The item below helps to illuminate the next round in the Canadian government’s political prosecution and persecution of Kwitsel Tatel. Readers are invited to join with Kwitsel Tatel to expose Canada in international arenas for its grotesque human rights violations at home in order to push Aboriginal peoples off their remaining lands, waters and resources to facilitate the agenda of, for instance, Big Oil, Dirty Oil, pipeline companies, disease-generating fish farms, biodiversity-destroying clear cutting, the nuclear weapons/energy industry, and Canada’s internationally-reviled mining industry. Expose the lies and crimes of the Harper government and its deployment of the likes of Prof. Tom Flanagan, Finn Jensen QC, Dr. Alexander von Gernet plus many more patronage cronies. They are paid handsomely from public funds to assist with the litigious denial and negation of existing Aboriginal and treaty rights, which are to be “recognized and affirmed” according to section 35 of Canada’s Constitution Act, 1982. Help Kwitsel Tatel stand up to the crime spree of the election-fraud government of Stephen Harper. The government of Canada must face some accountability for its violations of its own constitutional law. These violations are directed at all Canadian citizens except a small minority of the very wealthy, many of them outside Canada. The Harper government’s crime spree is directed with particular intensity at the Aboriginal peoples of Canada who must lead the freedom movement against the tyranny of the Canadian police state as presently being engineered by the Harper cabal.

Please be Idle No More. Stand up to the malevolent forces of corporatist globalization that are impoverishing the life chances of most people and peoples on the planet as well as our plant and animal relatives that face serial rounds of extinction at an accelerating pace. Enough is enough! The global community needs a new political economy. The logical groups to lead the way the way are those Indigenous peoples who have opposed imperial, national and corporate globalization since 1492. Students of the world, veterans of the world, workers of the world, parents of the world, decent men and women of the world, UNITE. We have nothing to lose but the tyranny of a global police state where most people and peoples are enchained by the growing bondage of debt slavery!

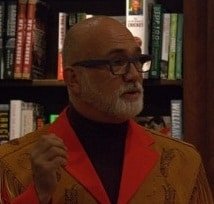

The trial proceedings in the case of the Queen and Kwitsel Tatel versus the Government of Canada resume in the Chilliwack Law Courts of BC on May 9,10, 13, and 14, when Prof. Hall will take the stand for his expert testimony on the conflict-of-interest issues permeating this matter.

Chief Judge of the Provincial Court of British Columbia,

Presiding judge in the Case of The Queen and Kwitsel Tatel versus the Government of Canada, Trial 47476

23 April, 2013

Dear Judge Crabtree;

[1] This communication is in response to the tele-court proceedings involving you and I and Mr. Finn Jensen QC on Monday April 15 and Friday April 19. The first conversation lasted about 15 minutes whereas the second session of the telephone proceedings went on for about an hour.

[2] The more substantive proceedings of April 19 started with a reference to my prior written request stated, forwarded in an E-Mail to Chilliwack Court registry Manager, Ms. Lunde, for a document camera to facilitate the forthcoming proceedings of the expert witness planned for May 9, 10, 13, and 14. Much to my surprise, Your Honour, you opted to transform this request into a lever of negotiation to make new demands of Prof. Anthony Hall. You conveyed, seemingly on Mr. Jensen’s behalf, the demand that Prof. Hall must produce a list of documents on which you both surmise he intends to rely on in his forthcoming testimony. Mr. Jensen indicated his desire to vet the proposed documents for “relevance” and what the two of you described as “permissibility.”

[3] I indicated in the tele-court proceedings of April 19 that I was in no position to respond one way or another to the new demands you are now making of Professor Hall. Professor Hall is a busy senior academic engaged at the moment in completing his teaching term involving evaluations of essays, presentations, and final exams of students together with the calculation of their final grades. Prof. Hall tells me that he hopes to be able to wrap up the final term by April 26. As I conveyed in tele-court, Prof. Hall is a tenured scholar at a Canadian university who is assisting the court with his expertise in the history of constitutional relations between Aboriginal peoples and the Crown without any compensation whatsoever.

[4] Prof. Hall has already fulfilled the pre-trial part of the instructions you gave him on September 25 by submitting a report on March 26 to meet the 45-day requirement you put on him. As you will recall, you wanted Prof. Hall to come up with his report 45 days before the May 9-13 proceedings begin. He has done as you requested.

[5] As I recall your instructions of Sept. 25, which you have not to this day forwarded in writing to either Prof. Hall or I, make no reference to a requirement for a list of documents. Nevertheless the report Prof. Hall has already submitted does refer to documents and a number of specific rulings that address the issue of the honouring and dishonouring of the Crown in the treatment of the Aboriginal peoples of Canada. Could we please have copies of your ruling of September 25. Surely I should not have had to ask. Surely this ruling should have been forwarded to both Pr. Hall and I without our having to make this specific request. Please consider this statement as a formal request for your ruling of Sept. 25. The Court Registry has my address. Prof. Hall can be reached at Globalization Studies, University of Lethbridge, A-812 University Hall, 4401 Columbia Blvd, Lethbridge Alberta, T1K 3M4.

[6] As I indicated I would, I arranged a meeting with Prof. Hall where I conveyed to him your new requests or demands and where I related to him some of the ideas, views, and interpretations that came up in the course of the proceedings among the three of us on April 15 and 19. I conveyed to Prof. Hall, for instance, that you, Judge Crabtree, had not yet seen, let alone read, the Hall report almost a month after he sent it to your attention through the Chilliwack court registry. I told Prof. Hall that, on the other hand, Mr. Jensen had read the Hall report. I indicated further that you requested Mr. Jensen to describe the Hall report for you. Mr. Jensen then characterized the Hall report for you in a decidedly self-serving and biased manner completely consistent with the federal Crown prosecutor’s consistent adversarial denial and negation of Aboriginal rights.

[7] Prof. Hall tells me he did not send the Hall report directly to Mr. Jensen given that on March 26 the federal Crown prosecutor’s conflict-of-interest was still subject to your arbitration. Prof. Hall tells me he did send a copy to the Ministry of Justice in BC. Apparently while the Hall report was gathering dust in the Chilliwack court registry, the BC office of the federal Ministry of Justice’s copy found its way to the Attorney-General of Canada’s private contractor in the Hope/Chilliwack/ Fraser Canyon area.

[8] I must say, Your Honour, I found it woefully inappropriate when you called on Mr. Jensen to present his characterization of the Hall report in the absence of your own independent reading and evaluation of the document. Do you regularly rely on Crown prosecutors to help you out by explaining for you submissions from the other side when you have not been able to get around to doing your own homework? Your apparent taking of sides so obviously in the prelude to the May 9-13 proceedings is illustrative once again of the decided bias and inequity of your mismanaged provincial court. In my view you and Mr. Jensen once again ganged up on me on April 19 in a fashion that has become all-too-familiar. As I write this comment I have before me the transcripts of the June 4, 2010 proceedings when your examination of me from the Bench amounts to a proxy cross-examination for Mr. Jensen as if as if Section 35 did not apply to this case.

After the April 19 gang up I again I found myself traumatized by the abuse embedded in your unfair and unjust adversarial system devoted religiously to the denial and negation of the existing Aboriginal and treaty rights of the Aboriginal peoples of Canada. As proclaimed from the British imperial emblem appearing on the wall behind you in your predatory and ethnocentric court, “Dieu” is your “droit.” But my law is derived from Chi Chulh Si-yam.

[8] I ask myself why you cannot seem to keep up with the paper correspondence in the KT case, both in terms of your receiving material and in terms of your sending out material. In the same E-Mail to Ms. Lunde where I first noted my request for a document camera, I have raised the problem of the mysteries surrounding the conflicting evidence concerning the timing of the writing and sending of your ruling that defends Mr. Jensen’s obvious conflict-of-interest. Once again I am experiencing the same telling silence that generally prevails whenever I request some accountability from Crown officials, including you, involved in this maladministration of justice. How do you explain, Yout Honour, the evidence suggesting your ruling document of April 3 or April 5 or April 9 may included dates and related information that may have been forged, or deleted, or otherwise tampered with, or misrepresented?

