by Anthony J Hall

From the Royal Proclamation of 1763, to the American Declaration of Independence, to the Indian Act, to Dan George and Canada’s Centennial Year, to the White Paper of 1969, to Section 35 and Canada’s constitutional Recognition and Affirmation of Aboriginal and Treaty Rights, to Idle No More, to the Case of Kwitsel Tatel: Explorations in the Contextualization of History

Dan George as an Icon of Aboriginal Resistance. Dan George as Law Giver.

It is Boxing Day, 2012, as I begin this essay introducing Dan George’s speech at the Vancouver Coliseum on July 1st, 1967, the day billed as the main birthday celebration of Canada’s Centennial Year. By highlighting a First Nations perspective on law and legitimacy I seek to draw a contrast with the jurisprudence of the Supreme Court of Canada as articulated, for instance, in its rulings on the Sparrow and Van der Peet cases.

Dan George’s words have particular poignancy in this context because he was the head of the family that adopted Kwitsel Tatel after she was orphaned at the age of thirteen. I have been publishing in Veteran’s Today a running report on the case of Kwitsel Tatel, a proceeding that resumes in the Law Courts of Chilliwack British Columbia on January 14. Many of the major arguments being brought forward in this case of Kwitsel Tatel, which began in 2004, add background and depth to the major contentions of the Idle No More movement.

To this day Kwitsel Tatel, whose Christian name is Patricia Kelly, still refers to Dan George as “grandpa.” She often speaks, for instance, of her grandpa’s all-night guitar strumming sessions. These sessions were sometimes interspersed with avid political debates, as happened when the Shuswap scholar and sage of the Fourth World, George Manuel, dropped by for a festive visit.[1]

A stage and screen actor of considerable accomplishment, Dan George would become in the 1970s one of the most recognizable Indian men in North America. This Coast Salish actor from the Vancouver area received an Oscar nomination after co-starring with Dustin Hoffman in Arthur Penn’s blockbuster Hollywood hit, Little Big Man. The movie perfectly captured the changing attitudes of the times in an era when old orthodoxies began to break down.

As Dan George moved into the spotlight of popular attention, public opinion was turning hostile towards, for example, the US military intervention in Vietnam. Changing perceptions on the expansionary character of US wars of aggression in southeast Asia tended to alter attitudes about many things, including the place of the Indian wars in US history.[2] As a Hollywood icon embodying the downtrodden but indomitable spirit of Aboriginal America, Dan George adeptly used his celebrity to challenge power and alter public consciousness. His main theme was the contemporary dilemmas arising from the oppression of Indigenous peoples under the weight of a North American society engineered primarily to serve the needs and wants of immigrants and their descendants.

- Chief Dan George, Native American Icon, Native American Law Giver

Something New and Something Old,

Idle No More in Historical Context

I embark on this project as a new year is about to dawn. As I write, momentous events are underway with major implication for the relationship between the Canadian state and the Aboriginal peoples of Canada. These events give contemporary context and resonance to the historical processes I want to highlight. As in the era of Canada’s Centennial celebrations, the contemporary stirrings of Indigenous peoples are once again beginning to capture the attention of an aroused and restive public. The ideas and imagery of Idle No More have spilled into many venues including the byways of commerce in shopping malls across Canada and in similar installations in the United States.[3]

For short periods of time the businesses in these citadels of consumerism come to a standstill as assemblies of drummers, singers, and round dancers burst into expressive celebration. Sometimes the round dances are accompanied by sit-ins and brief blockades of road or railway thoroughfares. The emphasis on drumming, singing, and dancing invokes memories of the long period in Canadian history ending in 1951 when the Parliament of Canada made it illegal for Indian people to take part in such activities.

During the era when Canada outlawed overt expressions of Aboriginal spirituality, prairie sun dancing or West Coast potlatching were treated as retrogressive deviations leading away from the assimilationist project led by Christian missionaries empowered through federal funding of their Indian residential schools. The round dancing of Idle No More has been bursting forth in places big and small, from Vancouver, to Lethbridge, to Regina, Winnipeg, Edmonton, Brantford, Ottawa, Cornwall, and Toronto to mention only a few. One of the largest displays took place in the massive Mall of America in Minneapolis Minnesota, the metropolis from which the American Indian Movement arose to prominence in the early 1970s. From Hawaii, to Columbia, to Washington DC, to the Palestinian Diaspora, support events have rapidly proliferated. All over the world those who have suffered the incursions of colonization, by far the largest portion of humanity, can easily identify with the transformation of Native Americans into marginalized underclasses in their own Aboriginal territories.

These celebratory displays of Aboriginal affirmation resonate with some of the same energy that must have permeated the circle dancing that swept through the remaining Indian Country of the North American mid-west in 1890.[4] Some have compared the circle dancing phenomena of 1890 with the contemporaneous so-called Boxer Rebellion of Chinese patriots who opposed through direct action the onslaughts of European imperialism in their mother country.

In Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee Dee Brown famously captured literary snapshots of this time of transition in what former US president Theodore Roosevelt tellingly described in his ethnocentric history texts as The Winning of the West.[5] As Brown explained, in 1890 the era of systematic military suppression of Aboriginal peoples culminated in the US Armed Forces’ massacre of Big Foot’s band at Wounded Knee in South Dakota. The US soldiers killing spree of largely unarmed elders, women and children was meant as revenge for the Aboriginal defeat of Colonel George Armstrong Custer’s Seventh Cavalry division at the Battle of Little Bighorn in 1876.

- Buffy Sainte-Marie Singing Her ballad, Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee. In 1973 the American Indian Movement took sovereign control of land at Wounded Knee, the site of the Seventh Cavalry’s revenge killing of Big Foot’s band. AIM’s stance was met with the intervention of the US Armed Forces. To this day Leonard Peltier is a political prisoner in US penitentiary. Peltier was framed, first in Canada and then in the United States, to advance the FBI’s War on AIM. The Seventh Cavalry committed the massacre in 1890 as revenge for the Aboriginal defeat of Colonel George Armstrong Custer’s unit at the Battle of Little Bighorn in 1876. This historical and contemporary milieu formed the stuff of Buffy’s extremely popular repertoire of her own folk music. Truly Buffy Sainte-Marie is a powerful writer, arranger, and performer of anthems advocating rights and dignity for Native Americans and humanity in general. Buffy has proudly held up the musical assertions of Red Power with style and verve for many decades. She has long reigned her field.

This pivotal display of massive military superiority and the willingness to deploy it unrelentingly signaled the shift that saw the targeted First Nations tightly contained within the confines of reserves and within the special laws and bureaucracies treating registered Indians in both Canada and the United States as the disenfranchised wards of federal authority. The circle dancing of 1890 signaled that many Native North Americans would not succumb to the assimilationist policies of their colonizers. They would do what was necessary to adapt outwardly to the conventions of their oppressors even as they would hold tenaciously to remnants of their own Aboriginal inheritances of culture and spirituality.

This Fourth World resistance to the hostile incursions of colonization speaks of key facets of indigenous self-determination. It is the same spirit of resistance that inspires the Idle No More movement. It is the same spirit of decolonization that ignited the flame of human dignity as expressed in the initial phases of the Arab Spring movement, especially as it took hold in the massive and disciplined displays of citizens’ solidarity in Cairo’s Tahrir Square. The round dancers of Idle No More demonstrate the same attitudes of noncompliance with bankers’ tyranny that spread to the Indignados of Europe and then gave rise to the international reach of the Occupy Wall Street movement.

Idle to More builds on the blossoming in Quebec of the Maple Spring movement. In the spring and summer of 2012 Quebec citizens took to the streets proclaiming their identity as makers of Le printemps érable—the Maple Spring. In flexing their muscles they changed the provincial government in North America’s primary French-speaking jurisdiction. They cultivated, nurtured and directed popular opposition to the top-down cult of “austerity.” Like the Maple Spring, the Idle No More movement combines targeted criticisms of particular policies with more general analysis of the prevailing political economy of ecological and social mayhem. The Maple Spring movement and the Idle No More movement converge in the importance placed on universal access to post-secondary education as a basic right of citizenship.

