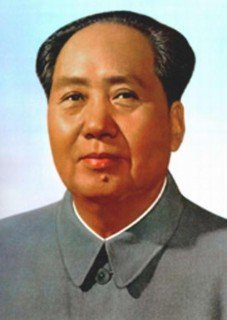

Let’s move this argument into a moral arena so that we get an accurate description of what is at stake here. If truth is simply based on cultural bias, individual preference, majority vote, or any other subjective criteria, we cannot say that the actions of Joseph Stalin or Mao Zedong were morally wrong.

Making any kind of moral statement proves that, at some level, human beings all act as though truth is absolute, no matter what we say we believe.

In the real world, moral truth must exist. If it does not, then we have no foundation from which to judge the numerous crimes against humanity that have been committed in the last century alone and prevent future human rights violations.

Moral truth must also be objective—bigger than humanity itself. It cannot be based on mere social contract, as Jean-Jacques Rousseau would argue,[19] or on “the community of individuals,” as Bertrand Russell[20] would say, or even on what you and I agree is right. Otherwise moral truth will constantly be redefined to fit the inclinations and ambitions of selfish men and women.

This was illustrated by Mao Zedong. Mao did not consult the laws of major nations to define basic human rights. Instead, he defined morality in terms of what he liked and disliked.

“Morality does not have to be defined in relation to others,” he said unapologetically. “Some say one has a responsibility for history. I don’t believe it. I am only concerned about developing myself…I have my desire and act on it. I am responsible to no one.”[21]

Mao’s subjective morality was eventually responsible for taking the lives of more than forty million people, according to historian Frank Dikotter of the University of Hong Kong, who has written a book about Mao based on documents from the Chinese archives.[22]

The fact is that history has proven time and again that mere agreement between those in power is not enough to safeguard against atrocity. Even if we grant relativists the premise that objective morality is based on the “pressure of the community on the individual,”[23] they still must face the ultimate question of why they are accepting the moral values of the community, since they believe that in the end everything will collapse.

Russell, after pondering the ultimate end of human existence, declared that humanity’s achievements will “inevitably be buried beneath the debris of a universe in ruins—all these things, if not quite beyond dispute, are yet so nearly certain, that no philosophy which rejects them can hope to stand.”[24]

Russell follows this with a conclusion based solely on his atheistic worldview: “Only within the scaffolding of these truths, only on the firm foundation of unyielding despair, can the soul’s habitation henceforth be safely built.”[25]

With such a cheerful outlook, it is no wonder why a reputable mathematician and philosopher like Bertrand Russell lived a life of despair, while his daughter, Katherine Tait, was able to make peace with the Christianity that Russell had attacked so vigorously.[26] And don’t forget that Russell was a logical positivist.

If communal agreement is proven not to be a valid foundation for morality, many turn to a biological explanation. Philosopher of science and atheist Michael Ruse of Florida State University (who has become progressively more honest in recent years[27]) wrote back in 1989 that the best that can be said about morality is that it is a biological adaptation.

“I appreciate when somebody says ‘Love thy neighbor as thyself,’ they think they are referring above and beyond themselves…Nevertheless, to a Darwinian evolutionist it can be seen that such reference is truly without foundation. Morality is just an aid to survival and reproduction…an ephemeral product of the evolutionary process, just as are other adaptations. It has no existence or being beyond this, and any deeper meaning is illusory.”[28]

Bertrand Russell likewise noted in Why I Am Not a Christian that “outside human desire there is no moral standard.”[29] (By the way, after I became a Christian, I was hoping that Russell’s Why I Am Not a Christian would disprove the tenets of Christianity. I was very disappointed after I’ve read it. The book is fraught with circular arguments, illogical leaps, and indefensible conclusions. More on that on a specific article.)

Although this view of morality is extremely prevalent (to the point of becoming axiomatic), it categorically fails to correspond to the real world as we know it, for we constantly refer to universal moral laws either directly or indirectly.