[9] Are there no FAX links or E-Mail connections between your own office in Vancouver and the Chilliwack Court registry? Do you lack sufficient administrative assistance to keep you up to speed on the information flow in the case of Kwitsel Tatel? Why did you not come to the April 19 meeting properly prepared to discuss pre-trial procedures done and pre-trial procedures still left undone for the May 9-13 proceedings. Why were you, Judge Crabtree, by far the weakest link in our communications chain? Why didn’t you, with all the staff and resources available for your judicial work, come to the tele-court proceedings with some technological preparation instead of keeping us all waiting for ten minutes or so as you went for assistance in trying to figure out to make the microphone at your communication station work properly?

[10] What prevented you from being able to read the Hall report for yourself before the April 19 session? Why, Your Honour, did you come to the April 19 telephone session so completely unprepared on the matter of the Hall report and yet so certain about the importance of Mr. Jensen’s demand for a list of documents? Why did you invite Mr. Jensen in the April 19 session to characterize Professor Hall’s March 26 report prior to your evaluating independently the document for yourself? The prejudice you displayed against me and for Mr. Jensen on April 19 was made very clear. I request a transcript of those court proceedings for the written record of this unfair trial.

[11] In his adversarial zeal to win this case Mr. Jensen, I believe, has a decided interest in prejudicing your view against Prof. Hall’s scholarly advice to the court generally and against Prof. Hall’s report more specifically. Mr. Jensen is now obviously engaged in the effort to circumscribe and minimize and demean Prof. Hall’s expert opinion to the court in ways that match the federal Crown prosecutor’s own BC isolationist, anti-intellectual, anti-Aboriginal and anti-section 35 biases.

[12] Are the heavy biases displayed by Mr. Jensen typical of the necessary job qualifications to represent the Ministry of Justice, and, by implication, the people and government of Canada, in litigation involving Aboriginal matters? From what was said on April 19 it looks to me like Mr. Jensen has already succeeded in his goal of tarnishing your first impression of the Hall report before you even saw it for yourself even though it was sent to you three weeks prior our tele-court conference last Friday.

[13] As I see it, Your Honour, your dependence on Mr. Jensen for your initial understanding of the Hall report demonstrates yet another instance of bias in this unfair trial that is demonstrably in the wrong jurisdiction. Moreover, it shows Mr. Jensen has not been influenced by the cautions you put before us in your conflict-of-interest ruling emphasizing the high public trust he is carrying in this matter.

The Importance of Hearing Both Sides in the Process of Bringing New Documentary Evidence into the Trial of Kwitsel Tatel

[14] I shall now turn to Professor Hall’s response to my conveyance to your new request or demand that he produce a list of documents on which he intends to base his testimony of May 9 to 13. Professor Hall indicated that he has already produced a two-page report meeting your instructions of September 25 that he must produce such a document 45 days before the May 9 resumption of the trial. You indicated to Prof. Hall and I from the Bench near the end of the Sept. 25 proceedings that a one-page report would suffice.

[15] Prof. Hall’s response to your new layer of requests or demands needs to be understood in the context of the background of his experience as an expert witness before the Ontario Superior Court of Justice in the North Bay in the trial of Ronald Peter Joseph Pierre Fournier and Denise Beatrice Menard and Claude Bergeron. As you know, Your Honour, you imported from Ontario federal court into your own provincial court much of Judge J.S. O’Neill’s rulings on Prof. Hall’s expert qualifications. http://www.canlii.org/en/on/onsc/doc/2005/2005canlii24244/2005canlii24244.html

[16] With this background in mind let me turn again to Prof. Hall’s response to your new demands that he should adhere to the new round of instructions you sought to impose on him through me in the course of the tele-court proceedings of April 19. In our meeting after April 19 Prof. Hall indicated to me that there would be no sound basis for Mr. Jensen or you, Your Honour, to make a pre-trial assessment of the relevance of any particular document or list of documents absent some explanation from Prof. Hall himself on how he sees questions of relevance on a point by point, theme by theme, item by item basis. Recall, moreover, that your mismanaged court has not been able to get to Prof. Hall a copy of your Sept. 25 ruling that would help him in making his own determination of what is relevant or not.

[17] In the course of my discussion with Prof. Hall he indicated that each and every document might be used in one or more of any numbers of ways. A document, for instance, might be offered up in its totality as an authority for a particular argument. A document might be used to help set up a straw man argument, to provide evidence of the wrongness or absurdity of some point Prof. Hall may want to refute. A document might be used as a bridge to show connections between seemingly unconnected topics. A document might be used as a foil of some sort. A document might contain a single quote from a primary source that would help support an argument completely unrelated to the main subject matter of the text in question. In short, there would be no way for you or Mr. Jensen to know what Prof. Hall intends simply by simply looking at a document or at a list of document citations in isolation from Prof. Hall’s own statement of purpose about his own conception of relevance. Thus there are no easy short cuts to arguing through issues of evidentiary relevance in open court on case by case, theme by theme, item by item basis.

[18] How do you see the process, Your Honour, for me and for Mr. Jensen and for Prof. Hall to argue through questions of relevance and admissibility in your provincial court? Was the intent of your April 19 intervention to come up with some pre-trial procedure vesting you and Mr. Jensen with arbitrary powers to vet Prof. Hall’s documents without consulting either me as a self-representing defendant or Prof. Hall? If that was the intention of you and Mr. Jensen on April 19 I object. I object strongly. I do will not agree with or sanction this proposal or instruction or demand. As I see it a procedure to address the crucial issue of determining evidentiary relevance must take place in open court with sufficient time assigned to argue through matters of contention on a case by case, theme by theme, item by item basis. Moreover the format of this juridical process must be transferrable to meet my request outlined in more detail below that this litigation must be moved to a juridical venue equipped with the proper jurisdictions and capacities and personnel to provide genuine third-party adjudication?

[19] As I understand from Professor Hall, he sees himself to be at a stage in his career where he is in a position to give expert testimony that may have behind it dozens or even hundreds or even thousands of items he has read over the years. He is a full professor with major publications of his own. He is widely recognized for the originality of many of his interpretations that, as the extensive endnotes in the two peer-reviewed volumes of the Bowl With One Spoon attest, are supported by vast and elaborate documentation.

[20] Prof. Hall must be understood to be much more than a fact collector engaged in doing charitable work for the biased and inequitable BC provincial court that apparently has not heard of the fiduciary responsibilities to Aboriginal peoples it systemically denies and negates at every turn. What Prof. Hall brings to the Aboriginal rights question in BC, Canada and the world is fresh interpretation much needed especially in the stale atmosphere of the Chilliwack Law Courts where the oldest human rights issue in the province, country and hemisphere are regularly given short shrift. Rather than demean Prof. Hall as a collector of facts derived from others, both you and Mr. Jensen would be better advised to welcome and absorb what this accomplished scholar can bring to the study of Aboriginal and treaty rights. Can you and Mr. Jensen moderate your adversarial system and instincts to at least consider for a few hours of collaborative work what true Crown recognition and affirmation of Aboriginal and treaty rights might look like?

[21] As it now stands Mr. Jensen, who as far as I know is not known for his own academic scholarship, speaks of Prof. Hall as if he is some sort of graduate student whose assignment is to gather up documentary evidence and put it before the court as self-explanatory proofs of this point or that point. In our Meeting subsequent to April 19 Prof. Hall made himself very clear that a mere list of documents presented without discussion and without explanation of his own understandings of relevance would be insufficient for you or Mr. Jensen to make your own assessments of relevance. It can come as no secret that both Prof. Hall and I consider section 35 of the Constitution Act 1982 to be extremely relevant and necessary to the core facts of this Aboriginal rights case. What is equally clear is that both you and Mr. Jensen persist in resisting the implications of section 35 in the day-to-day conduct of your own juridical work.