The Idle No More movement began in a series of information gatherings organized in late November of 2012 in the Saskatoon-Prince Albert-Regina area of the Canadian province of Saskatchewan. The organizers included Jess Gordon, Nina Wilson, Sheelah Mclean, and Sylvia McAdam. While the list of inter-related topics addressed was wide ranging, the core of the initial critique was the content of the so-called Omnibus Bill, C-45, a sweeping expression of Prime Minister Stephen Harper’s zeal to bring about dramatic transformations in some of the core structures of Canadian federalism.

A group calling itself Lawyers’ Rights Watch has described the anti-democratic character of C-45 as follows:

Protests have been triggered by Bill C-45, which violates the rule of law as it has traditionally been defined through the democratization movement of the 19th and 20th centuries. Lumping together more than 550 provisions on more than 30 topics in a 443 page omnibus bill foreclosed the open public discussion and consultation that are essential according to both the Canadian constitution and the internationally defined democratic standard of prior informed consent. As such, the manner in which Bill C-45 was presented and passed fails to measure up to Canadian or international standards.[6]

Stephen Harper, who once advocated putting a “fire wall” around the legislative powers of Alberta, seeks with his ambitious legislative agenda to diminish the role of the national government. Harper wants to hand over federal powers to provincial governments, deregulate the national economy to facilitate the enhanced commercial traction of transnational corporations, and remove federal and Aboriginal obstacles to environmentally-menacing projects like the Northern Gateway pipeline and Kinder Morgan pipeline expansion. Both proposed projects point across the mountains and valleys of British Columbia.

In order to advance this agenda, Bill C-45 includes provisions that withdraw the federal government from much of its responsibilities to protect navigable waters, to protect fish habitat throughout the many millions of swamps, creeks, rivers and lakes that are so integral to Canada’s Aboriginal geography and natural heritage. Harper is taking much of his lead from Professor Tom Flanagan, a US-educated political scientist who sought to replace the more moderate agendas of the Canadian Progressive Conservative Party with the more radical tactics and philosophy of Reagan Revolution in the United States. Borrowing wholesale from Flanagan’s inflammatory text, which characterized the Indigenous peoples of Canada as an earlier class of immigrant, Harper seeks to continue the privatization and municipalization of the Indian reserves that still adhere to Canada’s 640 or so Indian bands. Collectively all of Canada’s Indian reserves cover about ½ of 1% of Canada’s enormous land mass.[7]

Harper’s termination policies run contrary to that facet of the rule of law that has its centre of gravity in the deceptively simple wording of the constitutional provision that resides at the very core of the case that has been dubbed The Queen and Kwitsel Tatel versus the Government of Canada. Section 35 of Canada’s Constitution Act, 1982, proclaims that “the existing Aboriginal and treaty rights of the Aboriginal peoples of Canada are hereby recognized and affirmed.” Some Aboriginal peoples in Canada are parties to the ninety or so treaties mostly with the British imperial sovereign. Others, such as those First Nation communities throughout most of British Columbia, are living on territories where the Aboriginal title remains uncompromised in any way. In much of British Columbia the requirements of the Royal Proclamation’s Indian provisions have never been met.[8]

These provisions require the Crown officers to obtain Aboriginal consent for the expansion of non-Aboriginal settlements. The result is that Canada’s westernmost province has developed outside the rule of law—imperial law, constitutional law, international law and national law. This lapse is slowly being addressed, however problematically, in the establishment of about 60 tables for Crown-Aboriginal treaty negotiations covering much of British Columbia. These so-called negotiations, however, are being sapped of substance by Crown criminal proceedings such as those directed at Kwitsel Tatel and other Aboriginal individuals in similar positions. Such criminal proceedings led by Crown prosecutors assume the outcome of negotiations before the terms of agreement are actually reached. The charges against Kwitsel Tatel signal that Crown officials representing the two levels of federal government involved in the litigation do not acknowledge the true nature of their unsound legal positions in treaty talks with the First Nations of British Columbia. Crown officials jump the gun by using the criminal courts to assert powers and jurisdictions that should be the subject of reciprocal give and take rather than unilateral assertions of authority based on nothing more than the presumption that might makes right.

By invoking the rights and titles and treaties with the Crown of all the Aboriginal peoples of Canada, section 35 helps to transcend legal distinctions that for far too long have been exploited in the ongoing renewal of divide-and-conquer strategies. As the main body of Kwitsel Tatel’s letter to Judge Thomas Crabtree should make abundantly clear, those Aboriginal peoples with treaties and those without treaties face a common onslaught of federal hostility from Stephen Harper’s so-called Ministry of Justice whenever Aboriginal and treaty rights are made subject to judicial arbitration in court. What the Supreme Court of Canada has referred to as “the honour of the Crown” has consistently been besmirched because federal lawyers representing the Queen of Canada consistently take positions in court that deny and negate rather than recognize and affirm the existence of Aboriginal and treaty rights as federal Crown officials are legally required to do.

This effort to undermine and diminish the federal and Aboriginal aspect of Canada according to imported models of divide-and-conquer neoliberalism repeats some of the same assimilationist themes attempted by the Liberal government of Prime Minister Pierre Elliot Trudeau with his notorious White Paper on federal Indian policy in 1969.[9] My impression is that the Aboriginal rejection of Bill C-45 and all it portends for Canada’s future has far more depth in the grass roots of Indian Country than did the Indian rejection of Pierre Trudeau’s and Jean Chretien’s White Paper policy of 1969. Where the latter was largely led by the federally-funded chiefs that drew their authority primarily from the federally-legislated Indian Act, Idle No More is mobilizing a more diverse constituency with spokespeople that tend to be disproportionately female.

The rapid spread of Idle No More’s contentions into, for instance, trade unionism, the Israel-Palestine question, and the assertions of indigenismo in Latin America, make it clear that the movement’s emerging leadership holds the capacity to engender extensive networks of alliance, domestic and transnational. As I write these words alliances are cutting across many sectors of civil society. From its Aboriginal base the movement as presently constituted seems to be becoming an effective conduit for more general opposition to Stephen Harper’s radical and polarizing policies. Indeed, the very legitimacy of Harper’s mandate is unclear. Ongoing revelations about widespread cheating in the Conservative Party’s capturing of a majority of seats in the Canadian House of Commons has left the Harper group with a tainted mandate.[10]

Attawapiskat as a Marker of Failed Aboriginal Policies in Canada

Chief Theresa Spence gave a clear centre of gravity to the initial phase of the Idle No More movement. The elected chief of the Attawapiskat reserve on the western shores of James Bay, Chief Spence began on December 11 a principled pilgrimage into hunger and want. Chief Spence’s ritual of self-sacrifice through fasting is, as I write, taking place in a teepee on Victoria Island in the Ottawa River just across from Parliament Hill. My son Sampson was able to visit Chief Spence personally on Christmas Day.

As I write, the Chief of Attawapiskat will join a group of fellow chiefs elected by the terms of the Canadian Indian Act to meet with Canadian Prime Minister Stephen Harper and a representative of Queen Elizabeth II in Her capacity as the primary trustee of the Aboriginal and treaty rights of the Aboriginal peoples of Canada. Historically the Queen’s ancestors invested the royal family with the ultimate responsibility for upholding the Crown’s side of treaty agreements with the Aboriginal peoples of Canada. Unfortunately, the heavily-politicized Governor-General’s Office has little remaining credibility among First Nations or many other discerning Canadians. The Office of the Queen’s representative in Canada was severely sabotaged in 2008-2009 when Prime Minister Harper bludgeoned the Queen’s Representative in Canada who illegally adjourned Parliament just as he was about to lose a confidence vote and thereby open the way for the leaders of other parties to form a majoritarian coalition.