To return to real-world illustrations, objective moral truth simply states that Stalin was wrong irrespective of what he and the Bolsheviks believed, and Mao was wrong despite his evolutionary belief that those who could not adapt to his ethical codes had to vanish.

Michael Ruse’s definition certainly suffers badly here. Who are we to say that these leaders were wrong if in fact they were simply following relativistic principles to their logical conclusions?

Yet everyone feels in his or her soul that the atrocities against humanity these leaders carried out are in fact wrong.

Yet although many lack a firm foundation for their denial of absolute truth, they remain adamantly opposed to it.

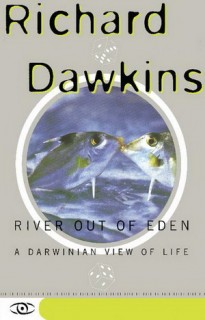

Richard Dawkins demonstrated some years ago where his atheistic worldview is taking him in his widely read book River Out of Eden: A Darwinian View of Life.

Richard Dawkins demonstrated some years ago where his atheistic worldview is taking him in his widely read book River Out of Eden: A Darwinian View of Life.

“In a universe of blind physical forces and genetic replication, some people are going to get hurt, other people are going to get lucky, and you won’t find any rhyme or reason in it, nor any justice. The universe we observe has precisely the properties we should expect if there is, at bottom, no design, no purpose, no evil, and no good, nothing but blind pitiless indifference… DNA neither knows nor cares. DNA just is. And we just dance to its music.”[30]

On a philosophical level, Dawkins is quick to assert that there is no good or evil. However, on a practical level, he lives by the principle that good and evil do exist. Otherwise, how can he logically write The God Delusion?

If Dawkins truly believes that there is no rhyme or reason to the universe, then why is he so angry at both the Old and the New Testament? On what grounds can he rationally condemn Stalin? Wasn’t he just dancing to the music of his DNA?

On the eve of his intellectual fame, Dawkins was asked the following question:

“Suppose some lads break into an old man’s house and kill him. Suppose they say: ‘Well, we accept the evolutionist worldview. He was old and sick, and he didn’t contribute anything to society.’ How would you show them that what they had done was wrong?”

Listen to Dawkins’ response very carefully:

“If somebody used my views to justify a completely self-centered lifestyle, which involved trampling all over other people in any way they chose, roughly what, I suppose, at a sociological level Darwinists did, I think I would be fairly hard put to it to argue on purely intellectual grounds. I think it would be more: ‘This is not a society in which I wish to live. Without having a rational reason for it, necessarily, I’m going to do whatever I can to stop you doing this.’”

The brilliant interviewer then pressed the question forward. “They’ll say, ‘This is the society we want to live in.’”

Dawkins replied,

“I couldn’t, ultimately, argue intellectually against somebody who did something I found obnoxious. I think I could finally only say, ‘Well, in this society you can’t get away with it’ and call the police. I realize this is very weak, and I’ve said I don’t feel equipped to produce moral arguments in the way I feel equipped to produce arguments of a cosmological and biological kind.”[31]

Morality, as defined from within a purely atheistic worldview, is merely a social construct. In a widely viewed debate between philosopher William Lane Craig and Massimo Pigliucci (evolutionary biologist and Chair of the Department of Philosophy at the University of New York), Pigliucci unambiguously stated,

“There is no such thing as objective morality. We got that straightened out. Morality in human cultures has evolved and is still evolving, and what is moral for you might not be moral for the guy next door and certainly is not moral for the guy across the ocean.”[32]

There is certainly an obvious contradiction among atheists in this area. G. K. Chesterton points out the futility of their thinking this way:

“The new rebel is a Skeptic, and will not entirely trust anything. He has no loyalty…and the fact that he doubts everything really gets in his way when he wants to denounce anything. For all denunciation implies a moral doctrine of some kind; and the modern revolutionist doubts not only the institution he denounces, but the doctrine by which he denounces it…

“As a politician, he will cry out that war is a waste of life, and then, as a philosopher, that all life is a waste of time. A Russian pessimist will denounce a policeman for killing a peasant, and then prove by the highest philosophical principles that the peasant ought to have killed himself. A man denounces marriage as a lie, and then denounces aristocratic profligates for treating it as a lie.