[22] What would be the substance of the new overlay of April 19 rules, now given on top of the original Sept. 25 instructions leading to Prof. Hall’s March 26 report? Say Prof. Hall did come up with a list of 10 or 100 or 1000 documents? Would Prof. Hall then be limited to cite evidence only from those documents minus those Mr. Jensen will certainly want to vet in the name of his circumscribed and biased understanding of relevance; in his adversarial zeal to win rather than to see the full array of relevant facts come to light in the process of moving towards adherence to the rule of law, in the process of moving toward implementation and enforcement of section 35 of the Constitution Act 1982?

[23] Were you and Mr. Jensen seriously contemplating on April 19 going ahead with your own invented process without calling on Prof. Hall or without calling on me as a self-represented defendant to argue points of relevance on a case-by-case, theme-by-theme, item-by-item basis in open court? If you were contemplating the imposition of such an invented pre-trial procedure as you articulated on April 19, then you need to stop for some self-reflection on your own shared biases and lack of respect or understanding for the real meaning of due process. Such an invented process on the relevance of evidence is unacceptable to me in my four capacities in this matter.

[24] In the KT case I am the defendant as well as the legal representative of my own person. Because I have been criminalized for upholding the laws of my own Sto;lo people, it also falls on me to represent in court all the Aboriginal peoples of Canada. We, the Aboriginal peoples of Canada, all share a huge stake in how section 35 is being manipulated to our disadvantage by jurists like you and Mr. Jensen. Since your provincial criminal court, Your Honour, has also pre-empted the substance of the BC Crown-Aboriginal Treaty process, I am also carrying the responsibility of those negotiations.

Taking Stock of the Implications of the Crown’s Decision to Treat the Defence Side in the KT Case as a Public Charity

[25] I think it time for you to consider, Your Honour, what does and should flow from your importation of much of the ruling of the federally-appointed judge, the Hon. J.S. O’Neill, in coming to your own ruling on Prof. Hall’s expert qualifications. I think it time for you to consider the rules of evidence as applied in Prof. Hall’s expert testimony in 2005 in the Fournier case. Prof. Hall’s evidence turned out to be the lead-up to the provincial Crown’s staying of the criminal charges against the accused a week before the expert’s cross–examination was scheduled to begin. In an earlier stage of the Fournier Judge O’Neiil ordered in 2004 that $35,000 should be made available on order for Prof. Hall to prepare a pre-trial report to lay out the documentary evidence underlying a modified version of his constitutional questions brought forward by Fournier’s lawyer, Michael Swinwood.

[26] The provincial Crown refused to cooperate with the funding order. Demonstrating yet again the travesty of the adversarial system in maters pertaining to section 35, the provincial prosecutor appealed Judge O’Neill’s funding ruling to a higher court. Nevertheless Prof. Hall agreed to give evidence without compensation. Prof. Hall’s condition, however, was that he would not prepare a pre-trial report but would give the evidence behind the formulation of his constitutional questions directly from the stand. When he took the stand in 2005 Prof. Hall asked Judge O’Neill that the court provide him with the medium a document camera with a digital projector to help the judge, the prosecutor, other court staff and those in the galley to see the actual evidence displayed as it was put forward.

[27] Prof. Hall’s involvement in the KT trial is similar in that he has agreed to work for the court without compensation. His position is that the Crown’s denial of proper remuneration to him for his valuable professional services to address in court constitutional issues of national importance should come with some strings attached. As Prof. Hall sees it, Judge Crabtree, you have already well demonstrated your unwillingness to adhere to the rule of law as expressed in section 35 by not going to bat, as Judge O’Neill did in Ontario in 2004, by attempting with your jurisprudence to bring about even minimal equalization of the resourcing playing field so that fundamental constitutional issues of pressing national importance can be brought to light against the onslaught of the Hon. Rob Nicholson’s federal Crown prosecutor. Your Sept 25 requirement for a pre-trial report and now your April 19 demand, at Mr. Jensen’s behest, for lists of documents is not in conformity with Judge O’Neill’s adaptation to the resourcing inequity that arises because of the Crown’s consistent propensity to deny and negate existing Aboriginal and treaty rights in court.

[28] Let’s revisit how some of these matters began to first arise in the KT trial in the Chilliwack Law courts on Sept. 25 when you asked Prof. Hall to produce a written report, but indicated that the criminal justice system of British Columbia was bereft of any way to compensate Prof. Hall for such work. When Prof. Hall heard your instructions he and I went into private deliberations where he drew my attention to the funding issues in and around his involvement in the Fournier case.

[29] When we returned to open court on Sept. 25 you indicated extemporaneously from the Bench that you were aware of the centrality of funding issues in the genesis of the way Prof. Hall brought forward evidence in the Fournier matter. You indicated from the Bench that the report you were requiring 45 days before the commencement of the May 9-13 proceedings would not be onerous, that a single page would suffice. The memory of both Prof. Hall and I concur exactly on this key point. Certainly there was no mention on Sept. 25 of the new demands you are now making of my expert witness at the behest, it seems clear, of Rob Nicholson’s federal Crown prosecutor.

[30] Both Professor Hall and I took you at your word, Your Honour, that you are indeed aware of how it came to be that Prof. Hall took the stand in the Fournier matter without drafting a prior report. Prof. Hall was allowed, indeed encouraged by Judge O’Neill to take the stand equipped with a document camera to illustrate the documentary evidence as the expert witness began his evidence in chief. This process, taking 22 days of court time, has become somewhat legendary in some Aboriginal circles in Ontario. The majority of the time was taken up arguing over the admissibility of documents into the court record. As he did on the stand in the Chilliwack Law Courts on July 26 in spite of the BC Sheriffs’/RCMP smashing and pilfering of his box of evidence on July 25, Prof. Hall tried to equip himself with access to many documents so he could adapt on the spot to new knowledge of what the judge considered relevant or irrelevant. Prof. Hall tells me that about 90% of his documentary submissions was ultimately accepted.

[31] Neither Prof. Hall nor I expect the same kind of reception in the Chilliwack Law Courts on May 9-13 given the biases you have displayed, Your Honour, in making your conduct subservient to that of the federal Crown. The effect is that you and your provincial court give political cover to the Canadian government’s illegal policies that systematically deny and negate section 35. Your recent defense of Mr. Jensen’s personal conflict of interest makes it all the more clear who is really in charge of your very politicized provincial court.

[32] I am told that the digital projection of court evidence in North Bay in 2005 for court staff, but also for interested observers in the galley, helped advance the public education mandates that courts are theoretically supposed to promote in fostering good relations with the community.

[33] I would suggest, Your Honour, that your court has very poor relations with the Aboriginal community in BC. The response of the many Sto:lo citizens who gathered on July 26, 2012 in front of the Chilliwack Law Courts to protest the BC Sheriffs’ July 25 assault on my son and I for drumming and singing my new evidence into court speaks volumes. Why were so few of those gathered in front of the court hall willing to enter the building to witness for themselves what goes on in the KT trial? The answer is that your BC provincial court, Your Honour, is rightfully perceived by most of my people as a menacing and dangerous place where alien laws, rules, prohibitions, and punishments are meted out us often in arbitrary and coercive and violent ways. I would add, Your Honour, that Mr. Jensen has become in the eyes of many of my people, including Chief June Quipp, the very embodiment and personification of the federal Crown’s reign of terror masked under the guise of supposed law enforcement in the Hope/Chilliwack/ Fraser Canyon region.

Historical Background of Prof. Hall’s Role in the Fournier Case and the Linkages to the KT Case

[34] Prof. Hall’s involvement in what would become the Fournier matter actually started prior to the commencement of that trial in 2003. Several years before the Fournier case arose Ottawa lawyer Michael Swinwood travelled to Lethbridge to make a very specific request of Dr. Hall. Mr. Swinwood asked Prof. Hall for a short list of proposed constitutional questions pertaining to the Aboriginal peoples of Canada. Mr. Swinwood asked Prof. Hall to address his expertise to the most important issues facing the judiciary with special reference to section 35 of the Constitution Act, 1982 and section 25 of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms.