The very setup of this meeting of January 11, 2013 brings out into the open the growing divide between those individuals and family voting cliques who work within the Indian Act system and those grass-roots community activists in Indian Country who have put at the forefront their unwillingness to comply any longer with a system of institutional assimilation that inherently denies and negates section 35. This long-developing schism promises to ignite a serious national debate on the Indian Act and the representation structure of the Assembly of First Nations, an association composed of Canada’s 650 elected chiefs chosen according to the provision of the Canadian parliament’s Indian Act. These Indian Act chiefs maintain their monopolization over the process of electing the AFN’s National Chief. The National Chief’s very narrow constituency of electors seriously limits the representational effectiveness of Canada’s most high-profile Aboriginal organization. This lack of effectiveness was put on clear display in 1992 in the national referendum on a proposed constitutional amendment. This amendment failed to receive voter support on most Indian reserves in spite of the fact that so many provisions were negotiated with the direct involvement of AFN National Chief, Ovide Mercredi.

An ancient staple of Chief Spence’s home community is geese. Geese and wild rice make up an abundant renewable resource that has long fed the Muskego Crees in the swampy borderlands of Canada’s arctic tundra. The richness of the indigenous food sources on the shores of James and Hudson’s Bays has been matched in every Aboriginal territory across the land. For instance seafood formed, and in some cases still forms, the main staple along Canada’s coastal waters whereas corns, beans and squash gave the people of Iroquoia their main sustenance in what is now southern Ontario and the St. Lawrence Valley. Across the prairies buffalo offered the two-leggeds an incredibly prolific means of earning livelihoods. On the Canadian Shield a cornucopia of wild mammals, fish, berries, together with the produce of small Aboriginal gardens kept the people strong and healthy. The natural medicines of herbs, clean water, clean air, pure foods, and rich weavings of interpersonal, intergenerational, and interspecies relationships thrived, offering all that was needed for good mental health as well as hardy physical health.

Through the agency of federal control, however, Indian people have been largely stripped from their Aboriginal lands and waters and stripped from their Aboriginal polities, belief systems, and lifeways. In the process many Indian communities in Canada were transformed from sites of thriving wellbeing into gateways leading to hell on Earth. As with too many of Canada’s Indian reserves, plagues of homelessness, malnutrition, addictions, unemployment, medical malfeasance, and domestic violence have been allowed to rage throughout Attawapiskat’s imperiled population.

The festering of these lethal conditions at Attawapiskat and on many other Indian reserves and urban ghettos stand as markers of despair that rightfully hold Canada up to international infamy. Such disfiguring wounds in our blighted body politic shames a resource-rich country that has made a small minority very rich from the industrial-scale exploitation of nature’s Aboriginal bounty. The result is that swelling millions of critics the world over are pointing fingers of sharp condemnation at Canada’s federal government. The evidence is mounting that the federal government is quickening the pace of its violations of fundamental human rights through the rapid acceleration of its notorious regime of dispossession and subjugation of the country’s original inhabitants, the First Nations of Canada.

One of the systemic problems is that the scope of the rights and titles of Aboriginal peoples is almost never subjected to genuine third-party adjudication when assertions of Aboriginal sovereignty and ownership of resources come up in court. In Canada judges owe their appointments to federal and provincial politicians even as they frequently own land title and draw paychecks that depend on maintaining the status quo in the jurisdictions where they and their families reside. As a rule, therefore, Canadian judges are not in a position to render genuinely disinterested verdicts on Aboriginal matters because they have large personal stakes in the very issues they must decide. This bias puts the whole judiciary in positions of institutionalized conflict of interest. This dilemma is not unique to Canada. Indigenous peoples in most countries that began as settler colonies are almost universally subject to regimes of extreme injustice where the bias of power is pronounced even when it comes to the supposedly disinterested venue of litigation.

Canada Before and After 1867

When Dan George went to the speaker’s podium to deliver his Centennial Year speech at the Vancouver Coliseum on July 1st of 1967, Canada was in reality far older than 100 years. The celebration was, to be precise, the 100th anniversary of the British North America Act, legislation enacted by the British Parliament. The founders of the first Canada were the makers of the French-Aboriginal fur trade, the main economic and geopolitical dynamo of New France. Throughout the 1600s and early 1700s the Iroquoian term, “Canada,” gradually became the informal name of New France, a vast but ill-defined geographic expanse whose ownership and control was firmly in the hands of Aboriginal peoples except for a narrow strip of French-speaking Roman Catholic settlements along the north shore of the St. Lawrence River.

The fur trade with the Aboriginal peoples of Canada survived the fall of New France in 1759. Responding to the military assertions of Pontiac and the Indian Confederacy, the authors of the Royal Proclamation of 1763 refashioned the old French claims in the region of the Great Lakes area and the Mississippi Valley as “lands reserved to the Indians as their hunting grounds.” The Royal Proclamation established the constitutional foundation of British imperial Canada, a polity that continued and expanded the fur trade through the activities of the Montreal-based Northwest Company. The term, “fur trade,” is a deceptively simple phrase identifying an elaborate complex of cultural, commercial, political, diplomatic, familial, and military connections that came to dominate the geopolitical governance of British imperial Canada until the early decades of the nineteenth century.

As James McGill, one of Montreal’s most influential fur trade entrepreneurs argued in the War of 1812, “The Indians are the only allies who can aught avail in the defense of Canada. They have the same interests as us, and alike are objects of American subjugation, if not extermination.” Similar sentiments were expressed by representatives of the Montreal and Quebec City chambers of commerce in a letter to the British Colonial Office in 1812. These businessmen equated the “protection of Indian Rights and the Security of the Canadas,” a phrase that helps to explain the depth of historical meaning behind the reference to Aboriginal and treaty rights in section 35 of the Constitution Act, 1982.

With close attention to the hostility of the US government towards the alliance linking the British Empire with North American Indians through the vehicle of the fur trade, the Canadian correspondents tried to convince their British governors as follows: “[The Indians] are the true proprietors of the territory [north of the Ohio River]. Their [Aboriginal] rights having never been acquired by us, could not be transferred to others without manifest injustice.” This comment refers to the decision of the British government to deliver lands north of the Ohio River to the possession of the US government in the Treaty of Paris of 1783 even though this vast domain south of the Great Lakes was recognized by the British sovereign as protected Indian territory in the Crown-Aboriginal Treaty of Fort Stanwix of 1768. Negotiated on the Crown side by the Red Tory patriot, Sir William Johnson, the Treaty of Fort Stanwix was the first agreement made with the Aboriginal peoples of Canada according to the terms of the Royal Proclamation of 1763. The Indian provisions in the Royal Proclamation of 1763 largely embody the advice flowing to the London from the busy pen of Sir William Johnson, who included among his many missions the goal of bringing the best innovations from French Indian policy in North America to the service of the British Empire.[11]

The fur traders continue, “This injustice [of the land transfer of 1783] was greatly aggravated by the consideration that those Aboriginal Nations had been our faithful allies during the American Rebellion now called Revolution—and yet no stipulation was made in their favour.” The Canadian correspondents go on to advocate military and diplomatic action to limit the extent of the United States to the region south of the Ohio and Missouri rivers and east of the Rocky Mountains. They justify this course of action by equating the “the protection of Indian Rights and the Security of the Canadas.”

The fur traders’ reference to “the Canadas” came about as a result of the division of what remained of Quebec in 1791 into Upper Canada and Lower Canada. Upper Canada was created on the advice of Sir William Johnson’s son primarily for those English-speaking and Protestant so-called United Empire Loyalist who fled the new republic but who did not want to live within a province where the Roman Catholic religion, the French language, and seigneurial land tenure system prevailed. Then in 1840 in response to an armed uprising of disaffected French Canadians, the British imperial government created the United Province of Canada with the aim of curtailing the power of the descendants of the original canadiens. The British North American Act of 1867 divided the United Province of Canada into its older constituent parts, renaming an expanded Upper Canada as Ontario and Lower Canada as Quebec. The BNA Act confederated Ontario and Quebec with Nova Scotia and New Brunswick, preparing the constitutional machinery for the subsequent addition of the fur trade domain of the Hudson’s Bay Company, the settler colony of British Columbia, the island colony of Prince Edward Island, the arctic islands, and, in 1948, Newfoundland, all within the coast to coast to coast framework of the Dominion of Canada.

