Reckoning with the Law of Aboriginal and Treaty Rights in North America

Reckoning with the Law of Aboriginal and Treaty Rights in North America

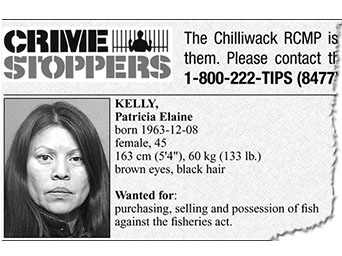

(The Following Text Introduces the Second and Constitutional Phase of the Trial of Kwitsel Tatel [Patricia Elaine Kelly] Now Entering Its Ninth Year. The Trial Began with a Charge Against the Criminalized Coast Salish Fisher for Possessing and Selling Salmon Contrary to the Terms of Canada’s Fisheries Act. The Selling Charge was Dropped by Finn Lensen QC, the Federal Crown Prosector Handling the case. The Narrative Presented Below is Part of a Larger Document Submitted to the Presiding Jurist, The Hon. Thomas Crabtree, the Chief Judge of the Provincial Court of British Columbia Canada. The Trial Resumes of January 14, 2013 in the Law Courts of Chilliwack BC.)

1.1 From Conquest to Aboriginal Consent as a Medium of European Imperial Expansion, 1492-1763

Your Honour, the matters that bring us together in this trial raise to the surface fundamental problems of human rights that first arose with the European christening of our Aboriginal lands and waters as the Americas following Christopher Columbus’s most transformative voyage in 1492. The very name of the jurisdiction where this trial is taking place, British Columbia, invokes the ongoing character of an unbroken saga of imperial expansion.

From my perspective as a citizen of the First Nations, this process of imperial colonization has turned society upside down, subordinating the rights, titles, polities, confederacies, clans, and very persons of the Indigenous peoples to the claims of alien regimes. The priority of these colonial regimes has been to advance the acquisitive aspirations of newcomers, their descendants and their corporate progeny, very often at our direct expense. The Statue of Liberty in New York Harbor was raised as a present from the government of France to celebrate liberty in North America for immigrants, not liberty for the continent’s Aboriginal peoples.

The imperial history of the Americas has seen the Roman Catholic Pope donate in 1493 the realms supposedly discovered by Columbus to the Crown of Castille. The “donation” from the Vicar of Rome was, in part, to honour the role played by the Spanish monarchy in conquering and uprooting the last of the Islamic settlements in the Iberian Peninsula. Until the early decades of the nineteenth century, Spain attempted sporadically to assert jurisdiction over our Aboriginal lands and waters in what is now British Columbia based on the grant of territory as described in the papal bull of 1493, Inter Caetera.

The Spanish claims have been countered by those of Russia and the United States in the imperial history leading up to the assertion of British sovereignty based on earlier claims advanced by the Montreal-based Northwest Company and the London-based Hudson’s Bay Company. The viability of both fur-trade enterprises depended on far-flung networks of commercial, diplomatic, and cultural interaction with the Indigenous peoples of northern North America.

Many major challenges were posed for those on the expansionary side of colonization by questions concerning the human rights and legal status of Indigenous peoples and their Aboriginal lands. In the process of addressing these questions, the law of the so-called community of nations moved closer to what we now refer to as international law. This legal trajectory gained traction, for instance, in 1537, when the Vatican sought to put limits on the dispossession and enslavement of Indians in New Spain by declaring them to be fully human. “By no means,” declared the Pope, should the Indians be “deprived of their liberty or possession of their property, even though they be outside the Christian faith.”

As the protestant powers joined the rush for spoils in the so-called New World, a small but select group of English-speaking jurists gradually developed an important new doctrine. These progressive jurists sought to develop a tradition of constitutional relations with First Nations based on the premise that a primary source of legitimacy for Euro-American settlements originates in the consent of Indigenous peoples for any reconstitution of their Aboriginal land tenure.

This emerging doctrine was marked in the seventeenth century in the negotiations with Indigenous peoples attending the founding of Rhode Island and Pennsylvania. In seeking consent from the Narragansett Indians for the establishment of Rhode Island, Roger Williams introduced the principle that a grant from the English sovereign was not a sufficient basis to render English colonies as fully legitimate. By reaching out to his Delaware Indian neighbours the Quaker leader, William Penn, helped advance the tradition initiated with the founding of Rhode Island. In making a treaty with the Indigenous peoples of the Pennsylvania region, Penn acted on the principle that Aboriginal sanction was needed to invest European colonization with full legitimacy.