[35] Professor Hall produced such a list of constitutional questions. Mr. Swinwood would later bring forward a somewhat modified version of these questions in the legal proceedings that arose after Fournier, Menard, and Bergeron faced a number of criminal charges, including that of defrauding the public, for the distribution of membership cards in an organization known as the League of Indian Nations of North America. As Prof. Hall explained in the course of his 22 days on the stand in the Fournier matter, Jules Sioui, William Commanda and others founded this organization during the Second World War. This organization was established outside the web of federal legislation, policy, administration, and control centred on the Indian Act.

[36] Here is the ruling of Judge O’Neill given on Jan. 2004 when the federal-appointed jurist decided “it would be contrary to the interests of justice” for Prof. Hall’s constitutional questions not to be addressed in the Fournier matter. While I have brought forward the expert qualifications of Prof. Hall in Ontario Superior Court’s 2005 ruling, this is the first time I have introduced into the KT case Judge O’Neill’s 2004 ruling. Here is that ruling in its entirety.

R. v. Fournier, 2004 CanLII 66288 (ON SC)

| Date: | 2004-03-12 |

| Docket: | 012288 |

| Parallel citations: | 116 CRR (2d) 253 |

| URL: | http://canlii.ca/t/231vm |

| Citation: | R. v. Fournier, 2004 CanLII 66288 (ON SC), <http://canlii.ca/t/231vm> retrieved on 2013-04-21 |

| Share: | Share |

| Print: | PDF Format |

| Noteup: | Search for decisions citing this decision |

| Reflex Record | Related decisions, legislation cited and decisions cited |

Ontario Superior Court of Justice

R. v. Fournier

Date: 2004-03-12(No. 012288)

Brigitte Laplante, for respondent.

Michael Swinwood, for applicants.

O’neill J.:— A. Introduction [1] The applicants, along with Claude Bergeron, are jointly charged with offences contrary to ss. 369(b), 381(a) and 465(l)(c) of the Criminal Code, R.S.C. 1985, c. C-46. The alleged offences cover the time frame between February 1, 2001, and August 24, 2001, and involve the sale of alleged fraudulent native status cards.

[2] On July 29, 2003, counsel for the applicants filed a Notice of Constitutional Question seeking the following relief:

… the applicants intend to raise constitutional challenges to the inherent jurisdiction of the court to prosecute the applicants … to have declared that the provisions of the Indian ActSection 88 and 90 and the above section of the Criminal Codeof Canada are ultra vires the legislature of Canada and have declared unconstitutional as against these First Nations People and declared as no force or effect as against these Indian persons or any other Indian person. [sic]

[3] The hearing and argument with respect to the constitutional issue was scheduled for November 12, 2003, in North Bay, Ontario. On November 7, 2003, counsel for the applicants filed a notice seeking, in effect, an order adjourning the hearing of the constitutional question, pending a hearing at which state funding would be requested to advance the constitutional arguments. An adjournment was granted on November 12, 2003, and the arguing of the constitutional question was scheduled for January 28, 2004. In the interim it was expected that counsel would bring an application for court-ordered government funding.

[4] On January 28, 2004, the arguing of the constitutional question was converted into a motion for funding and payment of legal costs and expenses. There was filed, in relation to that hearing the following:

By the applicants:

(i) Notice of application and affidavit of Pierre Fournier sworn December 17, 2003.

(ii) Factum and Brief of Authorities.

By the respondent:

(i) Factum and Brief of Authorities.

[5] Counsel on the argument for funding agreed that the funding request was properly brought as against Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Ontario, and not the Attorney General of Canada. [5] When argument on the application was concluded, I reserved my decision, pending a review of possible further information from the Ontario Legal Aid Plan. Counsel for the applicant forwarded materials to Legal Aid Ontario and on March 4, 2004, he relayed to the court the tentative position of the Legal Aid Plan with respect to a payment of a portion of the costs requested by the applicants to fund the constitutional question. The materials filed and the evidence given at the January 28, 2004 hearing, the legal principles relating to the application, and the position of Legal Aid Ontario will be reviewed and dealt with in these reasons.

B. The Nature of the Charges Before the Court

[6] Count 2 on the indictment states that the applicants and Claude Bergeron conspired to commit the indictable offence of defrauding the public “by falsely representing that the League of Indian Nations of North America cards provide entitlements that do not exist”. Count 3 states that the applicants and Claude Bergeron did by deceit, falsehood, or other fraudulent means defraud the public of moneys exceeding $5,000 “by accepting fees for the sale of identification cards of the League of Indian Nations of North America and falsely representing these cards as conveying special status or privileges to the purchasers”.

[7] A copy of a card was entered as Exhibit 3 at the hearing on January 28, 2004. The front of the card states “UM 0317 INDIAN NATION OF NORTH AMERICA. This identification card indicates that Fournier Pierre is an Aboriginal person in terms of all Treaties and Covenants enrolled with Mohawk … The Sovereign Nation of INNA …”. The back of the card states, among other things: “…The INDIAN NATION OF NORTH AMERICA was reestablished in July 1945 and in 1991 to register Indian/Native persons, and to provide notice of Aboriginal RIGHTS and PRIVILEGES guaranteed to every Indian/Native person of North America. ABORIGINAL TREATY RIGHTS Granted to Indian, Inuit, Metis persons and those naturalized to live under the tutelage of sovereign Indian Nations and Governments…”.

[8] Various rights or entitlements are set out, in five paragraphs on the reverse portion of the card.

C. The Constitutional Question

[9] The grounds for the constitutional question, and the constitutional principles to be argued, are set out in the Notice of Constitutional Question dated July 29, 2003. Various statutory provisions, articles, books and legal authorities are also cited in the document. It is argued, among other grounds, that the federal government lacks proper legislative authority in the territory where the alleged illegal acts took place, that the territory is unceded Algonquin Nipissing First Nations Territory and that the establishment of law courts and enforcement officers in this territory is directly contrary to the Royal Proclamation of 1763. In paras. 4 and 5, under the heading The Constitutional Principles to be Argued, it is stated:

Para. 4 — That under the Constitution Act, 1982, section 7 “Everyone as [sic]the right to life, liberty and security of the person and the right not to be deprived thereof except in accordance with the principles of fundamental justice.” Section 11(d) adds that this includes the right to trial before “an independent and impartial tribunal.” Ever since 1704 it has been settled constitutional jurisdictional law that, in cases where the existence of Indian rights are in issue, the courts constituted by the competing newcomers arc constitutionally disqualified from adjudicating, on grounds of reasonable apprehension of bias at the institutional level. Based upon “principles of fundamental justice” the constitutionally designated “independent and impartial tribunal” is the one constituted by the Order in Council (Great Britain) of 9 March 1704 as the third party adjudicator. Upon the outcome of that third party adjudication turns the question of whether the Indian courts versus the newcomers’ courts have territorial jurisdiction vis-à-vis Indians in criminal matters. If Indian rights are found by the constitutionally designated third party adjudicator to have been purchased, the federal and provincial courts do have that jurisdiction. Until then, the natives’ own courts continue, as in Indian times, to have exclusive jurisdiction. That is what the injunction in the Royal Proclamation of 1763 that the Indians “should not be molested or disturbed” in relation to “such Lands as not having been ceded to or purchased by US” means.

Para. 5 – The Canadian Bill of Rights, 1960 also guarantees that “Affirming also that men and institutions remain free only when freedom is founded upon respect for moral and spiritual values and the rule of law,” the applicants invoke their right to pursue their spiritual values, embodied in the anishinabe tradition of asserting their sovereignty and freedom from levels of government which have invaded their territory and unilaterally imposed laws, when viewed through the prism of international law, render the Indian Act and the Criminal Code of Canada as inapplicable as against a member of the Indian First Nations.

D. The League of Indian Nations of North America

[10] In the affidavit of Pierre Fournier, sworn November 12, 2003, in support of the adjournment, it is set out, in paras. 2, 3, and 4 as follows:

2. I have been working with the League of Indian Nations of North America for the past 50 years and assert that it is a legitimate organization, with legitimate goals and objectives with a rich traditional history.

