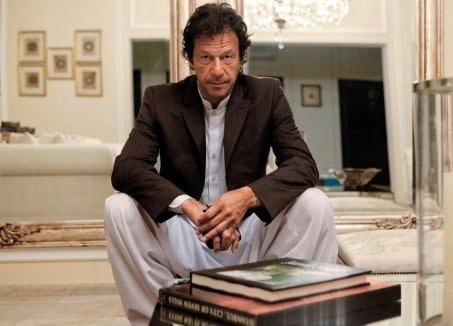

Playboy, sports star—and possibly Pakistan’s next prime minister.

Playboy, sports star—and possibly Pakistan’s next prime minister.

Stuffed into the driver’s seat of his silver Land Cruiser, Imran Khan, the cricket sensation and possible next prime minister of Pakistan, careens wildly through the Punjab night around livestock and Mack trucks tricked out with trinkets.

His is the most recognizable face in Pakistan yet Khan speeds unnoticed past pickup beds and rickshaws full of constituents, swerving into oncoming traffic and along the shoulder of the road.

When two women from the wheat fields appear suddenly in his high beams, Khan finally flinches, jams the brakes, cuts the wheel, and then squeezes his SUV between them with just inches to spare. He quickly collects himself. “You need good reflexes,” he says.

[youtube GF00BtlBqMI]

As if it were an easy win in a cricket match, Khan predicts that his centrist party, the Pakistan Movement for Justice, can fix the country’s problems in just 90 days. But his strategy for dealing with the Taliban and other Islamic militants has led to charges that he is soft on extremists. His plan is to order the Army to withdraw from the unruly tribal areas and start a dialogue with the militants.

To him the war in Afghanistan and on the Pakistan border conforms to “Einstein’s definition of madness: doing the same thing over and over again and expecting a different result … The Pakistan Army is killing its own people. It’s the most shameful period in our history. We created militants through collateral damage, and we are creating more militants through collateral damage. It’s a ruling elite which sold its soul for dollars.”

Beyond ending the fighting in the border area, his campaign is built on the twin promises of battling corruption and standing up to the American administration, which puts him in the interesting political position that the worse things get in his country, and the further U.S.-Pakistan relations deteriorate, the better for him.

[youtube dT6JATLwjqY]

“The disenchantment with the other political parties is so acute, and that’s the space that has been carved for Imran Khan,” says Jugnu Mohsin, publisher of The Friday Times, an independent weekly based in Lahore, and a frequent Khan critic. When asked what kind of president he would make, her response is visceral. “I shudder to think because he is a man who doesn’t really have a firm grip on history, or politics, or economy,” she says. “He would be very easily led and misled … And I think the military would probably continue to call the shots.”

Khan’s campaign is funded by Pakistani businessmen, and supported by the middle class and the young, along with many right-wing voters who “choose not to vote for a religious party but want more or less the same policies,” according to Hasan-Askari Rizvi, an analyst based in Lahore.

Mohsin and other observers have also suggested that Khan is secretly propped up by the military and Pakistan’s notorious spy agency, the Directorate for Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI). Khan himself denies any clandestine connections and Hamid Gul, the former director of the ISI widely considered the “father of the Taliban,” says that although some security forces have sympathy for Khan, he doesn’t think that Khan takes their orders. “Many individuals might support him, but that’s individuals.”

When asked whether he believes the Pakistan Army or the intelligence brass knew about Osama bin Laden hiding out in Pakistan, Khan says they had little to gain and much to lose, though he does think it’s possible that lower-level officers played a role. And he is quick to criticize the killing of bin Laden, which inspired a “total sense of humiliation” among Pakistanis, he says. “Rather than shooting him, they should have picked him up,” he says. “Here’s a country that’s lost 35,000 troops in your war. Are we an ally or not?”

His populist rhetoric has often been aimed at the U.S., and he is dismissive of President Barack Obama, whom he describes as “intelligent” but without “the strength to take those big decisions which we were all hoping he would.” Some commentators have described him as anti-American—a charge he denies. “I guess they call me anti-American because slaves are not supposed to disagree with the policies of the masters.”

Such tough talk has lifted him in the polls—the last survey showed an approval rating of about 68 percent—but Pakistan, like Britain, has a parliamentary system, requiring his untested party to win broadly across the country. It may be his moment. Almost 60 percent of Pakistan’s population is under 25, and they are sick of the status quo: the military’s grip on power, tired political dynasties, and a lack of economic opportunity. “Pakistanis want a way out of this,” says Maleeha Lodhi, former ambassador to the U.S. and Britain, and an influential supporter and confidante. “The election is his to lose.”

His father hailed from poor and rural Mianwali, but Khan was bred in Lahore prep schools and has a degree in philosophy, politics, and economics from Oxford University. On the cricket pitch, Khan captained Pakistan to its first and only World Cup victory, in 1992, and was considered the sport’s top athlete. His testosterone-charged exploits in London drew almost as much attention, and even now Khan can’t suppress a red-blooded boast about his bachelor days:

“Don’t forget, I was the No. 1 cricketer in the world at the time.” Romantically tied to Goldie Hawn, among many others, he was also a close friend of Mick Jagger and Princess Diana. “He obviously had this great playboy reputation, and he was gorgeous,” says a former girlfriend, adding, “When you’re with him, he’s very much with you.” (She says that during “intimate moments” he “growled like a tiger.”)