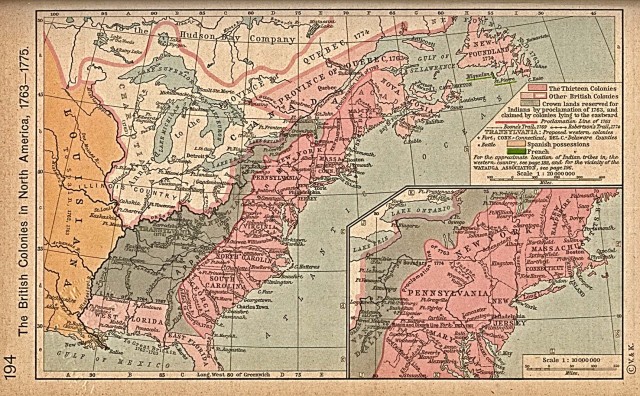

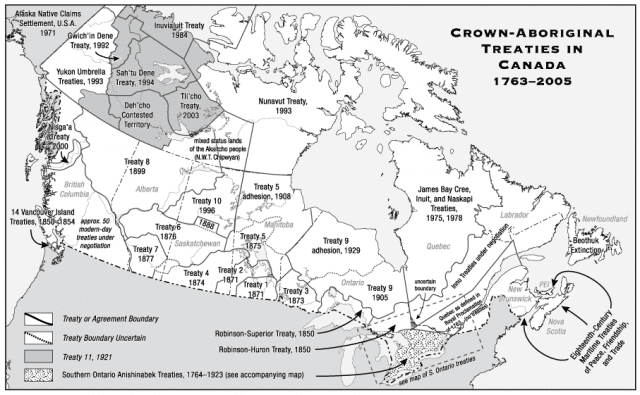

With the help and advice of Sir William Johnson, the imperial government’s first Superintendent of Indian Affairs in the northern half of British North America, the Royal Proclamation of 1763 was formulated. Drawing on the Indian policies initiated by Williams and Penn, the Royal Proclamation included a seminal provision that Aboriginal consent must be obtained before non-Aboriginal settlements could expand. Conquest and unilateral dispossession of Indigenous peoples was thereby prohibited in the westward movement of Anglo-American settlement. This effort to incorporate Indigenous peoples into the British Empire on the basis of voluntarism and the rule of law was deeply resented by many land speculators and pioneer farmers seeking to derive maximum individual and corporate wealth from the unregulated transformation of Indian Country into privatized real estate. [See Anthony J. Hall, A Note on Canadian Treaties,” in Tom Molloy, The World Is Our Witness: The Historic Journey of the Nisga’s into Canada (Calgary: Fifth House, 2000), pp. 3-10; Fintan O’Toole, White Savage: William Johnson and the Invention of America(Albany: State University of New York, 2009)]

1.2 Aboriginal and Treaty Rights or Merciless Indian Savages?

The Royal Proclamation of 1763 or the American Declaration of Independence?

As I see it, Your Honour, the very issues that are in contention in the trial of Kwitsel Tatel were central in the events leading up to the secession of the United States of America from British North America after 1776. The provision in the Canadian constitution that recognizes and affirms the existence of the Aboriginal and treaty rights of the Aboriginal peoples of Canada draws heavily on the legal authority of the Royal Proclamation of 1763.

This Royal Proclamation is referred to specifically in Section 25 of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms. This Royal Proclamation of 1763 lies at the constitutional foundations of Quebec and the rest of British imperial Canada. It created the basis for the government of a dramatically expanded British North America after the government of France withdrew its imperial authority along with its armed forces from New France. Canada was another widely-recognized name for the far-reaching and only-vaguely-defined realm of French claims covering much of Aboriginal North America including much of what is now the United States.

The Royal Proclamation designated much of the newly-annexed territories “as lands reserved to the Indians as their hunting grounds.” It recognized what might be described in today’s terms as Aboriginal title. The Proclamation set up a procedure for the negotiation of Crown-Aboriginal treaties as a necessary prerequisite for the westward expansion of Euro-American settlements. Its provisions essentially outlawed imperial expansion through military conquest and through unrestrained settler vigilantism directed at Indigenous peoples. The Royal Proclamation codified the need to obtain Indian consent before non-Aboriginal expansion into Indian Country could proceed.

The Royal Proclamation was deeply resented by many Anglo-Americans, some of whom expressed their anger at its contents by going on killing sprees directed at eliminating Indian people on the expanding frontiers of Anglo-American settlements. Among the main Aboriginal victims of this particular round of unrestrained vigilantism were a considerable number of Christian pacifists living under the auspices of the Moravian Church.

Many of the critics of the new law of Aboriginal and treaty rights in British North America resented the increased taxes the imperial government attempted to raise in order to pay the salaries of law enforcement officials who would be charged with the responsibility of fending off settler incursions into Indian Country. The job of these law enforcement officials was to block settler invasions of the territory reserved for Indian hunting, fishing, gathering, gardening, mineral extraction, forestry, and communal habitations. This feature of the Royal Proclamation points to the contemporary failures of protection when it comes to the unfulfilled responsibilities of Crown law enforcement officials throughout British Columbia and the rest of Canada. To this very day we still lack in Canada a police force devoted to the task of identifying and protecting our Aboriginal lands, waters, resources, and persons from the hostile incursions of thieves and predators.