3. I speak on behalf of myself in these proceedings and assert that the Criminal Code charges against myself and the two others, puts into question the legitimacy of the existence of the League of Indian Nations of North America, and creates a contest between the State and (he League of Indian Nations of North America.

4. As evidence of the recognition of the legitimacy of the League of Indian Nations of North America, I attach as Exhibit “B” a copy of a letter issued from the International Parliament for Safety and Peace, located in Palermo, Italy, dated May 26th, 2003.

[11] In the further affidavit of Pierre Fournier sworn December 17, 2003, in support of the application for funding, there is attached to the affidavit Exhibit A — background paper on the historic “Amerikus League” and Exhibit B — the Legal Constitution of the Indian Nations of North America —June 8, 1944.

[12] In para. 10 of the affidavit, Mr. Fournier states:

The League of Indian Nations of North America is a legitimate organization, with legitimate goals for aboriginal people and the card that is produced for membership is simply a statement of legitimate aboriginal rights enshrined in the Constitution of Canada. The state has the wording of the card in their possession and I will produce my card at the hearing of the application to verify my claim to legitimacy herein.

[13] The constitution document consists of several paragraphs, explaining its purpose, including, in para. 5, the following:

The Authorities of the League of Indian Nations of North America shall he the guarantors of the integral respect of the legal rights. They shall endeavor to have all the treaties that were passed, respected and recognized, in order that the liberty and independence of the Indian Nations of North America he guaranteed.

There follows in the Exhibit B constitution, 12 enumerated articles.

E. Legal Principles Governing Applications for Funding

(i) Stay of proceedings — the Criminal Code context

[14] In R. v. Rowbotham 1988 CanLII 147 (ON CA), (1988), 35 C.R.R. 207, 41 C.C.C. (3d) 1 (Ont. C.A.), the Ontario Court of Appeal dealt with the issue as to whether an accused person has a constitutional right to be provided with counsel at the expense of the state. At p. 239 C.R.R., pp. 65-66 C.C.C, the court stated:

The right to retain counsel, constitutionally secured by s. 10(b) of the Charter, and the right to have counsel provided at the expense of the state are not the same thing. The Charter does not in terms constitutionalize the right of an indigent accused to be provided with funded counsel. At the advent of the Charter, legal aid systems were in force in the provinces, possessing the administrative machinery and trained personnel for determining whether an applicant for legal assistance lacked the means to pay counsel. In our opinion, those who framed the Charter did not expressly constitutionalize the right of an indigent accused to be provided with counsel, because they considered that, generally speaking, the provincial legal aid systems were adequate to provide counsel for persons charged with serious crimes who lacked the means to employ counsel. However, in cases not falling within provincial legal aid plans, ss. 7 and 11 (d) of the Charter, which guarantee an accused a fair trial in accordance with the principles of fundamental justice, require funded counsel to be provided if the accused wishes counsel, but cannot pay a lawyer, and representation of the accused by counsel is essential to a fair trial.

[15] By way of summary, the court stated, at pp. 243-44 C.R.R., p. 70 C.C.C. as follows:

To sum up: where the trial judge finds that representation of an accused by counsel is essential to a fair trial, the accused, as previously indicated, has a constitutional right to be provided with counsel at the expense of the state if he or she lacks the means to employ one. Where the trial judge is satisfied that an accused lacks the means to employ counsel, and that counsel is necessary to ensure a fair trial for the accused, a stay of the proceedings until funded counsel is provided is an appropriate remedy under s. 24(1) of the Charter where the prosecution insists on proceeding with the trial in breach of the accused’s Charter right to a fair trial. It is unnecessary in this case to decide whether the trial judge in those circumstances would also be empowered to direct that Legal Aid or the appropriate Attorney-General pay the fees of counsel.

[16] In the decision R. v. Rain 1998 ABCA 315 (CanLII), (1998), 56 C.R.R. (2d) 219, 130 C.C.C. (3d) 167 (Alta. C.A.), the Alberta Court of Appeal, at pp. 223-24 C.R.R., para. 7 C.C.C, outlined additional considerations for the court in relation to the issue of providing state-funded counsel in criminal matters:

… this court also indicated the type of evidence which would be useful for applications of this sort could include the financial circumstances of the accused, the accused’s educational background, what the accused knows of the charge, what particulars the accused has obtained from the Crown, what efforts were made to obtain legal aid, the reasons for legal aid’s denial, whether the accused has any other access to a lawyer or agent capable of giving her an effective defence to the charge and any other matter which would help the accused make her argument that she cannot fairly meet the charge without counsel.

[17] In the Rain decision, supra, the Alberta Court of Appeal indicated that the test which has evolved from Rowbotham has two aspects which must be considered (at p. 232 C.R.R.):

One is the accused’s circumstances. It must be determined if the accused can afford to retain counsel and if the accused has the education, experience and other abilities to conduct his or her own defence. The other is the nature of the charge or charges. Regard must be had to the seriousness of the offence, the complexity of the case and the length of trial. The central concern throughout is the fairness of the trial.

[18] In the decision United States of America v. Akrami, 2001 BCSC 165 (CanLII), [2001] B.C.J. No. 174 (QL), 2001 BCSC 165, Romilly J. outlined, at para. 32, the financial circumstances that an accused is required to demonstrate, as a prerequisite to an application for government funding of counsel:

… The Applicant must also show that he has made every attempt to apply for legal aid and, if initially denied, has exhausted all appeals available to him. If the proceedings have been before the Court for a lengthy period, it may be appropriate for the fugitive to re-apply for legal aid on the basis of a change in circumstances. In any event, he must make every attempt to obtain legal aid as the first precondition to the remedy sought.

(ii) Interim costs orders — British Columbia (Minister of Forests) v. Okanagan Indian Band

[19] On December 12, 2003, the Supreme Court of Canada handed down its decision in the above-noted case — 2003 SCC 71 (CanLII), [2003] 3 S.C.R. 371, 2003 SCC 71. At para. 36, LeBel J., for the majority, stated as follows:

There are several conditions that the case law identifies as relevant to the exercise of this power, all of which must be present for an interim costs order to be granted. The party seeking the order must be impecunious to the extent that, without such an order, that party would be deprived of the opportunity to proceed with the case. The claimant must establish a prima facie case of sufficient merit to warrant pursuit. And there must be special circumstances sufficient to satisfy the court that the case is within the narrow class of cases where this extraordinary exercise of its powers is appropriate. These requirements might be modified if the legislature were to set out the conditions on which interim costs are to be granted, or where courts develop criteria applicable to a particular situation where interim costs are authorized by statute (as is the case in relation to s. 249(4) of the Ontario Business Corporations Act; see Organ, supra, at p. 213). But in the usual case, where the court exercises its equitable jurisdiction to make such costs orders as it concludes are in the interests of justice, the three criteria of impecuniosity, a meritorious case and special circumstances must be established on the evidence before the court.

[20] Later, at para. 38, the Supreme Court dealt with the issue of interim costs in public interest litigation:

The present appeal raises the question of how the principles governing interim costs operate in combination with the special considerations that come into play in cases of public importance. In cases of this nature, as I have indicated above, the more usual purposes of costs awards are often superceded by other policy objectives, notably that of ensuring that ordinary citizens will have access to the courts to determine their constitutional rights and other issues of broad social significance. Furthermore, it is often inherent in the nature of cases of this kind that the issues to be determined are of significance not only to the parties but to the broader community, and as a result the public interest is served by a proper resolution of those issues.

[21] At para. 40 of its judgment, the court summarized the criteria that must be present to justify an award of interim costs in a case involving issues of public interest:

1. The party seeking interim costs genuinely cannot afford to pay for the litigation, and no other realistic option exists for bringing the issues to trial — in short, the litigation would be unable to proceed if the order were not made.

2. The claim to be adjudicated is prima facie meritorious; that is, the claim is at least a sufficient merit that it is contrary to the interest of justice for the opportunity to pursue the case to be forfeited just because the litigant lacks financial means.

3. The issues raised transcend the individual interests of a particular litigant, arc of public importance, and have not been resolved in previous cases.

