by Ken Ward Jr

CHARLESTON, W.Va. — As the trial begins in a major toxic pollution lawsuit against Monsanto Co., jurors won’t be allowed to tackle a key issue: Should the company pay to clean up dioxin it allegedly spewed across the city of Nitro?

Experts won’t testify about the need for property remediation. Lawyers won’t argue about the issue. Jurors won’t be asked to force Monsanto to spend the hundreds of millions of dollars such a project could cost.

Judges O.C. Spaulding and Derek Swope issued rulings in July and November that threw out that part of the case.

As a result, Putnam County jurors will decide only if current and former Nitro residents should receive medical monitoring to detect diseases potentially caused by exposure to Monsanto’s dioxin. They won’t be able to do anything to clean up homes and businesses, ending the toxic exposure.

Lawyers for thousands of residents and property owners in the class-action suit appealed the decisions by Spaulding and Swope. They say the rulings left a huge gap in their efforts to deal with the legacy of Monsanto’s chemical-making operations.

“The current presence of dioxin contamination in the class area is a public-health hazard,” the lawyers argued in court documents. “It makes little sense to initiate a medical monitoring program for a population without first eliminating that population’s exposure to the toxin at issue.”

The West Virginia Supreme Court isn’t likely to even begin considering the appeal until April. By the time a decision is made, the trial on the medical monitoring question will probably be over.

The situation has left insiders and observers scratching their heads, as lawyers for Monsanto and Nitro residents prepare to head into one of the biggest civil trials in the Kanawha Valley in years.

“It doesn’t make any sense from the standpoint of the impact on the community,” said longtime Nitro lawyer Harvey Peyton.

Peyton is a former law partner of Charleston attorney Stuart Calwell, who is the lead lawyer for Nitro residents in the case.

Twenty-eight years ago, Calwell and Peyton were among the lawyers who lost in a landmark effort to get jurors to hold Monsanto responsible for dioxin-linked illnesses among Nitro plant workers.

Today, the science showing dioxin’s dangers is much more advanced. The law has created some new ways — such as medical monitoring cases — to address these issues. Industry has also gotten much better at fighting citizen and worker lawsuits, and at the lobbying and public relations efforts that can block tougher regulations or expensive cleanups.

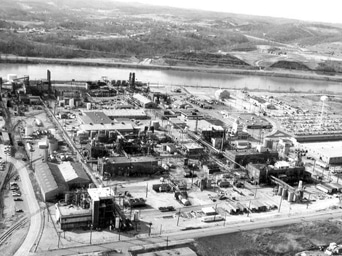

For decades, chemical plants like Monsanto’s provided Kanawha Valley residents with thousands of good-paying jobs. The industry has been in a long decline, and the bulk of those jobs have disappeared. The Monsanto plant went through several ownership changes and then closed in 2004.

Generations of workers put food on their tables and sent kids to college with a chemical plant paycheck. But the industry’s legacy also includes tough questions about long-term health effects on workers and plant neighbors.

More than 40 years after Monsanto stopped making 2,4,5-T, the Agent Orange ingredient blamed for much of the plant’s dioxin pollution, it’s not clear if Nitro residents are any closer to getting answers to such questions.

In the beginning

Nitro was born as a literal World War I boomtown, the location of one of the federal government’s large gunpowder plants. The name “Nitro” came from the chemical term Nitro-Cellulose, which was the type of gunpowder to be produced.

When the war ended, private companies took over the government buildings and converted them into chemical plants. Among the companies was Monsanto, which began making rubber chemicals for the tire industry.

In about 1947, Monsanto’s agricultural division designed a new molecule called 2,4,5-trichlorophenoxyacidic acid, or 2,4,5-T. This new substances killed plants by making their roots outgrow their leaves. Plants destroyed themselves through defoliation.

Monsanto began making this powerful herbicide ingredient in Nitro in 1949. Workers cooked batches of it in large pots, called autoclaves, rather than making it through a continuous production stream.

Monsanto made 2,4,5-T in Nitro for more than 30 years. In its best-known form, 2,4,5-T was used as an ingredient in Agent Orange, the defoliant deployed widely in the Vietnam War.

But 2,4-5-T was contaminated. Every batch of it contained 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-para-dioxin. This chemical is also known as 2,3,7,8-TCDD, or more commonly, simply as dioxin.

Dioxin has been linked to cancer, birth defects, learning disabilities, endometriosis, infertility, and suppressed immune functions. The chemical builds up in tissue over time, meaning that even small exposures can accumulate to dangerous levels.

An early sign of dioxin’s effects came in March 1949. A massive explosion rocked the Nitro plant when a pressure valve blew on a 2,4,5-T cooking container. More than 220 workers got sick.

Years later, more than 170 workers sued Monsanto, alleging dioxin exposure at the plant had made them ill. Cases involving seven of the workers went to trial in federal court in 1984.

After an 11-month trial, a jury awarded one of the workers, John Hein, $200,000 for bladder cancer he contracted because of exposure at the plant to another chemical, para-aminobiphynol, or PAB.

Jurors found that dioxin had made the other workers sick and that Monsanto had not acted diligently in seeking to determine the possible impact of exposure on worker health.

ATTENTION READERS

We See The World From All Sides and Want YOU To Be Fully InformedIn fact, intentional disinformation is a disgraceful scourge in media today. So to assuage any possible errant incorrect information posted herein, we strongly encourage you to seek corroboration from other non-VT sources before forming an educated opinion.

About VT - Policies & Disclosures - Comment Policy