“He calls a flag a bauble, and then blames the oppressors of Poland or Ireland because they take away that bauble. The man of this school goes first to a political meeting, where he complains that savages are treated as if they were beasts; then he takes his hat and umbrella and goes to a scientific meeting, where he proves that they practically are beasts.

“In short, the modern revolutionist, being an infinite skeptic, is always engaged in undermining his own mines. In his book on politics he attacks men for trampling on morality; in his book on ethics he attacks morality for trampling on men. Therefore the modern man in revolt has become practically useless for all purposes of revolt. By rebelling against everything, he has lost his right to rebel against anything.”[33]

Chesterton certainly nails it. If there is no such thing as good and evil, it would be a perfectly legitimate parallel argument to say that there are no real differences between a Richard Dawkins or a psychopath, a Sam Harris or a serial killer, a Daniel Dennett or a suicide bomber.

Without an objective moral reference, the world becomes neutral grey, with no idea or action ranked better or worse than anything else. No one can ever claim they have been wronged, no one can rely on unalienable human rights, and no one can expect justice or fairness.

Dawkins and others simply cannot have it both ways, and their contradictory beliefs and behaviors prove just why relativism does not work in the real world.

Let me make it clear here that I am not arguing for an epistemological foundation of objective moral values, but rather for an ontological foundation of objective moral values.

In other words, I am not saying that an atheist does not or cannot make reference to an objective moral value, or that moral values are the sole province of religious people. Neither the atheist nor the theist needs God to recognize morality. It is ingrained in human nature.

For example, if a sexual predator rapes a twelve-year-old child, both the theist and the atheist would say that this act is morally wrong.

Some have called this the law of human nature.[34] Even Emmanuel Kant, one of the toughest philosophers during the end of the eighteenth century, made this stunning statement in his Critique of Practical Reason:

“Two things fill the mind with ever new and increasing admiration and awe, the more oftener and the more steadily we reflect upon them: the starry heavens above me and the moral law within me.”[35]

Kant made it clear that ethical values are completely independent of our happiness.[36] If they are independent of our happiness, then ethical values lie somewhere else. Therefore, Kant, whether he liked it or not, was arguing from an implicitly Christian viewpoint. Pure reason, ultimately, leads to the Logos.

Pure reason, like mathematics or physics, is non-negotiable and is completely compatible with the Christian worldview.

So let’s break it down into simple terms. All people can agree that it is wrong to steal, covet another man’s wife, or torture and rape little children. The question is where did that objective moral judgment come from? We know that it is not from Darwinism (a topic I will go into in more details in future articles).

Let me be crystal clear before we move on—I am not claiming that atheists cannot live moral lives or appeal to moral objectivity. To a large degree, both theists and atheists appeal to objective moral values and truths.

Sam Harris agrees with the premise that objective moral values do exist.[37] What he disagrees with, however, is that such values cannot exist without God; for him, objective moral values can be explained through the emergence of the scientific enterprise.

Yet not one Darwinian principle suggests that objective moral values are independent of what you and I think. Therefore, the core issue is not whether objective moral values exist, but whether objective (ontological) moral values can exist without God. One well-known philosopher who clearly understood that there were no morals without God is Friedrich Nietzsche.

Nietzsche took that principle to its logical, bitter end,[38] something that Sam Harris, Richard Dawkins and others have not been willing to do.

Not only does Harris fail to give us a rigorous scientific rubric by which to examine the thesis that “science can determine human values,” but he moves on to tell us that moral responsibility “is a social construct that can make more or less sense given certain facts about a person’s brain.”[39]

With nowhere else to turn, Harris jumps to determinism. Citing neuroscientist Michael Gazzaniga, he agrees that “in neuroscientific terms, no person is more or less responsible than any other for actions.”[40]

We will return to this premise in a future article. For now, though, let’s continue our discussion of objective values in the cultural realm of relativism.