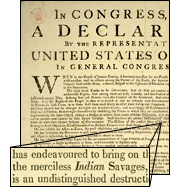

The Anglo-American dislike of the Royal Proclamation helped stimulate a revolt against the British imperial government. The founding of the United States on terms that rejected the rule of law as codified in the Royal Proclamation of 1763 was marked in a striking provision of the American Declaration of Independence issued on July 4, 1776. The founders of the United States proclaimed to the world the existence of their new polity by condemning King George III for many alleged crimes including “bringing on the merciless Indian savages whose known rule of warfare is an undistinguished destruction of all ages, sexes, and conditions.” With these harsh words embedded in its founding manifesto, the United States was born into an ongoing trajectory of frontier conquest and demonology culminating in the many resource grabs from Indigenous peoples throughout the planet that presently go forward in the name of the so-called Global War on Terror and all its many militaristic and anti-democratic spinoffs.

From the perspective of the founders of the United States of America, King George III was considered a tyrant for his embrace in the Royal Proclamation of some of the most basic human rights of Aboriginal peoples. Among the rights recognized by the British Empire’s imperial Sovereign was the Aboriginal right not to be unilaterally dispossessed of our Aboriginal rights and titles to our ancestral lands and waters. In the Royal Proclamation the imperial government made the first of many promises to come that we could not be forced to move aside to make room for incoming settlers without Crown officials first obtaining our formal consent for fundamental reconfigurations of the lands reserved to the Indians as their hunting grounds.

The records of negotiations leading to the formalization of the ninety or so Crown-Aboriginal treaties in Canada flowing in part from the terms of the Royal Proclamation commonly speak of the imperial Sovereign’s obligations to protect our rights, titles and interests for as long as the sun shines, the grass grows and the waters flow. Your Honour, the sun is still shining, the grass will grow again in the spring and the waters continue to flow even though the federal government has recently acted illegally in denying and negating its constitutional responsibilities to protect the environment of fish in approximately 99% of Canada’s aquatic habitat.

Why is it, Your Honour, that there seems to be so much interconnection in the federal government’s failure to live up to its dual responsibilities to protect fish and Indians? Why is it that you, Thomas Crabtree, the Chief Judge of the Provincial Court of British Columbia, have been put in the position of arbiter in these areas of exclusive federal jurisdiction? Why does it fall on you, Your Honour, to determine in the case of Kwitsel Tatel whether the federal government is living up to its dual and intertwined constitutional responsibilities with respect to its trusteeship obligations for the protection of fish and Indians? Who made the decisions that put us in this provincial court and what is the justification for subordinating these two very clear areas of federal jurisdiction to the arbitration of a provincially-appointed judge?

1.3 Aboriginal Title and Crown Title in British Columbia

The basic contentions over Aboriginal and treaty rights that divided the United States from what remained of British North America became integral to the settler politics of British Columbia from the first days of BC’s founding in 1858 until the present. Some in the colonizing society, but especially Anglican missionaries such as Reverends Arthur O’Meara and William Duncan, encouraged us to have confidence that the principles of the Royal Proclamation would eventually be extended to cover the Aboriginal peoples of Canada’s westernmost province.

In the 1870s the Dominion government of Canada applied pressure to the government of British Columbia in a concerted effort to make provincial authorities move towards the legal heritage of the Royal Proclamation by freeing up more land for Indian reserves. This effort began with the Dominion government using its constitutional powers to disallow a consolidation of BC land laws that failed to take the unceded Aboriginal title of the Aboriginal peoples into account. In 1874 the Dominion government’s Minister of the Interior, David Laird, attempted to recognize and affirm Aboriginal and treaty rights by appealing to his counterparts in BC. He implored them to rise to the level of a “great national question,” to resolve the issue of contested titles to the lands and resources of BC “in the spirit of wisdom and patriotism.” [Anthony J. Hall, Earth into Property: Colonization, Decolonization, and Capitalism (Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 20100, pp. 418-420]

In spite of this federal effort and in spite of the many appeals over more than a century by Aboriginal officials to Crown officials in New Westminster, Victoria, Ottawa, and the imperial capital of Great Britain, provincial authorities maintained a concerted unwillingness to bow to the legal imperatives of the Royal Proclamation of 1763. Provincial authorities held to the position that they could apportion private titles and resource-extraction rights to non-Aboriginal individuals and corporations in BC without obtaining Aboriginal consent for the unilateral plundering of our Aboriginal inheritances. As we can see very clearly from the rapid pace of the transformation of the Fraser Valley into non-Aboriginal real estate, this process of dispossession has continued to accelerate over the course of my lifetime.