In 1867 the British imperial government made Ottawa the capital of the Dominion of Canada. Near one of the highest banks on the mighty Ottawa River, just a stone’s throw from Victoria Island, the Parliament of Canada was raised high into the radiant Canadian sky. Among the jurisdictional responsibilities assigned to the Canadian Parliament by the BNA Act’s makers were coastal and inland fisheries. Section 91(24) of the BNA Act also apportioned “Indians and lands reserved to the Indians” to the jurisdiction of the Dominion Parliament in Ottawa. A constitutional dispute over the legal meaning of the words, “lands reserved to the Indians,” took place in the late 1880s before the highest court in the British Empire.

In the St. Catherine’s Milling case the government of Ontario defeated the national government of John A. Macdonald thereby weakening the positions of both the Aboriginal peoples and Dominion authority in Canadian federalism.[12] This weakening of both is very much on display in the case of Kwitsel Tatel where it is a provincially-appointed jurist passing judgment on a matter that puts front and centre the federal government’s concurrent jurisdiction over fish, Indians, and the federal authority’s responsibility to act as the trustee of the Aboriginal estate in Canada. This federal function is referred to as the Crown’s fiduciary responsibility, a federal duty of protection that the Dominion government has generally ignored without serious legal consequences.

One of the constitutional pointers to the federal government’s responsibilities as the trustee of the Aboriginal estate in Canada isa reference in section 109 of the BNA Act. This section refers to the provincial claims to ownership and control of natural resources within provincial boundaries as being “subject to any Trusts existing in respect thereof, and to any Interest other than that of the Province in the same.” Clearly the Crown obligations and commitments to the Aboriginal peoples of Canada flowing from the Royal Proclamation of 1763 and the 90 or so Crown-Aboriginal treaties are classic examples of such trusts. Another form of trust arises because of the infantilization of registered Indians in the Indian Act. By legally categorizing adult Indians as legal children of the federal father, Canada’s Indian wards were stripped of the ability to represent themselves in various kinds of votes, negotiations, and contractual transactions. By pushing registered Indians outside the representational structures of the federal franchise and the agencies of Canadian federalism, the federal trustee of its Indian wards acquired a legal responsibility to safeguard the rights and serve the best interests of those stripped of their rights to represent themselves.

The Indian Act as a Violation of Human Rights as well as of Existing Aboriginal and Treaty Rights

The Canadian Indian Act originated as one of the world’s most classic expressions of colonial philosophy during the era when imperial rule was made to seem to those on the dominant side of the relationship as a natural expression of the imagined superiority of some over the imagined inferiority of others. Beginning in the era of its founding, the Parliament of Canada passed into law a series of Indian Acts detailing rules for the Ministry of Indian Affairs’ governance of registered Indians on Indian reserves. In conceiving of this relationship and implementing it, it is almost as if Canadian politicians drew on the country’s heritage as a colony of France and then of Great Britain to replicate the patterns of empire in the internal colonization of northern North America’s Indigenous peoples.

In replicating on a societal scale the relationship between parents and children, registered Indians were not allowed to vote in federal elections until the 1960s, just a few years before Dan George delivered his Centennial address. Although the disenfranchised wards of federal authority were prohibited from voting or running in nationwide elections, the outcome of these federal votes determined, among a broad array of matters, how Indian people, Indian lands, Indian waters, and Indian reserves would be governed. The undemocratic character of this regime of internal colonialism has never been overcome. Registered Indians still live out their lives in a system of governance not of their own making that is enforced without their consent. The Indian Act thus violates in a massive and elaborate way the existing Aboriginal and treaty rights that are recognized and affirmed in section 35 of Canada’s Constitution Act, 1982. The obvious legislative instrument to replace the unconstitutional Indian Act would be a Section 35 Implementation and Enforcement Act whose terms would be negotiated along the lines of a treaty of national reconciliation requiring consent from all effected parties.

To gain a proper understanding of the genesis and true character of the Indian Act it is important to go back to the enactment of the first Indian Act which became law in the United Province of Canada a decade before the creation of the Dominion of Canada in 1867.[13] The Dominion government would draw on this earlier Indian Act as it sought to implement the power delegated to it by section 91(24) of the BNA Act of 1867. The first Indian Act came about as part of a cost-cutting process beginning in the late 1840s that saw the British imperial government delegate powers to local governments in those parts of the British Empire dominated by European immigrants and their descendants. This transfer of power over many areas of jurisdiction was part of a decentralization and downloading of authority generally described in Canada as “responsible government.”

In 1857 the local legislature of the United Province of Canada acted against the clearly articulated wishes of many Indian people who by then resided on Indian reserves scattered throughout the former Upper and Lower Canadas. Local non-Indian politicians, many of them land speculators working closely with railway companies, happily agreed to take over from the imperial government responsibility to govern Indian people who lacked any formal representation whatsoever in the Legislature of the United Province of Canada.

This transfer of power over Indians from the imperial government to the jurisdiction of local legislatures dominated by land speculators violated the main essence of many solemn promises made by British imperial authorities to Aboriginal peoples in the course of their efforts to try to persuade Indians not to oppose British colonization. The quid pro quo on the Aboriginal side was that the Aboriginal peoples of Canada would enjoy in perpetuity the benevolent protection of the imperial Crown from the incursions of wave after wave of non-Aboriginal settlement. The imperial government’s transfer of powers to the local legislature of the United Province of Canada was replicated in the delegation of powers to the newly-created Legislature of British Columbia and of the other British colonies in North America. These transfers directly violated the main recommendation of the report of the Select Committee on Aborigines in British Settlement. It presented its recommendations to the Westminster Parliament in Great Britain in 1837.

Of the work of this committee South African historian, Noel Monsert, has written, “The Aborigines Committee remains one of the most striking and impressive examples of public inquiry in nineteenth century Britain.” Monsert describes the Committee’s “massive report” as “one of the most absorbing public reports of the century”.[14]

The British parliamentarians who studied the effect of British colonization of Indigenous peoples throughout the so-called White colonies of the British Empire advised against handing over power to those with much to gain from taking over Aboriginal lands and resources. So often, the British parliamentarians observed, “the representative body is virtually a party” to “disputes with native tribes.” Because of the direct gains available to local land speculators from the dispossession of Indigenous peoples, the local assemblies “ought not to be the judge of such controversies.” The potential for conflict of interest was too great. Rather, “the protection of the aborigines should be considered a duty particularly belonging and appropriate to the Executive Government, as administered either in this country or by the Governors of the respective colonies.” By following such advice the British government could avoid “the guilt of conniving at oppression.”[15]

The first Indian Act was entitled as An Act for the Gradual Civilization of the Indian Tribes in Canada. The bill created a legislative vehicle for the imagined transition of individual Indians in Canada from savagery to civilization. As part of the legislation a procedure was created for adult Indian males to apply for status as enfranchised Canadian citizens who could vote in Canadian elections. In those days the franchise adhered exclusively to those adult males who owned land, an impossibility for registered Indians whose reserves were held, and continue to be held in trust by the federal Crown. Thus a key to moving a man from registered Indian status to the status of a Canadian citizen was the cutting off of a piece of a collectively-held Indian reserve for him to be held as private property.

In this fashion the legal impediments were to be removed for the assimilation of the newly-minted citizen into the Canadian body politic. The makers of the first Indian Act imagined that the Indian reserves would thereby be gradually diminished through fragmentation into bits and pieces of private property to be bought and sold in the prevalent market system. Indians would thus over time cease to exist as a distinct legal group and Indian reserves would be institutionally assimilated into the surrounding mix of municipalities and accompanying agencies of taxation and local self-governance.