Relativism also does not work within the world’s major religions, for all religions make exclusive claims that simply cannot be reconciled. Islam teaches that Christ did not die on the cross, Rabbinic Judaism is still looking for its Messiah, and Christianity declares that Christ has already appeared, died, and rose again.

Buddha, the figurehead for Hindu beliefs, rejected both the Vedas and the caste system, which are fundamentally essential to Hinduism.[41] He even rejected the existence of the supernatural altogether,[42] while other religions affirm it.[43]

Given this widespread dichotomy, it is nonsensical to say that all these religions teach the same things or that they lead to the same conclusions. While they may share many themes in common here and there, ultimately they make exclusive claims that are vital to their continued existence.

Moreover, it is completely irrational to say that all these religions lead to the same God. Oprah Winfrey, one of the most influential women in America, says,

“I’m a Christian who believes that there are certainly many more paths to God other than Christianity.”[44]

Although many paths claim to lead to what one might call god, it contradicts logic to say that all those religions lead to the same God or gods. As Ravi Zacharias, an expert on world religions, points out,

“All religions are not the same. All religions do not point to God. All religions do not say that all religions are the same. At the heart of every religion is an uncompromising commitment to a particular way of defining who God is or is not and, accordingly, of defining life’s purpose.”[45]

Jesus declares, “I am the way, the truth, and the life: no man cometh unto the Father, but by me” (John 14:6). Can we honestly say that Jesus and other religions are equally right—when they clearly contradict each other—and still remain reasonable?

More importantly, what are the features that enable an individual to be “inclusive” or “exclusive” and still remain rational?

It is not illogical to be exclusive, since rationality demands it.[46] It is much more rational to be exclusive when all the religions are contradictory.

The fact is that Jesus is not being irrational when He proclaims that there is only one way to get to God. His claim is perfectly within the realm of the reasonable. In that context, the rational human response is to discover where the rational and irrational exist in the major religions and to discern whether exclusivity is based on truth or not.

It is not narrow-minded to reject contradictions, nor is it irrational to argue that one religion might be telling the truth, wherever that religion may lead. According to the basic principles of logical consistency, contradictory religious claims cannot all be right at the same time and in the same respect.

It is not narrow-minded to reject contradictions, nor is it irrational to argue that one religion might be telling the truth, wherever that religion may lead. According to the basic principles of logical consistency, contradictory religious claims cannot all be right at the same time and in the same respect.

As a corollary, there is an often ignored but vital principle that must be clearly emphasized here:

Philosophically, the denial of the only way is another only way. Rejecting any religion on the grounds of exclusivity means setting up an opposing but equally exclusive belief system.

Once a person states that “Christ is not the only way—there are more ways to God,” he has made an implicit “only-way” claim. If the person protests that he is not making an “only-way” claim, but merely accepting other views into his equation, then logically he has to accept the possibility that Christ could be right, which would negate his stated claim.

Either his process of logical reasoning is flawed or he is grasping at straws in order to justify his claim.

Finally, it is irrational for anyone to claim that because all religions, at bottom, contradict each other, therefore none of them is telling the truth. If I cannot find an answer to a math problem, or happen to arrive at an answer that contradicts what my friends come up with, it does not necessarily follow that the answer cannot be found or that there simply is no answer at all.

It must be said that truth sometimes does not bring good news. For example, if a doctor finds out that one of his patients has terminal cancer, he is obligated to tell the man the truth about his condition. It would be morally irresponsible for the doctor to say, “Don’t worry, my friend. Everything is all right. Just take this pill or that medicine and your pain will be gone forever.”

Although it would be much easier to lie and spare the patient worry—and although it would be compatible with the relativistic premises we have just discussed—the doctor would put his credibility at stake for lying to the patient. He would not be a doctor for long, once the truth came out.

More importantly, the patient would not want his doctor to behave as a relativist, since going to the doctor implies that he believes truth about his condition exists and that he wants to be told that truth.