In spite of this federal effort and in spite of the many appeals over more than a century by Aboriginal officials to Crown officials in New Westminster, Victoria, Ottawa, and the imperial capital of Great Britain, provincial authorities maintained a concerted unwillingness to bow to the legal imperatives of the Royal Proclamation of 1763. Provincial authorities held to the position that they could apportion private titles and resource-extraction rights to non-Aboriginal individuals and corporations in BC without obtaining Aboriginal consent for the unilateral plundering of our Aboriginal inheritances. As we can see very clearly from the rapid pace of the transformation of the Fraser Valley into non-Aboriginal real estate, this process of dispossession has continued to accelerate over the course of my lifetime.

It would not be until the 1990s that a procedure, however fragile, inadequate and tenuous, was adopted for the negotiation of modern-day Crown-Aboriginal treaties in British Columbia. While the negotiation of Crown-Aboriginal treaties in BC began with considerable hope, that optimism has been largely eroded as Crown officials increasingly fall back on old colonial techniques of divide-and-conquer and as they continue to block our access to international instruments of genuine third-party adjudication.

Perhaps the time has come to consider consolidating the treaty process in BC so that there is a single table of Crown-Aboriginal treaty negotiations rather than some sixty or so separate negotiations in a process calculated to balkanize us and disempower us by turning us against one another as has happened, unfortunately, in our shared Sto:lo territory. Perhaps the time has come for First Nations in BC to make a collective decision to withdraw from the treaty process altogether until such time as there is a legitimate national government in place willing to deal with the domestic and international aspects of our unceded title to most of the lands, resources, and waters of Canada’s westernmost province. Perhaps the time has come for us to insist that we negotiate with a single undivided Crown of Canada and treat the course of federal-provincial negotiations on Aboriginal title as the exclusive business of the two non-Aboriginal orders of government. Perhaps it is time to address the reality that our evolving relations with the imperial Sovereign run primarily through the federal government of Canada whose officials, but especially in the so-called Ministry of Justice, bear a major part of the responsibility to protect our Aboriginal rights, titles, resources, governments, interests, and persons from provincial encroachment and from the encroachments of those third parties empowered to occupy our lands and waters without our Aboriginal consent.

Your Honour, perhaps the time has come to break away from the model of Indian reserves as bits of territory on their way to municipal status and to move instead towards a people to people, nation to nation paradigm of negotiations as advocated, for instance, by the Royal Commission on Aboriginal peoples in its “highlights” publication. Perhaps the time has come to make a reckoning with the fact that provincial governments in Canada are not juridically equipped to make genuine treaties whereas this sovereign power does reside in the Crown of Canada and in those First Nations whose presence in northern North America is founded in origins that long pre-exist those of Canada.

No legal rulings on the part of any court can alter the simple reality that our First Nations polities form the first order of governance in the lands and waters of Canada. If there is any question about which form of title counts as a “burden” on another form of title, the answer is to be found in the stark reality that Crown title was imposed on our Aboriginal title, not the other way around. As the imperial history of colonization readily attests, Crown title is a heavy heavy burden on Aboriginal title. Indeed Crown title very often gives rise to the most ruthless means of dispossessing and disinheriting Aboriginal peoples as a class. [RCAP, People to People, Nation to Nation: Highlights of the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples (Ottawa: RCAP, 1996]

1.4 Efforts to Counter the Constitutional Heritage of the Royal Proclamation of 1763 Through Genocide, Cultural Assimilation, and Institutional Assimilation

As I have learned from books, from my parents and grandparents as well as from my own experience, there has consistently been a segment of BC’s settler society that, from its inception, has treated us essentially as those merciless Indian savages referred to in the American Declaration of Independence. The cultural roots of BC’s settler population go back largely to the United States. They go back to the late 1840s and the California Gold Rush. The first big wave of settlers into British Columbia was composed of bands of free-roaming miners, mostly American citizens, fresh from the unregulated killing fields of California.

As I have learned from books, from my parents and grandparents as well as from my own experience, there has consistently been a segment of BC’s settler society that, from its inception, has treated us essentially as those merciless Indian savages referred to in the American Declaration of Independence. The cultural roots of BC’s settler population go back largely to the United States. They go back to the late 1840s and the California Gold Rush. The first big wave of settlers into British Columbia was composed of bands of free-roaming miners, mostly American citizens, fresh from the unregulated killing fields of California.

On the mining frontiers of California the unrestrained vigilantism that the Royal Proclamation was meant to pre-empt gave rise to one of North America’s most grostesque episodes of ethnic cleansing. In the mid-nineteenth century miners murdered the Indigenous peoples of California wholesale. By and large these onslaughts of unregulated genocide were advanced with impunity. The perpetrators faced no legal consequences for their vigilante actions.