There is a direct line of continuity pointing from the first Indian Act to provisions in Bill C-45 that adopt the assimilationist imperatives advanced by Professor Flanagan in his book, First Nations? Second Thoughts.[16] Like the Act for the Gradual Civilization of the Indian Tribes in Canada, provisions of Bill C-45 would advance the privatization and municipalization of Canadian Indian reserves in direct contravention to the Canadian constitution’s recognition and affirmation of existing Aboriginal and treaty rights.

In the mid-nineteenth century as in the time of my writing of this text during the rise of the Idle No More movement, Aboriginal peoples have made it clear that the downgrading of Aboriginal Affairs to lower and lower orders of non-Aboriginal governance is unacceptable to them. The Aboriginal peoples of Canada have made a concerted point of declaring that these initiatives have been pushed forward without their consent. In 1858 many Indian delegations from both the Anishinabek and Iroquoian communities in Canada gathered on the Six Nations Territory in the Grand River Valley to formalize their opposition to the local government’s Indian Act initiative.

Six Nations spokesperson, John Smoke Johnson, attempted to speak for the assembled leaders by stating, “They do not wish to be given over from the care of the Imperial Government to the care of the provincial one.” Spokespeople for Idle No More expressed similar opposition to efforts by the Harper government to abandon federal responsibilities for Indian Affairs and fisheries in order to advance the further enrichment of land speculators and resource extraction companies that by and large derive their charters of possession and exploitation from provincial legislatures.

One delegate asserted at the 1858 assembly in the Grand River Valley that the first Indian Act “blasts our dearest hopes as a race.” Another declared, “There is nothing in [the legislation] to be to our own benefit; only to break us to pieces.” In the minutes taken during the assembly of 1858 there are repeated references to how the downgrading of Crown relations with the First Nations made the wampum belts signifying old treaty agreements with the imperial sovereign appear black. This invocation of blackness signified that the long heritage of Crown promises to the Aboriginal peoples of Canada was being broken and violated.[17]

The Aboriginal hostility to the province of Canada’s Act for the Gradual Civilization of the Indian Tribes set in motion a bureaucratic response that made officials in the Indian Department of the Canadian government increasingly authoritarian. Because registered Indians lacked the franchise there were few political consequences arising from systematic attacks on the human rights, democratic rights, and civil rights of registered Indians. Because there were so few constraints on the power of those civil servants who built solid careers in the Indian Department’s bureaucracy, the Indian Act was expanded to cover more and more facets of Indian life. Between 1927 and 1951 this propensity for authoritarianism extended to a draconian provision in the Indian Act outlawing Indian money transfers to lawyers and to other agents of change to achieve shared objectives in court and Parliament. This approach verged on picturing the effort of Indian people to survive as Indians as sufficient evidence for criminal investigations and prosecutions.

Kwitsel Tatel’s maternal grandfather, Henry Pennier, sought to remove himself from the tyranny of the Indian Act when as a young adult he opted to become an enfranchised Canadian citizen by having himself removed from the federal registry of status Indians. With his enfranchisement came a grant of free hold tenure to a tract of land removed from the collectively-held Indian reserve of the Chehalis band on the Fraser River. When Henry Pennier moved from being a registered Indian to an being an enfranchised Canadian citizen, Kwitsel Tatel’s maternal grandmother, Margaret Leon, technically she lost her Indian status too. This detail, however, did not stop Crown authorities from charging her, convicting her, and jailing her for violating the Indian Act’s prohibition on Aboriginal singing and dancing. The farce continued when Crown officials stripped Henry Pennier of the land alienated from the Chehalis reserve at the first possible moment for non-payment of taxes. Such stories are all too common in the course of an intergenerational assault to eliminate many Aboriginal impediments to the creation of the settler state of Canada in its present form.[18]

The Indian Act tradition that began in 1857 and continues to this day in Canada embodies an ongoing assault on the tradition of voluntary and reciprocal relationships informing the Royal Proclamation of 1763 as well as the various series of Crown-Aboriginal treaties that flow from it. The so-called Maritime treaties covering the east coast of Canada emerge from an earlier phase of English colonization along North America’s Atlantic coast. The Indian Act’s drawing of a clear legal distinction between Canadian citizens and registered Indians, natural persons and non-persons, was an expedient of territorial appropriation and expansion that was replicated in the United States.

The transformation of Indigenous peoples in North America into wards of the federal governments removed from those so categorized the possibility of taking to court corporate entities and private individuals who enrich themselves by acquiring new capital on the imploding frontiers of Indian Country. Prominent among these corporate entities were the railway companies whose primal capital was the Aboriginal land taken from Indian people and reapportioned to the barons of inland transport by political cronies in Washington and Ottawa.

A dubious form of symmetry accompanied these transactions. By defining Indian or tribal status outside the framework of rights and responsibilities attached to citizenship, most Indigenous peoples were stripped of their legal status as “natural persons,” a term that can be equated with the concept of citizenship. At the same time the railway companies and other corporate entities engaged in displacing the Indian wards of federal authority gained the status of legal persons for the purpose of suing, being sued, or making contracts.[19] The anomaly of conferring the rights of personhood on corporations while the Indigenous peoples of North America were legally reconstituted as non-persons occurred over the course of a century that saw the transformation of much of North America into a domain where the lion’s share of living space and natural resources was reserved for non-Aboriginal ownership and exploitation.

This inequity was maintained, to the vast advantage of some and the enormous disadvantage of others, until the era when Dan George addressed his audience of 35,000 people in the Vancouver Coliseum. Not surprisingly the opening of the legal floodgates to civil litigation on Aboriginal rights and Aboriginal title tended to gain momentum especially in the unceded, unsold, and unconquered territories comprising most of British Columbia. With backing from the Anglican Church of Canada, lawyer and later Judge Tom Berger worked closely with Frank Calder and other Nisga’a leaders in British Columbia to resuscitate the constitutional heritage of the Royal Proclamation of 1763 that had remained essentially dormant since the adhesion to Treaty 9 in 1929. Judge Tom Berger was a protégé of lawyer Tom Hurley, the legendary fighting Irishman who often represented registered Indians during the era when they could be criminalized even as they were prevented from defending their rights and titles in court.[20] As Kwitsel Tatel clearly recalls, both Hurley and Berger represented her mother, Rene, in a number of successful defenses against Crown charges of fishing violations.

The Thunderbird Takes Flight

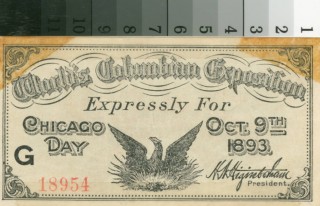

Dan George’s speech can be pictured as part of a larger genre of Aboriginal commentary that tends to find expression every time anniversaries of various acts of colonization are valorized through commemorative celebrations. One such celebration was delivered in 1893 at the World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago Illinois. The Chicago world’s fair was conceived and built to commemorate the 400th anniversary of the so-called “discovery” of the Americas by Christopher Columbus.[21] By setting the location in what was then the frontier metropolis of Chicago, the US government was advertising a conception of itself as the inheritor of Columbus’ role in leading the western expansion of so-called Western civilization.

One of those who called into question the ideals of the World’s Columbian Exposition of 1893 was Simon Pokagon, an Aboriginal intellectual of the Potawatomi nation whose ancestral territories include the Chicago area. Pokagon had complained that the opening ceremonies lacked any Aboriginal viewpoints. He persuasively expressed this opinion to the Exposition’s organizers. Pokagon made the case that the chosen speakers in the opening ceremonies of the Columbian Exposition had articulated only one perspective on the transformative events of 1492. For instance railway promoter Chauncey Depew described Columbus as a kind of all-purpose saint of imperial expansion. Of Columbus Depew remarked, “Neither marble nor brass can fitly form his statue. Continents are his monuments and unnumbered millions, past, present, and future to come, who enjoy in their liberty and their happiness the fruits of their faith, will reverently guard and preserve from century to century his name and fame.”