[22] With these legal principles in mind, I now turn to a consideration of the funding application before me.

F. Analysis

(i) The financial issue

[23] Counsel for the applicants has estimated that the costs to fund the arguing of the constitutional question will amount to $35,000. These costs are set out in schedule C to a letter which counsel forwarded, with the court’s knowledge, to Legal Aid Ontario on February 17, 2004. The budget of $35,000, inclusive of travel, expert evidence, preparation and counsel fees, is fair and reasonable. This is especially so, given that the hearing will last between five and seven days, and the issues to be raised and dealt with are novel and complex.

[24] In court, Mr. Fournier indicated that he is the president of the League of Indian Nations of North America and that his only income at the present time is $1,016 monthly from old age security. Denise Menard receives a small monthly pension on account of a sickness or a disability. The applicants are not married but they live together and they share accommodations.

[25] Mr. Fournier explained that he receives $100 from applicants, and that he uses these funds to research aboriginal heritage and treaty status issues. Although $100 is paid by each applicant, Mr. Fournier can carry out research for entire families and ultimately cover off the costs and expenses of doing so.

[26] Mr. Fournier does not pay for a treasurer or a secretary, as Denise Menard carries out this work. Mr. Fournier indicated that by virtue of the present prosecution, the ability to raise funds through the League of Indian Nations of North America has been compromised.

[27] Under cross-examination, Mr. Fournier did confirm that in the Exhibit 2 document filed, the home page for the League of Indian Nations of North America, a message on the last page read: “…This program is established to create a trust fund to help pay for legal costs in aboriginal defence, including the present court battle of the League of Indian Nations or (sic) North America. All donations are appreciated…”. He stated that he was not aware of this request for donations and that he had no information that any money had been received as a result of this request.

[28] Mr. Fournier indicated that initially, he raised through his credit cards approximately $20,000 to pay for his original legal counsel. He stated that he was not able to defend himself, or present the constitutional question to the court and he felt that his counsel, Michael Swinwood, was the only one who was able to properly present the constitutional rights issue to the court. A school property in Quebec has been donated to LINNA, but the expenses to operate this property have become too expensive. In re-examination, Mr. Fournier indicated that LINNA received approximately $250 in donations in 2003, but as of January 4, 2004, there was an unpaid heating bill for the school property of approximately $7,000. Mr. Fournier confirmed that he still has money owing on his credit cards and that he owes $21,000 to CIBC bank, on account of a consolidation of his debts. He pays $550 monthly towards this loan consolidation.

[29] Pierre Fournier’s affidavit sworn December 17, 2003, and the oral evidence which he gave in court on January 28, 2004, satisfy me that the applicants simply do not have the financial means necessary to fund the constitutional question now filed with the court. I accept that there is little, if any equity in the property where the applicants reside and that they have exhausted their funds as a result of payments made to their original counsel.

(ii) The position of Legal Aid Ontario

[30] As indicated earlier in these reasons, the decision with respect to the application for funding was reserved, pending a review of possible information to be received from Legal Aid Ontario. On February 17, 2004, counsel for the applicants wrote to the plan and enclosed in his correspondence Schedule A, the indictment, Schedule B, the Notice of Constitutional Question, and Schedule C, the court budget of $35,000. The following questions were outlined in the letter:

Assuming that Mr. Fournier and Mrs. Menard could financially qualify for a Legal Aid Certificate would the Legal Aid Plan be able to accommodate a budget of $35,000 to advance by way of a defence the presentation of this Constitutional Question? Alternatively, what, if any budget would the Legal Aid Plan be able to provide in relation to the advance of these Constitutional Questions by way of a defence in the Criminal Code prosecution for this matter.

[31] On March 4, 2004, after receiving correspondence from the plan, and communicating directly with Mr. Thomas LeRoy, the Big Case Program Manager, counsel for the applicants advised the court of the following:

The hours outlined on the Schedule C budget were reasonable, from a Legal Aid perspective. The hourly rate if an application were approved, would amount to approximately $92.00 and experts’ fees would be paid at $100.00 per hour.

[32] Mr. LeRoy went on to indicate to Mr. Swinwood that if the applicants met the financial criteria, it would likely be recommended that one-half of the budget, or $17,500 be paid by Legal Aid Ontario to fund the constitutional question. Accordingly, Mr. Swinwood indicated to the court that he was prepared to reduce the amount that he was seeking directly from the respondent to the sum of $17,500, representing 50 per cent of the proposed Schedule C budget.

[33] I am satisfied from the evidence given and from the materials filed that even if Legal Aid Ontario funds one-half of the Schedule C budget, the applicants are nevertheless impecunious to the extent that they themselves are unable to fund or otherwise pay the remaining sum of $17,500.

(iii) A stay pending funding or an order requiring payment of legal fees and expenses in advance?

[34] Counsel for the respondent argued that in the context of a criminal prosecution, this court had no other alternative, if it determined that representation of the applicants by counsel was essential to a fair trial, and that the applicants lacked the means to employ counsel, but to stay the proceedings against the applicants until the necessary funding of counsel was provided. In short, counsel argued that the appropriate remedy was under s. 24(1) of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms, set out in Rowbotham, supra.

[35] I am not able to agree that having regard to the facts and circumstances of this case, and provided that all other prerequisites are met, a stay of proceedings is the appropriate remedy. While such a stay may be appropriate in traditional cases involving Criminal Codeprosecutions, it may not be appropriate in a case in which the principles outlined in the Okanagan case come into play, that is where: — the claim to be adjudicated is prima facie meritorious, and the issues raised transcend the individual interests of a particular litigant, are of public importance, and have not been resolved in previous cases.

[36] It is to be noted that in Okanagan, members of the four respondent Indian bands were served by the Minister of Forests with stop work orders under the Forests Practices Code of British Columbia Act, R.S.B.C. 1996, c. 159. Proceedings were instituted by the Minister to enforce these orders. The bands claimed that they had aboriginal title to the lands in question and that they were entitled to log them. They filed a notice of constitutional question challenging the code as conflicting with their constitutionally protected aboriginal rights.

[37] The B.C. Supreme Court remitted the case to the trial list rather than having it dealt with in a summary manner. The Supreme Court of Canada upheld this decision, but also found that in the circumstances of the case, the trial hearing ought to proceed but with an order for payment of interim legal costs. A stay of proceedings pending the funding of legal counsel was not ordered.

[38] Even though the applicants are accused persons in this case, and it is the Crown who has commenced criminal proceedings, in cases where:

(i) a notice of constitutional question is raised, by way of a defence,

(ii) the parties seeking costs are impecunious and no other realistic option exists for bringing the issues forward at a hearing,

(iii) the claim is at least of sufficient merit that it is contrary to the interests of justice for the opportunity to pursue the case to be forfeited because the applicants lack financial means, and

(iv) the issues raised transcend the individual interests of the particular accuseds, are of public importance and have not been resolved in previous cases,

(v) the more appropriate order, in my view, would be to require a payment of legal costs and disbursements, rather than to stay the proceedings pending the receipt of court ordered funding.

(iv) Is the claim to be adjudicated prima facie meritorious?

[39] Counsel for the applicants advised the court that in the words of Mr. LeRoy, “the issues raised in this case are important, significant and novel”. In his letter to Legal Aid Ontario dated February 17, 2004, counsel for the applicants summarized the defence which the applicants are seeking to establish in a hearing that will last between five and seven days:

i) The legitimacy of [sic]League of Indian Nation[s] of North American by virtue of the League mentioned in the indictment in count[s] #2 and #3.

ii) Sufficient evidentiary basis to raise a constitutional challenge to the inherent jurisdiction of the court to prosecute the applicants.

iii) To have declared s. 88 and s. 90 of the Indian Actand the above sections of the Criminal Code ultra vires of the legislation of Canada.

iv) To have declared these sections of the Indian Actand the Criminal Codeunconstitutional against these applicants and accordingly of no force or effect as against any other Indian person on the grounds as set out in the Notice of Constitutional Question (Schedule “B”).