It is anyone’s guess if this faction would be powerful enough to pull British Columbia out of the Canadian federation if it ever happened that there was a real push backed by concerted political will at the highest level to resolve the issue of contested title to our ancestral lands and waters. Might the unfinished business of applying the Royal Proclamation to Canada’s westernmost province yet result in the inculcation of a secessionist movement similar to that which resulted in the creation of the United States? Might history repeat itself through a modern-day version of British North America’s division in 1776 as set in motion by settler rejection of the Indian provisions in the Royal Proclamation of 1763? Might settler resistance to Crown recognition and affirmation of existing Aboriginal and treaty rights in twenty-first century British Columbia yet result in the province’s secession from Canada in order to join the United States?

There has always been irony and paradox in our treatment, sometimes as worthy equals and sometimes as backward and primitive. Our treatment as subhumans lacking basic human rights was formalized beginning in the second half of the nineteenth century through the enactment by the Canadian parliament of various Indian Acts treating us as disenfranchised wards of the Dominion government. Among the Indian Act’s most harsh provisions were those that outlawed our traditional ceremonies. Moreover, between 1927 and 1951 the Indian Act was even extended to criminalize our efforts to develop political lobbies for the purpose of seeking Crown recognition of our Aboriginal and treaty rights.

One of the aims of this draconian prohibition was to prevent the Aboriginal peoples and our allies in British Columbia from gaining access to the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council (JCPC) in London England in the days when this agency was still the highest court in the British Empire. The fear was that the JCPC would apply an important precedent on Native title in the case of Amodu Tijani versus Southern Nigeria (Secretary) to the legal issue of unceded Aboriginal title to the lands, waters, and resources of British Columbia, including its prolific fish populations.

One of the aims of this draconian prohibition was to prevent the Aboriginal peoples and our allies in British Columbia from gaining access to the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council (JCPC) in London England in the days when this agency was still the highest court in the British Empire. The fear was that the JCPC would apply an important precedent on Native title in the case of Amodu Tijani versus Southern Nigeria (Secretary) to the legal issue of unceded Aboriginal title to the lands, waters, and resources of British Columbia, including its prolific fish populations.

In the period between the two world wars of the twentieth century federal and provincial authorities worked hand-in-hand to prevent Indian people in British Columbia from putting the issue of our unceded Aboriginal titles to much of BC in venues of genuine third-party adjudication. The abuses extended to withholding vital information from the key officials of the Allied Indian Tribes of British Columbia on the early history of contention over the content and scope of Aboriginal title, first in the British colony and then in the Canadian province of British Columbia.

This policy of concealment of supposedly public records was directed particularly at Andy  Paull and Rev. Peter Kelly, leading Aboriginal jurists of their day. As Paul Tennant has written in his treatise on The Indian Land Question in British Columbia, 1849-1989, “In their initial correspondence federal officials at times discussed the benefits of withholding information from Kelly and Paull, and the two were in fact prevented from obtaining a copy of the vitally informative Papers Connected with the Indian Land Question, the [provincial legislature’s] compilation of documents published in 1875 that provided the authoritative record of the land question’s early years.” [Paul Tennant, Aboriginal Peoples and Politics: The Indian Land Question in British Columbia, 1849-1989 (Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press, 1990), p. 102. See British Columbia Legislature, Papers Connected with the Indian Land Question, 1850-1875 (Victoria: Government Printer, 1875).

Paull and Rev. Peter Kelly, leading Aboriginal jurists of their day. As Paul Tennant has written in his treatise on The Indian Land Question in British Columbia, 1849-1989, “In their initial correspondence federal officials at times discussed the benefits of withholding information from Kelly and Paull, and the two were in fact prevented from obtaining a copy of the vitally informative Papers Connected with the Indian Land Question, the [provincial legislature’s] compilation of documents published in 1875 that provided the authoritative record of the land question’s early years.” [Paul Tennant, Aboriginal Peoples and Politics: The Indian Land Question in British Columbia, 1849-1989 (Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press, 1990), p. 102. See British Columbia Legislature, Papers Connected with the Indian Land Question, 1850-1875 (Victoria: Government Printer, 1875).

The case of Andy Paull is especially illustrative of the adaptations we Aboriginal peoples have had to make over generations to counter the many abuses of Canadian law. While these abuses have often been couched in the rhetoric of “emancipation,” the real goal has often been to advance our disempowerment and dispossession in order to clear the way for the further entitlement and enrichment of the settler population’s most influential sector.

