By Bruce Tyler Wick

Giving thanks to God, for one’s success in stealing from men, has been part of the American character from earliest times. In his weekly radio broadcast, “Sound of Majesty,” Greg Wheatley reads from Governor William Bradford’s journal, the “History of Plymouth Plantation,” for 25 November 1620.

On 21 November 1620; the Pilgrim Fathers had signed the Mayflower Compact on board the Mayflower, as the ship lay at anchor in Provincetown Harbor. Via the Mayflower Compact, the Pilgrims formed themselves into “a civil body politick” with governmental powers—in other words, they formed a municipal corporation.

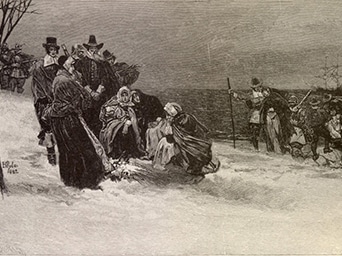

Thus organized, and four days later, 25 November 1620; a party of men set out from the Mayflower, in an attempt to make contact with the Indians. But those Indians, whom the Pilgrim party saw, ran away from them. William Bradford does not state the purpose of the Pilgrims’ intended outreach. But Greg Wheatley infers from the Pilgrims’ subsequent conduct, that the purpose was to obtain what Mr. Wheatley calls “provision” from the Indians.

So, it would seem; since once having found the Indians’ food, the Pilgrims evinced no further interest in finding the Indians themselves. Greg Wheatley read aloud from William Bradford’s journal, in Mr. Wheatley’s Thanksgiving Week broadcast this year of “Sound of Majesty”:

“And proceeding further [after finding a pond of clear, fresh water], they saw new stubble, where corn had been set the same year; also they found where lately a house had been, where some planks and a great kettle was remaining and heaps of sand newly paddled with their hands, which they, digging up, found in them divers fair Indian baskets filled with corn, and in some ears, fair and good of divers colors, which seemed to them a very goodly sight (having never seen any such before).”

Mr. Wheatley continued his reading with sentences not pertinent to the present inquiry, then concluded his recitation, as follows:

“So their time limited them being expired, they returned to the ship, lest they should be in fear of their safety; and took with them part of the corn, and buried up the rest, and so like the men of Eshcoll carried with them the fruits of the land, and showed their brethren; of which, and their return, they were marvelously glad and their hearts encouraged.”

Mr. Wheatley gives the date of the expedition described, as 1622—two years after the Pilgrim’s arrival at Cape Cod, with the intention of remaining there. But not finding the quotation among the pages devoted to 1622, and suspecting it a description of the Pilgrim’s “First Thanksgiving”; I looked for a date in November 1620, and found it as aforesaid, on 25 November 1620.

However, the last entry of William Bradford’s journal for 1622 shows the Pilgrims still lacking “provision.” Worse still, the “taking” of Indian corn in November 1620, which doubtless could have been justified as an emergency measure, and remedied as such, had since become a practice:

“After these things, in February: a messenger came from John Sanders, who was left chief of Mr. Weston’s men in the Bay of Massachusetts, who brought a letter showing the great wants they were fallen into; and he would have borrowed a [quantity abbreviation] of corn of the Indians, but they would lend him none.

He desired advice, whether he might take it from them by force to succor his men, till he came from the eastward, whither he was going. The Governor and the rest dissuaded him by all means from it, for it might so exasperate the Indians, as might endanger their safety, and all of us might smart for it; for they had already heard how they had so wronged the Indians by stealing their corn, etc., as they were much incensed against them.

Yea, so base were some of their own company, as they went and told the Indians that their Governor was proposed to come and take the corn by force. The which, with other things, made them enter into a conspiracy against the English, of which more in the next. Herewith, I end this year.”

Now, the Mayflower Compact itself makes no mention of Indians, much less “Indian Affairs.” Yet, the expedition from the ship, a mere four days after signing, strongly suggests “Indian Affairs” were uppermost; and that the new corporation expected to treat with the Indians, as one “tribe” to another.

Indeed, the Pilgrims’ very survival that coming winter (1620-21), and for the several to follow, might depend upon the indigenous peoples of the area—and how well or how badly disposed they were towards the Pilgrims and their settlement venture.

After veering wildly off course, the Mayflower had carried the Pilgrims far north of their intended destination, northern Virginia, where they had intended to settle. On 19 November 1620, the ship sighted land—Cape Cod in Massachusetts. After several days of trying to sail south to Virginia, strong winter seas forced the ship to return to the harbor at Cape Cod, where it anchored 21 November 1620. The Mayflower Compact was signed that same day.

According to MayflowerHistory.com, the Mayflower Compact,

“was drawn up in response to ‘mutinous speeches’ that had come about because the Pilgrims had intended to settle in Northern Virginia, but the decision was made after arrival to instead settle in New England. Since there was no government in place, some felt they had no legal obligation to remain within the colony and supply their labor. The Mayflower Compact attempted to temporarily establish that government until a more official one could be drawn up in England that would give them the right to self-govern themselves in New England.”

Yet, in planning the proposed Virginia settlement, little thought seems to have been given to the Pilgrims’ relations with the indigenous peoples of Virginia. Rapid population growth, and consequent westward expansion, apparently, were expected to solve all difficulties—whether in Virginia or in other English settlements.

And so we find, much later, the Continental Congress, complaining in its Declaration of Independence, that—

“[George III] has endeavored to prevent the population of these States; for that purpose obstructing the laws for naturalization of foreigners; refusing to pass others to encourage their immigration hither, and raising the conditions of new appropriations of lands.”

New appropriations of lands? What lands?

By 1776, Indians were enemies. From that same Declaration of Independence:

“[George III] has excited domestic insurrections amongst us, and has endeavored to bring on the inhabitants of our frontiers, the merciless Indian savages, whose known rule of warfare, is an undistinguished destruction of all ages, sexes and conditions.”

I recall an Indian military client, who when I arrived at Fort Leavenworth to interview him, was on the phone with his Tribe’s Chief, or perhaps its Medicineman. On being introduced, I inquired if he were one of the “merciless Indian savages” I’d been reading about. He’d never seen the reference in the Declaration of Independence.

24 November 2012

BRUCE TYLER WICKis a lawyer and registered parliamentarian, who practices mainly in northeast Ohio.

BRUCE TYLER WICK is a lawyer and registered parliamentarian, who practices mainly in northeast Ohio.

Attorney Wick’s work with serving the military and with veterans has involved principally criminal defense and appeals; clemency, parole and administrative matters; and VA claims.

A student of legal history in the tradition of his teacher, Samuel Sonnenfield, Attorney Wick claims first and exclusive authority for discovering that Ohio’s Constitutional Convention of 1802 granted the right to vote to black men over 21. That advance, though epochal, was quickly taken away by fraud.

ATTENTION READERS

We See The World From All Sides and Want YOU To Be Fully InformedIn fact, intentional disinformation is a disgraceful scourge in media today. So to assuage any possible errant incorrect information posted herein, we strongly encourage you to seek corroboration from other non-VT sources before forming an educated opinion.

About VT - Policies & Disclosures - Comment Policy