However idealistic someone’s opinions may be concerning relativistic ideology, he or she will live as if truth matters when it comes to going to the doctor, buying a car, or paying taxes and bills—the simple truth is that you won’t have running water or electricity if you don’t pay your bills. Although it may be painful to accept the truth, in the end it will be worth it, for only truth has the ability to liberate us from falsehood and intellectual bondage.

[9]For a technical study, see Peter Lipton, Inference to the Best Explanation (New York: Routledge, 1991).

[10]For further study, see John D. Barrow, Impossibility: The Limits of Science and the Science of Limits (New York: Oxford University Press, 1998); Muzaffar Iqbal, Science & Islam (Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 2007); Ahmad Y Hassan and Donald Routledge Hill, Islamic Technology: An Illustrated History (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1986); George Saliba, A History of Arabic Astronomy: Planetary Theories During the Golden Age of Islam (New York: New York University Press, 1994).

[11] Peter Foges, “An Atheist Meets the Masters of the Universe,” Lapham’s Quarterly, March 8, 2010.

[13] A. J. Ayer, “What I Saw When I Was Dead” (available at http://commonsenseatheism.com/wp-content/uploads/2009/11/Ayer-What-I-Saw-When-I-Was-Dead.pdf.

[15]David Hume, An Inquiry Concerning Human Understanding and Other Essays (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2007), 144.

[17] For a technical study, see John Earman, Hume’s Abject Failure: The Argument Against Miracle (New York: Oxford University Press); Francis Beckwith, David Hume’s Argument Against Miracles (Lanham: University Press, of America, 1989).

[24]Bertrand Russell, Mysticism and Logic & Other Essays (New York: Cornell University Press, 1918), 48.

[27] See Michael Ruse, “Accomodationism in the Religion-Science Debate: Why It’s Incomplete,” Huffington Post, November 6, 2010; Michael Ruse, Science and Spirituality: Making Room for Faith in the Age of Science (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2010).

[28]Michael Ruse, The Darwinian Paradigm: Essays on its History, Philosophy, and Religious Implications (New York: Routledge, 1989), 268-269.

[29]Bertrand Russell, Why I Am Not a Christian and Other Essays (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1957), 62.

[30]Richard Dawkins, River Out of Eden: A Darwinian View of Life (New York: Basic Books, 1995), 133.

[31] Nick Pollard, “The Simple Answer,” Third Way, April 1995, 16-19 (archived at www.ThirdWayMagazine.co.uk).

[37]Sam Harris, The Moral Landscape: How Science Can Determine Human Values (New York: Free Press, 2010), 46.

[42]Rodney Stark, One True God: Historical Consequences of Monotheism (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2001), 11-12.

[43] This is why atheists like Sam Harris prefer Buddhism as a replacement for other religions. “The Buddhist tradition…represents the richest source of contemplative wisdom that any civilization has produced. In a world that has long been terrorized by fratricidal Sky-God religions, the ascendance of Buddhism would surely be a welcome development.” (Sam Harris, “Killing the Buddha,” Shambhala Sun, July 2009.)

[46]For a sociological perspective, see Rodney Stark, One True God: Historical Consequences of Monotheism (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2001) and Discovering God: The Origins of the Great Religions and the Evolution of Belief (New York: HarperOne, 2007).

Jonas E. Alexis has degrees in mathematics and philosophy. He studied education at the graduate level. His main interests include U.S. foreign policy, the history of the Israel/Palestine conflict, and the history of ideas. He is the author of the new book Zionism vs. the West: How Talmudic Ideology is Undermining Western Culture. He teaches mathematics in South Korea.

ATTENTION READERS

We See The World From All Sides and Want YOU To Be Fully InformedIn fact, intentional disinformation is a disgraceful scourge in media today. So to assuage any possible errant incorrect information posted herein, we strongly encourage you to seek corroboration from other non-VT sources before forming an educated opinion.

About VT - Policies & Disclosures - Comment Policy