A law clerk of considerable accomplishment, Paull held all the qualifications to become a lawyer. The Coast Salish jurist, however, refused to join the BC Bar because he would have had to give up his registered Indian status in order to become a Canadian lawyer. As a registered Indian subject to the infantilizing provisions of the Indian Act, Paull was prohibited from raising money for any Aboriginal claim without the permission of the Minister of Indian Affairs. Paull got around the virtual outlawing of pan-Aboriginal politics in Canada through his role as the coach of the North Shore Indians Lacrosse Team in the Vancouver area. This sports team, which included many Iroquoian lacrosse players especially from Ontario and Quebec, gave a nexus of organization to pan-Indian politics in an era when the government of Canada was most determined to control our lives with the ultimate goal of reducing the number of registered Indians to zero. [E. Palmer Patterson, Andrew Paull and the Canadian Indian Resurgence, Ph.D. Thesis, 1962; See Brian Titley, Duncan Campbell Scott and the Administration of Indian Affairs in Canada(Vancouver: UBC Press, 19920)]

As Allan Harper wrote of Canadian Indian policy in an international journal in 1945, “The ultimate end is ‘emancipation, ‘ i.e. the admission of Indian people into full citizenship and their biological absorption.” This combination of terms embodies a strange marriage of the language of liberation with that of cultural genocide. [Allan G. Harper, “Canada’s Indian Administration: Basic Concepts and Objectives,” America Indigena, Vol. 5, Vol. 2, 1945, p. 132] These internal tensions and contradictions have continued to plague Canada’s Aboriginal policies right up to the present day, when the imperatives of institutional assimilation have tended to replace the imperatives of cultural assimilation as advanced especially in the Church-run, federal financed Indian residential school system. A key moment of clarification occurred in 1969 with the decisive Aboriginal rejection of the assimilationist White Paper policy advanced in that era by Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau and his Indian Affairs Minister, Jean Chretien. [See Sally M. Weaver, Making Canadian Indian Policy: The Hidden Agenda, 1968-1970 (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1981)

President of the American Anthropological Association, Diamond Jenness was one of those social scientists who took a leading role in guiding the Canadian Indian Department during the mid-twentieth century. In 1945 Jenness was contracted by the Canadian government to come up with a scheme of educational integration calculated to, in the eerie language of that era, “liquidate Canada’s Indian problem in 25 years.” Jenness had earlier promoted this policy of termination based on his ethnocentric opinion that “culturally [the Indians of Canada] have already contributed everything that was valuable to our civilization.” [Peter Kulchyski, “Anthropology in the Service of the State: Diamond Jenness and Canadian Indian Policy,” Journal of Canadian Studies, Vol. 28, no. 2, 1993, pp. 33-38; Diamond Jenness, The Indians of Canada (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1932), p. 264]

Melvin H. Smith and Thomas Flanagan are prominent among those in Canada who have continued the Anglo-American assault on the constitutional heritage of the Royal Proclamation of 1763. A professorial mentor and sometime political advisor of Canadian Prime Minister Stephen Harper, Professor Flanagan has been hired repeatedly by the federal Ministry of Justice to advance arguments in court whose affect has been to deny and negate the existence of collectively-held Aboriginal and treaty rights. [Melvin H. Smith, Our Home Or Native Land: What Governments’ Aboriginal Policy Is Doing To Canada (Toronto: Stoddart Publishing, 1995); Thomas Flanagan, First Nations? Second Thoughts(Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2000)]

1.5 I, Kwitsel Tatel, a Sto:lo woman indigenous to the Fraser Valley, Demand Justifications for Infringements on those Existing Aboriginal and Treaty Rights Which Are Recognized and Affirmed in the Section 35 of Canada’s Constitution Act, 1982

Your Honour, I have described different facets, episodes, and periods of my life throughout this lengthy letter to initiate the second and constitutional phase of this trial. It seems that whenever we invoke those existing Aboriginal and treaty rights that are entrenched in the Canadian constitution there is a huge onus of proof on us to demonstrate and document many things, not only about ourselves as individuals but about our communities and our ancestors going back hundreds of years and even tens of thousands of years. Let me continue, then, by marking out a few features of who I am and what I have lived through.

I was born in 1963 to my parents, Rene Marjorie Kelly and Patrick (Buckshot) Kelly at our fishing camp at what is commonly called McDonald’s Landing at Leq’qamel reserve on the Fraser River. I was given the name Patricia Elaine Kelly by my parents. In more recent years the Halqe’meylem name, Kwitsel Tatel, was bestowed on me by a relative. The term translates into English as grizzly bear mother.

In my childhood I remember travelling regularly on the Fraser River between Musqueam and Yale. I was the second youngest of eleven surviving children. My registered Indian status number is 5790011701. Both my parents were of Sto:lo Coast Salish ancestry. Both died of alcohol-related ailments, my father when I was six years old and my mother when I was thirteen. Both were experienced fishers and hunters as were their parent and their parents before them back as far as we can remember. In learning from my parents and other family members about how my ancestors earned their living, I have heard plenty of references to fishing, logging, weaving, and cooking.

My siblings and I have grown up as Roman Catholics. I attended Catholic residential school in Mission BC where I faced regular bouts of sexual abuse from the school administrator. I have no hesitation in labeling as cultural genocide the combined efforts of church and state to push back our Halqe’meylem language and way of life through indoctrination disguised as religious schooling and through the outright outlawing of our traditional ceremonies. This prohibition touched the life of my maternal grandmother, Margaret Leon, who was made to do jail time after being convicted of Aboriginal dancing and singing.