Khan still has his lean good looks and trademark feathered haircut, though there’s a just-visible bald spot on his head and his sideburns have hints of gray. On this evening, his two sons, 15-year-old Sulaiman and 12-year-old Kasim, are visiting from London, where they live with their mother, the British journalist and heiress Jemima Khan (née Goldsmith).

When she and Khan married in 1995, she was a golden-haired 21-year-old “it” girl, and he was just about to begin his transformation from national sports hero to politician. They moved to Lahore and, in 1996, Khan founded his political party, donated much of his money to charity, and began campaigning. Jemima, meanwhile, converted to Islam, learned Urdu, championed Pakistani causes, and lived in what was described as a cramped place with “grimy sofas.”

Khan raised money for a cancer hospital in Lahore for the many poor who couldn’t afford specialized treatment. When it opened in 1994, he named it the Shaukat Khanum Memorial Cancer Hospital & Research Centre, after his mother, who died of colon cancer in 1985 at the age of 63. Two years later, political enemies of Khan bombed the hospital in a blast that killed eight people and injured 30. Khan was scheduled to visit but hadn’t yet arrived, and so was unscathed.

For the glamorous couple, life had clearly taken a harder turn, and Khan was often away from his family.

“There was a lot of time spent apart and, more importantly, there was just an endless sense of being a kind of terrible Achilles’ heel, because every time there was an election campaign, there’d be something else about me that would be used to discredit him,” Jemima says today, adding that smears and death threats were constant. People would even call and tell her that Khan was dead. “It was tense. He used to go for walks with his dogs with a big gun on his waist … It became clear in the last campaign that I was better off just not being involved.”

In 2002, he was elected to Parliament. Two years later, the couple had divorced.

By then Khan had established himself as a devout Muslim. He’s now so close to the religious right that critics call him “Taliban without a beard.” (During a recent spat, Salman Rushdie described him as “a better-looking Gaddafi.”)

But in Pakistan, both religious parties and the militants remain suspicious of him. Mullah Malang, a Taliban commander, describes him as one of the “usual U.S. puppet politicians of Pakistan.” “His track record is full of sins and scandals,” the commander says. “If he was a good Pakistani and practicing Muslim, he wouldn’t have married an English Jewish girl.” Jemima (who’s not Jewish) disagrees with those who say he’s a phony. “He has all sorts of bits in him—a bit like Pakistan. He’s very complicated and conflicted.”

And, in Pakistan, a man with his past must walk a very fine line.

Khan “has been careful not to make any statements that would antagonize the extremists,” says Talat Masood, a retired lieutenant general who now comments on Pakistani politics. “His policies and manifestos converse well with the Taliban. He has always pushed for talks and peace deals with the Taliban. Let me put it this way: he avoids taking them on. I think he has learned from Benazir Bhutto’s example. She took a strong stance against the extremists and suffered as a result. He does not want to be targeted; neither does he want to lose the conservative vote.”

This may be Khan’s moment as people look for change in a country that has gone through five finance ministers in the last four years, a place where trash doesn’t get picked up, power outages are frequent, and where teachers, nurses, and police don’t get paid. But Khan’s plans for dealing with economic mismanagement and endemic corruption are vague, and even Gul, the former ISI chief and an early mentor for Khan, is unconvinced. “What change is he going to bring? He has been focusing his attention only on corruption. But there are more structural changes required in Pakistan.”

When asked about Khan becoming prime minister, his ex-wife says: “I’m conflicted because, on the one hand, I don’t want my children’s father to put himself into a position that’s very dangerous … but at the same time, part of me wants him to be successful, not just for him and for Pakistan, but also because it makes sense of some of the really big sacrifices that he did make, and one of those was his family life. You know, if he’s not successful, there’s a point at which you ask, ‘What were all those sacrifices for?’ ”

At one campaign stop, Khan sat like a king as excited locals pressed around him. Big bowls of chicken and mutton were placed before him. While his aides ate with forks, Khan dug his big fingers right into the bowls—in the traditional way of eating. Once the meal was over, however, the celebratory mood shifted as people shouted complaints and needs: a new hospital, a better primary school. It was late in the afternoon, and Khan seemed exasperated as he put up his hands. “When the Movement for Justice is in power, I will take care of these problems,” he finally said, then got back into his Land Cruiser and sped away.

With reporting by Jahanzeb Aslam, Sami Yousafzai, and Nazar Ul Islam.

ATTENTION READERS

We See The World From All Sides and Want YOU To Be Fully InformedIn fact, intentional disinformation is a disgraceful scourge in media today. So to assuage any possible errant incorrect information posted herein, we strongly encourage you to seek corroboration from other non-VT sources before forming an educated opinion.

About VT - Policies & Disclosures - Comment Policy