Kentucky’s Henry Watterson echoed Depew’s sentiments, asserting from the podium, “We meet this day to honour the memory of Christopher Columbus, to celebrate the four-hundredth annual return of the transcendent achievement, and, with fitting rites, to dedicate to America and the universe a concrete exposition of the world’s progress between 1492 and 1892. No twenty centuries can be compared with this in its wide significance and reach; because since the advent of the Son of God, no event has had so great an impact upon human affairs as the discovery of the Western Hemisphere.”

Pokagon responded to the World Columbian Exposition’s hagiography of Christopher Columbus when he was invited to the podium on Chicago Day, one of many specially-designated days that took place over the course of the big event. Pokagon described the trans-Atlantic voyage of Christopher Columbus as the inception of a kind of ongoing funeral, reminding the audiences that the abundant successes on display in the Chicago world’s fair had been achieved “at the sacrifice of our homes and a once-happy race.” He ended his speech by observing, “And so we stand upon a seashore, chained hand and foot, while the incoming tide of the great ocean of civilization rises slowly but surely to overwhelm us.”[22]

Dan George offered a similar counterpoint to the flood of celebratory messages accompanying the one-hundredth anniversary of the creation of the Dominion of Canada in 1867. George asked rhetorically, “How can I celebrate with you this Centennial Year—this hundred years. Shall I thank you for the reserves that are left me of my beautiful forests? Shall I thank you for the canned fish of my river? Shall I thank you for the loss of pride and authority—even amongst my own people?”

The voice of Dan George was a lonely one providing a counterpoint to the glowing assertions of national pride in an event that captured the imagination and goodwill of many Canadians. The popular effusions of optimism about the potential of Canada for national greatness in 1967 contrast eerily with the prevalent imagery of Canada in 2012 as a place of austerity rather than abundance, as a place whose national government is devoted more to the culture of war than the arts and sciences of peace keeping. Some of the greatest expressions of enthusiasm came in response to Expo 67, the hugely successful World’s Fair that took place on an island in Montreal. Without a doubt Expo 67 became the centerpiece of Canada’s Centennial Year. The ideas and hopes that Expo 67 helped to generate transformed the political culture of Canada for years to come. The spotlight on the cultural and political dynamism of Expo 67’s host city, for instance, helped prepare the ground for the rapid rise to prominence of the flamboyant Montreal lawyer, professor, journalist, trade unionist, and politician, Pierre Elliot Trudeau.

In the national election of 1968 Trudeau and his Liberal Party colleagues were voted into power as the national government of Canada. One of Trudeau’s first major initiatives in power was his government’s White Paper seeking to bring treaties to an end through a massive initiative in forced assimilation to transform registered Indians into undifferentiated Canadian citizens without distinct status. In the White paper it seems Trudeau was applying to registered Indians the philosophy he most dearly wanted to apply in resistance to the claims and assertions of his main political enemies. These enemies in the formed an independence movement who wanted to build up the sovereign authorities in international law of Quebec and the Québécois.

Trudeau later withdrew the White Paper in response to its rejection by Indian leaders including Harold Cardinal. Cardinal’s 1969 text, Unjust Society, announced a new assertiveness in insisting that Crown-Aboriginal treaties transacted in the British colonization of Canada must be respected for as long as the grass grows, the sun shines, and the water flows.[23]

The Canadian Indian pavilion was one of many hundreds of national, corporate, and cultural exhibitions that Made Expo 67 such a substantial success. Montreal’s World’s Fair of 1967 commanded attention that in its own way was comparable to that generated by the legendary Columbian Exposition mounted in Chicago in 1893. Built predictably in the shape of a giant teepee, the Canadian Indian pavilion was at every stage of its planning, development, and operation the site of hot contention between the Ministry of Indian Affairs and the Indian advisory committee that gave advice to the federal government on the showcase’s content. The full drama of this contentiousness remains hidden from full view because the records in the National Archives of Canada on this episode of acrimony remain closed to the public. While the details of what transpired have been put under lock and key, however, it is clear that the Aboriginal advisers on the project tried not to bend to the dictates of Canadian government officials who maintained final say on what was or was not to be displayed in the pavilion. The disputes over what would or what not be shown in the Canadian Indian Pavilion at Expo 67 anticipated the nature of many disputes to come such as when the National Indian Brotherhood of Canada responded to the assimilationist approach of the White Paper with a document that was meaningfully entitled, Indian Control of Indian Education.

When Dan George gave his speech in 1967, he did so in an urban centre that still resided in the shadow of Montreal, the city on an island in the St. Lawrence that since its inception in the 1600s was the main metropolis of Canada. Dan George concluded his oratory with an electrifying ode to education as the most promising gateway away from the darkness of isolation to the brightness of a more outward-looking Aboriginal role in Canada and the world. George concluded,

Oh God—like the Thunderbird of old—we shall rise again out of the sea—we shall grasp the instruments of the white man’s success—his education—his skill—and with these new tools I shall spirit my race to the proudest segment of your society… I shall see our young braves and our chiefs sitting in the house of Law and Government—ruling and being ruled by the knowledge and freedom of our great land. So shall I shatter the barriers of our isolation. So shall the next hundred years be the greatest in the proud history of our tribes and nations.

Dan George’s prediction is arguably coming true in the growing importance of post-secondary education in the political economy of Aboriginal life in Canada. This change is reflected in the increased numbers of Aboriginal post-secondary students from a mere handful in 1967 to over 30,000 in 2013. In 1989 Prime Minister Brian Mulroney’s Minister of Indian Affairs and Northern Development, Pierre Cadieux, dramatically opened the question of whether or not federal funding for Aboriginal post-secondary education is a treaty right.

In announcing a cap to the apportionment by his ministry of funding for Aboriginal post-secondary students, Cadieux declared, “Since the actual words in the treaties do not refer to higher forms of education, I simply cannot base a post-secondary program on treaty rights. Additionally not all Indians are protected by treaties and not all treaties mention education.”[24] These comments were widely perceived in Indian Country as a kind of declaration of war on many Indian people who shared Dan George’s view of higher education as the primary venue of escape to a safer, more viable, and more esteemed place in Canada and the world.

In hunger strikes, demonstrations across the country, and Aboriginal caravans descending on Ottawa, many Aboriginal students and their families mobilized to insist that federal funding of Indian post-secondary education was indeed a Crown response to the terms of many treaty agreement with First Nations whose binding character was recognized and affirmed in section 35 of the Constitution Act, 1982. The mobilization of students, their immediate and extended families, as well as well their allies of diverse backgrounds, can be seen as an Aboriginal version of the Maple Spring—Le printemps érable—that in 2012 would put a major spotlight of public subsidies to post-secondary education in Quebec.

This well organized Aboriginal response to the capping of federal funding for Indian post-secondary education proved to help set the stage for the massive Aboriginal support for Manitoba MLA Elijah Harper when he emerged as the primary agent in preventing in 1990 the Meech Lake accord from becoming entrenched in the Canadian constitution. The Meech Lake accord would, if it had been passed through the Parliament and all ten provincial legislatures in Canada, have entrenched in the constitution of Canada a provision defining the “fundamental characteristic of Canada.” This definition excluded altogether any reference to the Aboriginal peoples of Canada.[25]

Dumbfounded by the scope and depth of the opposition his comments had stirred up, Cadieux backed away from his original statement. In September of 1989 the Minister of Indian Affairs announced, “I am very much aware of the profound conviction of Indian people that post-secondary education is a treaty right.”[26] His words, however, were not backed up with actions. Cadieux made no commitment to withdraw the cap on federal funding for this purpose. To this day qualified Aboriginal students are denied subsidies for post-secondary education because of limits on federal funding.

The controversy raised many questions that have yet to be resolved. Should the Aboriginal and treaty rights referred to in section 35 be implemented and enforced in ways that apply some across-the-board principles or should Crown-Aboriginal relations be subject to the particular idiosyncrasies of every Crown-Aboriginal agreement? Should there be some sort of combination of minimum standards with the many variations in Crown-Aboriginal relations in different parts of the country? Many other questions come to mind. If, for instance, the cap on funding for Aboriginal post-secondary education did indeed violate section 35, what should be done about it now? In its ruling on the Sparrow case in 1990 the Supreme Court of Canada suggested an answer to this query. Canada’s top judges counseled, “Federal power must be reconciled with federal duty and the best way to achieve that reconciliation is to demand the justification of any government regulation that infringes upon or denies Aborginal [and treaty] rights.”