I have attempted to retain and renew some remnants of our traditional political economy as fishers. I have some memories of our language and I continue to participate in some aspects of our previously-outlawed ceremonial practices. I also took advantage of educational opportunities to obtain a post-secondary degree at the University of the Fraser Valley. I have worked in a number of capacities including as treaty negotiator for my Leq’qmel band. I am a single mother of two teenagers, namely Kwiis Hamilton who is 18 and Sii-am Hamilton who is 17. The quality of our life together has deteriorated dramatically since 2004 when the federal Crown mounted its case against me for continuing to work the Aboriginal fisheries of my ancestors. This deterioration has been increasingly marked by poverty, extending sometimes to homelessness, as it became increasingly difficult for me to obtain and maintain gainful employment.

As I already noted, the inequities in the balance of power between our Aboriginal societies and that of our colonizers is marked in many ways, including in the different standards of proof that fall on us whenever the existing Aboriginal and treaty rights of the Aboriginal peoples of Canada come up for arbitration, as is the case here. It seems we are called upon again and again to prove who we are, where we came from, how we have changed or how we have stayed the same over time, and so on and so on and so on… It seems on the other hand that federal, provincial, corporate or private property owners now entrenched in our ancestral lands and waters are rarely called on to prove much about the sources of their claims to sovereignty, jurisdiction, ownership and such.

It is one of my goals to bring more equity to matters concerning the onus of proof in cases such as this one. As I shall explain and elaborate with copious references in the three parts of this letter to follow, I am demanding justification for 32 alleged infringements of “existing Aboriginal and treaty rights” that are “recognized and affirmed” in the Canadian constitution. These alleged infringements are as follows:

35 Alleged Infringements of Section 35

#1, Seizure and Selling of Fish Implying a Finding of Guilt Without Due Process

#2, Infringements on Constitutional Rights and Life Chances of a Single Mother’s Aboriginal Children

#3, The Placement of a Trial Concerning Areas of Federal Jurisdiction, Specifically Fish, Indians, and the Federal Crown’s Fiduciary Obligations to Aboriginal Peoples, in a BC Provincial Court

#4, Failure to Situate the Trial of Kwitsel Tatel in a Court with Sufficient Jurisdiction to Enforce Some Measure of Equity Between the Federal Prosecutor and the Defendant and the Failure to Situate the Trial in a Juridical Venue Equipped with the Necessary Jurisdiction to Define Human Rights, Including the Section 35 Rights of the Aboriginal Peoples of Canada

#5, Relegating the Arbitration of Constitutionally-Protected Rights That Are to Be Recognized and Affirmed to Processes Where a Primary Focus is on the Criminalization of the Aboriginal Peoples of Canada

#6, Inappropriate Crown Pressure Placed on Some Aboriginal People, including Kwitsel Tatel, to Plead Guilty to Criminal Charges for Activities That Might Be Exercises of Existing Aboriginal and Treaty Rights

#7, Failure of Crown Officials to Protect Section 35 Rights by Criminalizing Offenders That Violate These Rights

#8, Failure of Crown Officials to Provide Equitable Police Protection from Violent Incursions on the Very Persons of the Class of Peoples Covered by Section 35 of the Constitution Act, 1982

#9, Federal Failure to Rewrite the Fisheries Act to Conform with Section 35 and with the Unceded Aboriginal Rights of Those Aboriginal Groups, Especially in British Columbia, That Have Not Entered into Treaty Agreements with the Crown

#10, Failure of Law Enforcement Agencies in Canada to Develop Coherent Strategies and Policies for Comprehensive and Consistent Enforcement of Section 35

#11, The Dishonouring of the Crown by Crown Officials Who Deny and Negate Rather Than Recognize and Affirm the Existence of Aboriginal and Treaty Rights

#12, The Failure of the Federal Government of Canada to Resolve Conflicts Between Its Constitutional Responsibilities for Sea Coast and Inland Fisheries, Indians and Lands Reserved for the Indians, as well as for the Federal Crown’s Fiduciary Obligations to the Aboriginal Peoples of Canada

#13, The Consistent Failure of the Ministry of Justice to Uphold the Honour of the Crown by Recognizing and Affirming in Court the Existence of Aboriginal and Treaty Rights, including in the Trial of Kwitsel Tatel

#14, The Failure of the Federal Crown Prosecutor, Mr. Finn Jensen QC, to Reconcile Federal Power with Federal Duty by Attending to His Fiduciary Responsibilities to Help Kwitsel Tatel Receive a Fair Trial in a Juridical Venue Equipped with All Necessary Jurisdictional Capacities

#15, Failure of the Government of Canada to Mount Appropriate Training Programs Especially for Crown Officials Responsible for Applying, Enforcing and Safeguarding Section 35 Rights