[40] Counsel for the applicants intends to call Anthony J. Hall, Ph.D., from the University of Lethbridge, as well as two elders from Six Nations and from the Algonquin Nation. One of the articles or books referred to in the Notice of Constitutional Question is “Ethnic Cleansing and Genocide in North America and Kosovo” (May 17, 1999). The author is Dr. Anthony J. Hall. It is also submitted that Dr. Hall will be giving evidence in relation to the legal text which he has recently published entitled: The American Empire and the Fourth World (Montreal & Kingston: McGill-Queens University Press, 2003).

[41] Counsel for the applicants submits that one of the issues to be determined when the constitutional question is argued is whether the Department of Indian Affairs and Northern Development, as opposed to the League of Indian Nations of North America, is entitled to determine who is and is not an Indian, for the purpose of defining and delineating s. 35 constitutional rights. Counsel frames three additional questions to be determined as follows:

(i) Is the League of Indian Nations of North America a legitimate organization?

(ii) Are the statements which it makes on the card constitutionally correct?

(iii) Is the Department of Indian Affairs card superior to the LINNA card?

In my view there is sufficient information now filed with the court to suggest that in June of 1944, at a convention of Indian Chiefs held at Ottawa, the legal constitution for the Indian Nations of North America was reviewed and discussed.

[42] The deeper issue to be raised when the constitutional question is argued is whether, in the circumstances of this case, s. 91(24) of the Constitution Act, 1867and ss. 88 and 90 of the Indian Act, R.S.C. 1985, c. I-5, are applicable against an Indian person, and a member of an Indian nation, having regard to the affirmation and guarantee of s. 35 rights set out in the Constitution Act, 1982, and as measured against a claimed right of self-government and self-determination. It is to be noted that in Okanagan, supra, at para. 37, LeBel J. stated:

Although a litigant who requests interim costs must establish a case that is strong enough to get over the preliminary threshold of being worthy of pursuit, the order will not be refused merely because key issues remain live and contested between the parties.

[43] In my view, the constitutional questions to be raised at the proposed hearing, by way of a defence to the criminal charges, are clearly novel and complex. Counsel for the applicants has submitted that Dr. Hall will give evidence that through the prism of s. 35, aboriginal and treaty rights are to be given positive effect, and are not to be viewed in a manner which negates and denies the rights. The issues raised in the Notice of Constitutional Question are of sufficient merit that it would be contrary to the interests of justice for the opportunity to pursue these questions and these issues in this case to be forfeited if legal funding is not provided. It is to be remembered that the legal community in Canada is only beginning to come to grips with issues involving aboriginal title and rights. Indeed, in R. v. Sparrow, 1990 CanLII 104 (SCC), [1990] 1 S.C.R. 1075, 56 C.C.C. (3d) 263, Dickson C.J.C. and LaForest J. stated, at p. 283 C.C.C. as follows:

For many years, the rights of the Indians to their aboriginal lands — certainly as legal rights — were virtually ignored. The leading cases defining Indian rights in the early part of the century were directed at claims supported by the Royal Proclamation or other legal instruments, and even these cases were essentially concerned with settling legislative jurisdiction or the rights of commercial enterprises. For 50 years after the publication of Clement’s The Law of the Canadian Constitution, 3rd ed. (1916), there was a virtual absence of discussion of any kind of Indian rights to land even in academic literature. By the late 1960s, aboriginal claims were not even recognized by the federal government as having any legal status.

[44] Later, at p.285C.C.C, they stated:

It is clear, then, that s. 35(1) of the Constitution Act, 1982, represents the culmination of a long and difficult struggle in both the political forum and the courts for the constitutional recognition of aboriginal rights. …

In our opinion, (the significance of s. 35(1) extends beyond these fundamental effects. Professor Lyon in “An Essay on Constitutional Interpretation” (1988), 26 Osgoode Hall L.J. 95, says the following about s. 35(1), at p. 100:

… the context of 1982 is surely enough to tell us that this is not just a codification of the case law on aboriginal rights that had accumulated by 1982. Section 35 calls for a just settlement for aboriginal peoples. It renounces the old rules of the game under which the Crown established courts of law and denied those courts the authority to question sovereign claims made by the Crown.

(v) Do the issues raised transcend the individual interests of the applicants, are they of public importance and have they been resolved in previous cases’?

[45] The jurisdiction and authority of this court is in question, as set out in the Notice of Constitutional Question filed. The question of jurisdiction and authority is an important one, because Canada operates under the rule of law, as set out in the Constitution Act, 1982. The authority of this court to deal with the charges against the applicants is a question that must be answered, not only for these applicants, but likely for other litigants, claimants, defendants and accused persons as well.

[46] It is obvious that the questions raised in the Notice of Constitutional Question transcend the individual interests of the applicants. The answers to the issues raised may determine whether ss. 88 and 90 of the Indian Actare applicable to other Indian persons, and whether in cases similar to this, where it is alleged that a prosecution is taking place in unceded Indian territory, federal and provincial courts have jurisdiction in criminal matters relating to Indians. The issues raised in the Notice, involving the Royal Proclamation of 1763, the applicability of s. 91(24) of the Constitution Act, 1867and ss. 88 and 90 of the Indian Act, are clearly of public importance and have not been directly resolved in previous cases. These issues meet criteria number 3 set out, in para. 40 of the Okanagan case, supra.

[47] In concluding that an award of interim costs is justified in this criminal case, I also bear in mind that post-Okanagan, the following issue raised in Rowbotham, supra, at p. 244 C.R.R., p. 70 C.C.C., has now been answered:

… whether the trial judge in those circumstances would also be empowered to direct that Legal Aid or the appropriate Attorney General pay the fees of counsel.

G. Conclusion

[48] For the reasons herein given, an order is made that Her Majesty the Queen in Right of the Province of Ontario, shall forthwith make payment to the applicants’ counsel, of the sum of $17,500, to be utilized by counsel to advance and argue the constitutional questions outlined in the Notice of Constitutional Question dated July 29, 2003. The sum of $17,500 shall be utilized by counsel for those expenses and costs outlined in Schedule C to the letter of February 17, 2004, but without prejudice to the applicants’ counsel to seek up to an identical amount from Legal Aid Ontario in order to fund the remaining costs, if necessary, of the application. Counsel shall file with the court, upon completion of the arguing of the constitutional question, a report documenting the expenditure of these moneys in a manner consistent with Schedule c. Any surplus funds not utilized for this process shall be returned to the respondent at the conclusion of the hearing.

[49] The respondent shall pay to the applicants their costs of this application, which I hereby fix in the sum of $2,500. Order accordingly.

Motion granted.

http://www.canlii.org/en/on/onsc/doc/2004/2004canlii66288/2004canlii66288.html

[37] Obviously Judge O’Neill took a very different view of the meaning of the Rowbotham matter than did you, Your Honour. Judge O’Neill also took a very different view of Rowbotham matter than did The Hon. Rob Nicholson’s agent, Mr. Finn Jensen, or Mr. Jensen’s colleague and expert witness, Mr James Whiting. The O’Neill ruling in 2004 clarifies the roots of the contention brought forward in the KT case that “through the prism of s. 35, aboriginal and treaty rights are to be given positive effect, and are not to be viewed in a manner which negates and denies the rights.” Judge O’Neill was outspoken in his contention that “The issues raised in the Notice of Constitutional Question are of sufficient merit that it would be contrary to the interests of justice for the opportunity to pursue these questions and these issues in this case to be forfeited if legal funding is not provided.” Is it any less contrary to the interests of justice, Your Honour, how you and Mr Jensen have joined together in the effort to block the obtaining of resources for juridical consideration in your provincial court of the serious constitutional questions that arise from the charge against me for illegally possessing fish?

[38] I believe Judge O’Neill was dismayed when the Crown of Ontario decided to appeal his ruling that funding should be provided for Prof. Hall to prepare a report wherein he would have documented his thinking with supporting evidence that led him to formulate the constitutional questions put forward by Mr. Swinwood in the Fournier matter. In response to the provincial Crown’s appeal to a higher court, Judge O’Neill through Mr. Swinwood requested Prof. Hall’s attendance in federal court in North Bay Ontario.