This single sentence in the Sparrow ruling forms one of the keys to the arguments advanced by Kwitsel Tatel in the second and constitutional phase of her trial. In making her case Kwitsel Tatel has come up with a list that she alleges constitute 35 infringements of section 35. The defendant in trial number 47476-1 has derived many of the items in this list by characterizing her own treatment by Crown officials in the course of their criminalizing her for possessing fish.

Should some sort of justification be sought for the federal capping of funds directed towards the sponsorship of Aboriginal post-secondary students? Should possible infringements of section 35 be arbitrated by employing an issue by issue, case by case, community by community methodology similar to that outlined in the Supreme Court’s Van der Peet ruling which lays out very onerous criteria for proving the existence of Aboriginal and treaty rights? How many hundreds, thousands, or tens of thousands of infringements of Aboriginal and treaty rights have taken place in the process of creating the settler state of Canada? Who is responsible for answering the demand for justifications of the real or imagined infringements of section 35? Should there be some frameworks and procedures set in place so that the “best way” for “reconciling federal power with the federal duty” can be more readily applied. Surely the best way to prevent unjustified infringements of section 35 is to implement and enforce Aboriginal and treaty rights, an obligation that the federal government of Canada has notoriously neglected.

Aboriginal and Treaty Rights in Domestic

and International Law

One of the main dilemmas faced by the Aboriginal peoples of Canada is the systemic cycles of entrapment they face as they struggle within the domestic limitations of the Canadian state as presently constituted. In so many instances, as in the positions consistently advanced in court by the so-called Ministry of Justice, Canada’s treatment of Indigenous peoples cannot stand up to outside scrutiny. Even when government maltreatment of Aboriginal peoples is clearly identified outside Canada, however, the conventions of non-intervention shared by sovereign nation states prevent the international community from acting assertively and in concert to protect the human rights of Indians, Inuit and Metis in Canada.

A small but significant reversal took place in 1982 when Indian, Inuit and Metis were described in Canada’s supreme law as the Aboriginal peoples of Canada. In many of the laws and conventions of the United Nations the unit, “peoples,” is identified as the primary collectivity to which rights and responsibilities adhere. The UN Charter, for instance, begins by invoking the authority of “We the Peoples of the United Nations.” Similarly, the constitutional recognition and affirmation of “treaty rights” in section 35 invokes the term that is most synonymous with international law. Only collectivities with the inherent right of self-determination are in a position to enter into treaties. Put another way, no entity could enter into treaty relations with another entity based entirely on delegated authority. Treaty talk is the very quintessence of the language of sovereignty

The international implications of the juridical innovations invoked by section 35 may turn out to be one of the most consequential and redeeming experiments in law ever attempted in Canadian history. Clearly Canada’s invocation of Aboriginal and treaty rights has implications that cut far beyond its own borders in a world where the colonization of Indigenous peoples has proven to be so ubiquitous and so influential in defining relationships of power right up to the present day. But the international dimensions of Canada’s recognition of the Aboriginal and treaty rights of the Aboriginal peoples of Canada will be difficult to address in the global community as long as the government of Canada, including the Ministry of Justice and the Supreme Court, maintains a unilateral dominance over the exercise, implementation, arbitration, and enforcement of the rights, titles, treaties, and other relationships invoked by section 35 of the Constitution Act, 1982.

The tight domestication of Aboriginal and treaty rights is especially constraining in countries such as Canada, the United States, New Zealand, and Australia. In these polities and others like them, those most subject to the oppressions of internal colonialism form small and marginalized minorities. The prevalent system of majoritarian decision making in such environments is severely stacked against any reversal of the regimes of Aboriginal dispossession and disentitlement that have developed enormous momentum over the years. This propensity is especially true in hot spots of farming and real estate transaction such as the Fraser Valley of British Columbia, a zone with a relatively high Aboriginal population that is being rapidly integrated into the urban metropolis of Greater Vancouver.

Awareness of the strength of the domesticating entrapment attending the accelerating pace of Aboriginal dispossession in Canada is integral to the most pessimistic assessments of the Aboriginal condition offered by both Dan George in 1967 and more recently by his adopted granddaughter, Kwitsel Tatel. Their calculations of how much has been lost, and is being lost, to the Aboriginal peoples occurs in a country whose political economy is tied for the foreseeable future to large-scale immigration.

As surely as both the prevention of piracy or the bringing of an end to slavery required international cooperation through international interventions, the ongoing dispossession and disentitlement of Indigenous peoples require the involvement of appropriate agencies that draw their mandates from international as well as national bodies. There are old and well-entrenched blockages of national sovereignty that mitigate against the achievement of true third-party adjudication of Aboriginal and treaty rights in international arenas of jurisprudence. Until such international venues of binding arbitration become accessible to Indigenous peoples in many countries, however, national governments including Canada’s will continue to play fast and loose with their own laws. They will do so in concert with the object of making sure that the Aboriginal and treaty rights, like the peoples in whom they are invested, stay on the sidelines of national development so as not to engender any major disruptions to the inherent inequity of the distribution of wealth and political power in settler states.

The government of the United States of America has led the way in efforts to fend off any intervention by other countries in the imperial republic’s displacement, removal, and elimination of Indigenous peoples in the course of its transcontinental expansion. Lewis Cass was the official put in charge of domesticating so-called Indian Affairs in the United States after the Napoleonic wars that in North America gave rise to the War of 1812.[27] Over the course of his career Cass was a fur trader, a Governor of Michigan Territory, a US Ambassador to France, as well as a US Secretary of State. Cass’s specific assignment in the domestication of Indian Affairs was to persuade public opinion in Great Britain that the United States would treat Indigenous peoples benevolently in the course of its future westward expansion.

Cass’s main objective was to hasten the disengagement of the British government from any formal relationship whatsoever with the Indigenous peoples on the moving frontiers of the United States. Cass advanced this agenda through his authorship of articles in the pages of the North American Review, a publication that claimed a large readership in Great Britain. In the late 1820s and early 1830s Cass advanced his arguments by criticizing the writings of John Dunn Hunter, an Indianized White Man with an influential audience in Great Britain that included the well-known industrialist, Robert Owen.[28] Cass’s preoccupation with domesticating so-called Indian Affairs in the United States led him to counter the contentions of those in Great Britain who emerged from the War of 1812 believing “our cause was common with that of the Indian nations. Against them as against us [the British], the Americans have been the real aggressors.”

In the end Cass resorted to an appeal to the shared heritage of Great Britain and the United States in his effort to persuade the people and the imperial government of the United Kingdom not to intervene where the business of the US War Department converged with the business of the US Bureau of Indian Affairs. Cass described the United States as “the great depository of English literature and science and arts, and the living evidence of English intelligence and principles.” This conciliatory approach, however, came only after Cass had attacked the alleged hypocrisy of the British criticisms of US Indian policy. In Cass’s arguments, British abuses of Indigenous peoples in the Crown’s imperial colonies and in the fur-trade domain of the London-based Hudson’s Bay Company were said to far exceed US maltreatment of Aboriginal peoples.