#16, The Transformation of Crown-Aboriginal Alliances Built Up in the Defense of Canada into Crown-Aboriginal Antagonisms

#17, The Failure to Enforce Section 35 to Bring About More Equitable and Fair Apportionment of the Resource Wealth of Canada

#18, Failure of the Government of Canada to Come Up with a Clear Definition of Section 35 Sufficient to Provide a Rough Guide Outlining the Scope and Content of Existing Aboriginal and Treaty Rights

#19, The Failure to Reflect the Imperatives of Section 35 in the Constitution, Iconography, Staffing, Language Policies, Procedures and Conventions of Canada’s Courts

#20, The Inequity of the Juridical Process and the Failure of the Federal Crown to Live Up to Its Fiduciary Obligations to Mitigate at the Very Least the Resourcing Biases of an Unfair Trial [with particular reference to the responsibilities and alleged conflict of interest of Mr. Finn Jensen QC]

#21. Failure of Federal Crown Prosecutor, Mr. Finn Jensen QC, to Resolve the Conflict of Interest Attending His Responsibilities in the Kwitsel Tatel Case

#22, Lack of Transparency in Changes to the Charges Against Kwitsel Tatel and the Failure to Bring the Revised Charge into Conformity with the Principles Concerning Aboriginal Food Fisheries as Outlined in the Supreme Court’s Ruling in the Sparrow Case [with particular reference to Mr. Finn Jensen QC]

#23, Failure of Crown Officials to Address Seriously the Contentions of Kwitsel Tatel Concerning Section 35 Prior to Her Criminalization

#24, Discriminatory Enforcement of the Fisheries Act to Avoid the Criminalization of Non-Aboriginals in the Case of Kwitsel Tatel

#25, Wrongful Presumption of Guilt and Damaging Inaccuracies in the RCMP’s Publication of Patricia Kelly’s Crime Stopper’s Mug Shot and Personal Information

#26, Publication of Patricia Kelly’s Crime Stopper’s Advertisement as Propaganda for the Incitement of Racial or Ethnic Discrimination (See Article 8 of the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples)

#27, Mr. Finn Jensen’s Tactics on Behalf of the Federal Crown to Deny and Negate Section 35 Rights Through Plea Bargaining and through the Manipulation of Police Powers to Criminalize, Impoverish, Harrass, Dispossess, and Intimidate the Accused

#28, On the Failure of the Officers of the Chilliwack Law Courts to Provide Conditions of Safety, Security, and Respect for Canada’s Aboriginal and Multicultural Heritages

#29, The Failure of the Federal Ministry of Justice to Protect Section 35 by Pressing Criminal Charges Against Those That Violate Its Terms

#30, Section 4 of the Aboriginal Communal Fishing Licenses Regulations Confers on the Minister of Fisheries Powers That Are Inconsistent with Section 35

#31, The Accelerating Federal Retreat, Without Consultation with First Nations, from Conservation of Fish Habitat

#32, The Failure of the Federal and Provincial Governments to Safeguard and Protect From Pollution Those Natural Resources That Belong to the Aboriginal Peoples of Canada by Virtue of Section 35

#33, The Criminalization of Kwitsel Tatel Depends on a Statement of Facts That, in Reality, Contains Fictions

#34, Placing the Case of Kwitsel Tatel in a Court That Has the Full Authority to Criminalize the Accused but Which Lacks Jurisdiction to Define and Arbitrate Existing Aboriginal and Treaty Rights Under Section 35

#35, The Federal Ministry of Justice Has Improperly Directed the Trial of Kwitsel Tatel and Others of Its Type into the Provincial Court of British Columbia

Anthony Hall is a Professor of Globalization Studies at the University of Lethbridge in Alberta Canada where he has taught for 25 years. Along with Kevin Barrett, Tony is co-host of False Flag Weekly News at No Lies Radio Network. Prof. Hall is also Editor In Chief of the American Herald Tribune. His recent books include The American Empire and the Fourth World as well as Earth into Property: Colonization, Decolonization and Capitalism. Both are peered reviewed academic texts published by McGill-Queen’s University Press. Prof. Hall is a contributor to both books edited by Dr. Barrett on the two false flag shootings in Paris in 2015.

Part II was selected by The Independent in the UK as one of the best books of 2010. The journal of the American Library Association called Earth into Property “a scholarly tour de force.”

One of the book’s features is to set 9/11 and the 9/11 Wars in the context of global history since 1492.

ATTENTION READERS

We See The World From All Sides and Want YOU To Be Fully InformedIn fact, intentional disinformation is a disgraceful scourge in media today. So to assuage any possible errant incorrect information posted herein, we strongly encourage you to seek corroboration from other non-VT sources before forming an educated opinion.

About VT - Policies & Disclosures - Comment Policy