[39] Prof. Hall’s formal involvement in the Fournier matter began with two-and-a half days of hearings to establish the basis and extent of Prof. Hall’s expertise. In the course of these proceedings arose the broad statement of Prof. Hall’s court-recognized area of expertise replicated with some slight modification by you, Your Honour. These proceedings led to Prof. Hall taking the stand to lay out the case behind his constitutional questions. It is important to understand that Prof. Hall took the stand without producing a prior written report. Prof. Hall made it clear he would not work on such a report without some compensation. Judge O’Neill made sure that Prof. Hall was provided on the stand in the federal court at North Bay court with a document camera and digital projector to help him document his case as presented it from the stand.

[40] This history provides the background of Prof. Hall’s response put forward in your provincial court through me when you asked the Lethbridge academic on September 25 to produce a written report in spite of the fact he is not being compensated even for travel, food and accommodation expenses let alone for his contribution of expert knowledge and intellectual property to the court. What does it say that my defence has to be run as a charity for Canada even as those conducting the criminalization of me have wide access to the deep pockets of the federal government to advance the federal Crown’s prosecution as well as its persecution in your provincial court.

The MacDonald Estate case as a Diversion to Draw Attention Away from the Fiduciary Responsibilities of the Federal Crown to the Aboriginal Peoples of Canada

[41] As Prof. Hall and I increasingly see it, both levels of government in our federal state experience conflicts of interest when it comes to their obligation to represent all the people of Canada on the one hand and, on the other, to act as a trustee of the remaining Aboriginal estate of the Aboriginal peoples of Canada. It is the Aboriginal peoples of Canada that consistently lose out when the government must choose between winning approval from the wider Canadian population at the ballot box and living up to the rule of law when it comes to the application and enforcement of section 35.

[42] I believe Prof. Hall felt himself to be at an extreme disadvantage in producing his report of March 26. This disadvantage arose because he did not know your verdict on the conflict-of-interest involving Mr. Jensen in the first instance with the deeper background of the Canadian state’s conflict-of-interest especially in circumstances of litigation such as the one in which we are currently engaged. The inequity of this process, as now expressed in your new demands of the unresourced and unlawyered defense, can become simply overwhelming at times. We are at one of those times in this manifestly unfair trial permeated with conflict-of-interest that goes far beyond anything addressed in the MacDonald Estate case.

[43] I have never been shown nor have I ever read myself the MacDonald Estate case to which you made no reference in the January 14 proceedings. Why did not you or your office send me a copy of it? On April 19 you cut me off when I tried to raise the issues of your irrelevancies in your judicial defense of Mr. Jensen’s conflict of interest. I am asking now if your reference in your most recent ruling to the MacDonald Estate case was intended as a sick joke at my expense to rub salt into the wound that I am unrepresented in this trial where solicitor-client confidentiality is absolutely irrelevant. The core of your ruling in defense of Mr. Jensen’s conflict of interest has no direct bearing on the circumstances of the constitutional phase of this unfair trial.

[44] What has the MacDonald Estate case got to with Aboriginal fishing on the Fraser River or with section 35 or with the fiduciary responsibilities of the federal Crown to the Aboriginal peoples of Canada? When did I ever claim that Mr. Jensen was privy to some sort of insider knowledge derived improperly my non-existent solicitor-client relationship? Why did you ignore and misrepresent the evidence that I brought forward on this matter? Why are still stonewall me when it come to dealing with the core constitutional questions I have been raising? Why did you deviate so far from the constitutional questions put before you beginning with my leading the evidence at this stage of the trial with my November 23 notarized letter and its subsequent refinements and amplifications?

[45] As I see it, Your Honour, your telling resort to the MacDonald Estate case to defend Mr. Jensen’s conflict of interest as well as the institutional conflict of interest of Rob Nicholson and his federal Ministry of Justice epitomizes the farce and injustice of a law enforcement establishment that has gone off the rails. Our main function as Aboriginal peoples in Canada’s bloated criminal justice system has become to serve as a cash cow for political patronage payments to lawyers on the take and as a huge and parasitical make-work-project for thousands of officials right across Canada, officials like you, Your Honour, and private contractor Finn Jensen.

[46] Moreover, why do you add new insult to old injuries in this proceeding premised since the Crown’s illegal selling of my fish on the principle that I am guilty until proven innocent? Your Honour, you and Mr. Jensen extended consideration of the regulatory aspects of this matter from July of 2004 to July of 2012 without seriously addressing the section 35 arguments, arguments adamantly brought forward by me from the moment DFO officials stolen my fish at the commercial establishment of Mr. Mike Denike. Now I learn from one of your asides in the April 19 tele-court proceedings that the main constitutional subject I want to address at this stage of the trial, namely the 35 infringements of section 35, you intend to leave for “the end of the trial.” Now that is a biased court!

[47] The absurdity of your judicial treatment of our Aboriginal and treaty rights as some function of the MacDonald Estate case well encapsulates that this trial, which is manifestly mismanaged and in the wrong jurisdiction, is approaching an impasse. I have an equal voice with that of Mr. Jensen and in this trial and at this stage of the proceedings, when I am leading the evidence as an unrepresented defendant. With this assertion that I have a say in this trial equal to that of the Ministry of Justice’s private contractor I demand that my 35 alleged infringements of section 35 must be addressed in a timely fashion. A number of these infringements have to do in whole or in part with actions taken and decisions made by you and Mr. Jensen. I refuse to accept an empty promise that these federal infringements will be dealt with at some point in the distant future? I demand the federal infringements be addressed near the beginning rather than at the end of this constitutional stage of this trial. Since November 23, Your Honour, you and Mr. Jensen have been put on notice that I have invoked my Sparrow case right and responsibility to demand justifications for the very serious federal infringements of section 35. I refuse to tolerate any more judicial chicanery to lead away for from my core constitutional questions as you did by invoking the MacDonald Estate case to defend Mr. Jensen’s conflict of interest.

[48] Was I facing some tactic of psychological warfare from you and Mr. Jensen in the tele-court proceedings of April 19? How am I supposed to respond to news of your invented pre-trial procedures for establishing evidentiary relevance conveyed to me only three days after I received your most ruling one month late. The Crabtree ruling of April 3, or April 5, or April 9, or April 16 provides an exemplary illustration of the deployment of irrelevance to avoid facing all of the substantive issues concerning the many conflicts-of-interest that permeate all aspects of Crown involvement in this unfair trial and others of its type. Why are both you and Mr. Jensen so consistently deaf and dumb especially when it comes to the Crown’s fiduciary responsibilities you both consistently deny and negate, seemingly with no accountability whatsoever?

Next Steps?

[49] As I understand it Prof. Hall is trying to resolve himself to the new demands on his time, resources and expertise. He seems to agree with me that those conducting these proceedings, from the presiding Judge, to the federal Crown prosecutor, to the staff of the court registry, to the BC sheriffs, to the RCMP investigators of the July 25 event, just make up the rules in a constantly changing fashion as the proceedings move along. As I understand it Prof. Hall refuses to submit a list of documents without some provision to argue out the relevance of each document and each theme of inquiry in an appropriate fashion and in an appropriate venue.

[50] As I understand it, Prof. Hall is trying to rally himself to come up with a second report to explain in more detail what he intends to cover as well as the nature and details of the relevant evidence he intends to bring forward to advance his interpretations. If you insist on continuing to deviate arbitrarily from the Fournier precedents my understanding is that the expert witness believes you are leaving him with no choice but to address the question of relevance simultaneously with the production of the document list.

[51] For your information I see Prof. Hall preparing for the May 9-13 session with a wide array of sources, some of which are familiar to me and some of which are not. Recall, Your Honour, that Prof. Hall is an historian, not a lawyer. He does not come from the same professional culture as you and Mr. Jensen. Why not afford some latitude to see if Prof. Hall can in the next few days, but especially after he submits the final grades of his students, produce something prior to the trial that will satisfy you and Mr. Jensen as well as his own sense of professionalism under these trying circumstances?