Cass was especially critical of the British alliance in the War of 1812 with the Indian Confederacy led by the martyred Shawnee sage, Tecumseh. Tecumseh’s ability to inspire the mobilization of about 12,000 Aboriginal warriors against the United States, but especially in the downfall of the US post at Detroit, saved Canada during its most menaced hours. The Indian Confederacy prevented what remained of Canada from falling under the sovereign authority of the Stars and Stripes. The Indian Confederacy’s opposition to US expansionism during the War of 1812 amounts to the most concerted and well-organized Aboriginal resistance ever mounted to the transcontinental movement of the United States.[29]

Not surprisingly, however, Lewis Cass swept aside these historical facts to misrepresent the motivations and trans-tribal unity of the pan-Indian Confederacy as the work “of deserters from a few tribes.” Of Tecumseh’s Indian Confederacy Cass wrote, “The acknowledged government of each tribe disavowed any participation in their projects. And they were in fact a lawless predatory band, observing no common authority, and seeking no national object.”[30] In presenting this assessment Cass anticipated many similar government efforts to discredit those groups, including the American Indian Movement and the AIM-related Mohawk Warriors, whose actions in the self-defense of Indian Country really have affected the course of history.

The US effort to treat Indian policy as an area of exclusive domestic concern would be matched in later years by efforts to fend off international interventions into the US role in the slave trade and in the legal infrastructure of slavery especially as it might effect the extremely lucrative cultivation of cotton throughout the southern states of the US republic. After US slavery was at last outlawed in the course of the US Civil War, the US government continued to veer away from any initiative that might lead to outside intervention in what it considered its own exclusive field of domestic jurisdictions. The US government opted, for instance, not to take part in the League of Nations even though it was a US president that proposed the creation of such an international body in the closing phase of the First World War.

This hostility to the very concept, let alone the implementation and enforcement of international law, remains to this day a major attribute of the ailing superpower’s orientation to the outside world. From the era of its transcontinental expansion until the present, the US government prefers to deal with the rest of the world from the base of its control over massive arsenals of weaponry rather than by building up and living within the requirements of treaty law. In the international arena treaty law forms the main element of the rule of law.

The notorious US disregard for living up to its promises in its 400 or so treaties with Native American peoples initiated a trend that is now prevalent globally. On a planet where the imperatives of military muscle and might is right have been made to prevail in so many ways over the rule of law, the prospects diminish that the Canadian government or any other government will opt to live within the juridical constraints of Aboriginal and treaty rights. Until this day, laws are enforced selectively, providing maximum protection for the rich and the powerful and often no protection whatsoever to those who are most vulnerable to the incursions of predators and land grabbers.

The governments of the United States, Canada, New Zealand and Australia demonstrated classically their hostility towards the internationalization of Aboriginal and treaty rights when they voted in the UN General Assembly in 2007 against the ratification of the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. As noted in her own letter to Judge Crabtree, Kwitsel Tatel has applied aspects of the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous peoples to the publication of her personal information in “Crime Stoppers.” She sees this initiative as an example of prohibited propaganda whose aim is to promote negative discrimination.

By voting against the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous peoples in the world’s primary international parliament, the governments of the United States, Canada, New Zealand and Australia helped clarify the shared character of the four naysaying governments as the directing agencies of settler states dedicated to maintaining their own domestic entrapments of Indigenous peoples. On the other hand the decision by the majority of countries in the UN to ratify the UN Declaration demonstrates the continuing urge of the majority of the world’s peoples everywhere to continue to work towards decolonization.

This broadly-felt human urge to decolonization was entrenched in the very inception of the United Nations in the Atlantic Charter signed in 1941 by British Prime Minister Winston Churchill and US president Franklin D. Roosevelt. This very short document included the following provisions from the two leaders engaged in preparing their Armed Forces’ to work cooperatively in defeating Nazi, Italian fascist, and imperial Japanese aggression. The two leaders of Anglo-America agreed,

Second, they desire to see no territorial changes that do not accord with the freely expressed wishes of the peoples concerned;

Third, they respect the right of all peoples to choose the form of government under which they will live; and they wish to see sovereign rights and self-government restored to those who have been forcibly deprived of them;

The Atlantic Charter drew on the long history of efforts to restrain the imperatives of empire building by affirming the importance of human rights in declarations such as those that adorned the most idealistic effusions of the French Revolution. The Atlantic Charter helped prepare the way for the UN Declaration on Universal Human Rights, the UN Conventions prohibiting Genocide and Torture, as well as the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP). The governments of USA, Canada, Australia and New Zealand eventually did quietly ratify the UNDRIP.

The so-called “discovery of the Americas in 1492 as celebrated, for instance, in the World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago in 1893, necessitated a close consideration of legal and ethical issues that challenged some of the most basic assumptions in the Judeo-Christian heritage of Western Civilization. Canada’s constitutional recognition and affirmation of Aboriginal and treaty rights in 1982 represents the outcome of centuries of grappling about what to do about the existence of many thousands of distinct peoples in the Western Hemisphere who were not known to the authors of the Bible or the authors of many of Western Civilization’s most classic texts.

Among those who have contributed to the ideals expressed in section 35 are Brother Bartolome de Las Casas of New Spain, Roger Williams and William Penn, founders of two of the thirteen initial Anglo-American colonies, British Superintendent of Indian Affairs Sir William Johnson, Indian Confederacy leader Tecumseh, the architect of the Indian New Deal John Collier, and Thomas R. Berger, a lawyer whose work with the Indians of BC and whose enlightened guidance of a Royal Commission on the Mackenzie Valley pipeline in Canada’s north helped prepare the ground for the entrenchment of section 35.

Definitely Dan George played an important role of his own in helping to influence public opinion so that many Canadians of diverse background would come to see it as an assertion rather than an undermining of their own interests to recognize and affirm existing Aboriginal and treaty rights. It remains to be seen how the assertions of Kwitsel Tatel, Chief Theresa Spence, and the largely female leadership of Idle No More will affect the political and legal evolution of Canada, North America and the world.

ENDNOTES

[1] See Peter MacFarlane, Brotherhood to Nationhood: George Manuel and the Making of the Modern Indian Movement (Toronto: Between The Lines, 1993); George Manuel and Michael Posluns, The Fourth World: An Indian Reality (Don Mills: Collier-Macmillan Canada, 1974)

[2] See Richard Drinnon, Facing West: The Metaphysics of Indian-Hating and Empire-Building (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1997)

[3] Michael Leonardi, “Idle No More: Canada’s Indigenous Resistance Movement, Counterpunch, Jan 4-6, 2013, at

http://www.counterpunch.org/2013/01/04/idle-no-more/#.UOccXv_84b0.facebook

[4] James Mooney, The Ghost Dance Religion and Wounded Knee (1896; New Tork: Dover Publications, 1973)

[5] Dee Brown, Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee: An Indian History of the American West (New York: Holt, Rinehart, and Winston, 1970)

[6] Lawyers’ Rights Watch, Canada, Arrange Meeting Requested by Chief Spence Lawyers’ Rights Watch Tells PM, 29 December, 2012 at

[7] Marci McDonald, “The Man Behind Stephen Harper,” Walrus, October, 2004 at

http://walrusmagazine.com/articles/the-man-behind-stephen-harper-tom-flanagan/

[8] Paul Tennant, Aboriginal Peoples and Politics: The Indian Land Question in British Columbia, 1849-1989 (Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press, 1990)

[9] Sally Weaver, Making Canadian Indian Policy, 1968-1970 (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1981)

[10] Hall, “Fixing Elections Through Fraud: On the Need for a Royal Commission on Election Practices in Canada,” VT, 5 April, 2012, at

https://www.veteranstodayarchives.com/2012/04/05/fixing-elections-through-fraud/

[11] Fintan O’Toole, White Savage: William Johnson and the Invention of America (New York: Farrar, Straus, and Giroux, 2005)

[12] Hall, “The St. Catherine’s Milling and Lumber Company versus the Queen: Indian Land Rights as a Factor in Federal-Provincial Relations in Nineteenth-Century Canada,” in Aboriginal Resource Use In Canada: Historical and Legal Aspects. Jean Friesen and Kerry Abel eds, (Winnipeg: University of Manitoba Press, 1991), pp. 267-286

[13] See Hall, “Native Limited Identities and Newcomer Metropolitanism in Upper Canada, 1814-1867,” in Old Ontario: Essays in Honour of J.M.S. Careless, David Keane and Colin Read, eds, (Toronto: Dundurn Press, 1990), pp. 148-173