The CIA, George Bush, MKUltra, LSD, Scientology, James Earl Ray, John Lennon, Mark David Chapman, Artie Bremer, the Unabomber

…They’re all Here

by Trowbridge H. Ford edited by Jim W. Dean

The contrast behind the myth and reality regarding the health of American democracy when President Jimmy Carter sought re-election in 1980 could not have been greater.

The liberals and responsible conservatives who had brought about the resignation of the rampaging Nixon thought that constitutional government had been restored, or at least secret government had been significantly reined in.

But actual conditions, despite appearances, had become worse thanks to leaders of covert rule finding new ways to perform old operations.

The CIA had been slimmed down, particularly the Operations Directorate where the adoption of more technical means for the collection of intelligence, and through the retirement and death for some of the worst offenders – especially former DCI Richard Helms, CI chief James Angleton, and “Executive Action’s” William King Harvey.

But that process had been more than compensated by old troublemakers finding new homes in other agencies, current ones finding ways to operate behind the backs of their nominal superiors, and old agent capability, especially in the production of mind-control, obtaining new technology and candidates for covert operations.

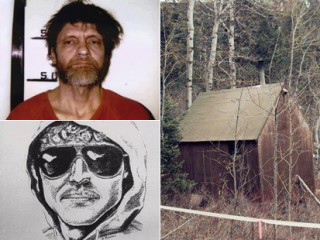

The Secret Team’s, to use Colonel L. Fletcher Prouty’s terminology, hopes that Theodore Kaczynski (aka the Unabomber) had the makings of a perfect Manchurian Candidate for killing President Carter’s re-election chances, despite promising testing, proved unfounded.

Kaczynski, though connected to all the right people while at Berkeley at the end of the 1960s through Colston Westbrook’s Black Cultural Association, was not politically motivated enough to become a predictable robot.

The loner mathematician, while he was finally recruited from Montana where no skeptics would suspect CIA involvement, was not willing to go after targets it had in mind, no matter how hard his co-conspirator brother David drove him, or how much drugs he was given.

Ted Kaczynski had it in for university colleagues, especially those who supported the build-up of technology the Agency was interested in, and air lines which permitted them to experiment all around the world, as his FBI code name prefix indicated.

The Unabomber showed his unreliable character in the wake of the failed hostage rescue mission in Iran (Operation Eagle Claw) by following up his attack on an American Airline flight to Washington with a crude bomb sent to United Air Line president Percy Wood on June 9, 1980.

Kaczynski set Wood up by writing first in the name of Enoch W. Fischer, recommending that he, and other leaders of the capitalist world read Sloan Wilson’s new book, Ice Brothers, which would be arriving in a separate wrapper.

This nostalgic account by Wilson – the author also of best-selling The Man in the Grey Flannel Suit – of his service during WWII in the Greenland Patrol was a telling reminder of just how far the author and Kaczynski had fallen out with their wartime buddies.

This was particularly the case with Ted’s most ambitious brother David in the post-war grab for personal glory.

For those interested in pursuing red-herrings on the internet about the book, see Ross Getman’s website where he claims that Kaczynski, a neo-Nazi, found inspiration for his anti-Semitism in its pages.

Characteristically, the Bureau questioned Sloan rather than David Kaczynski about the book’s significance, once the Unabomber was finally caught.

Ronald Reagan’s biggest contribution to the covert campaign against Carter’s re-election then became the expertise that Dr. Earl Brian, his former Secretary of Health, supplied for mind-control operations.

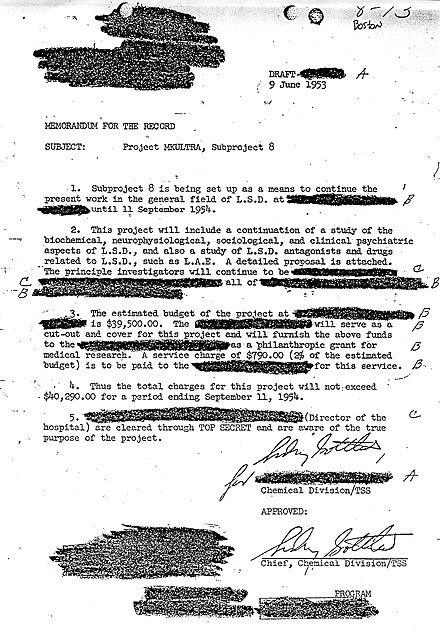

The CIA’s Dr. George White, had been obliged officially to close down experiments in California, and former head of the Technical Services Staff Dr. Sidney Gottlieb was driven to convenient suicide because of legal questions arising in 1979 about painter Stanley Milton Glickman’s incapacity, another unwitting CIA guinea pig from a quarter century before in Paris.

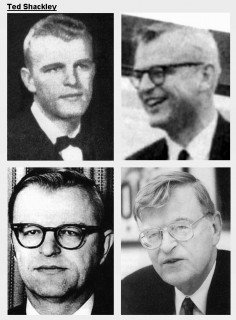

Brian, like George Bush, Theodore Shackley, and William Casey, would ultimately be linked to the “October Surprise”, and the Reagan Justice Department’s theft of PROMIS software from Bill Hamilton’s INSLAW company to keep track of foreign counterintelligence (Jonathan Vankin and John Whelan, The 60 Greatest Conspiracies of All Time, p. 119ff.).

But actually Dr. Brian, like White and Gottlieb, was most closely connected to “LSD surprises”, what had led to tennis professional Harold Blauer’s death from forced injections, and Dr. Frank Olson’s most suspicious death in 1953.

Brian even tried to establish in 1975, with Governor Reagan’s support, a center for the study of violent behavior in the Santa Monica Mountains, what would permit all kinds of mind-control operations with complete secrecy under UCLA professor Dr. Louis “Jolly” West’s leadership, but the fallout from Watergate prevented the California legislature from authorizing such a reckless initiative.

West – as Henry Martin and David Caul indicated in a long 1991 series about the state’s continuing mind-control program for the Napa Sentinel – was a product of the University of Minnesota’s Morse Allen, the leading expert on making Manchurian Candidates.

He had worked at Oklahoma for 15 years with John Gittinger, the developer of the crucial Personal Assessment System for finding potential ones. ( For more, see obituary, “Louis Jolyon ‘Jolly’ West,” The Los Angeles Times, Jan. 7, 1999.)

At Oklahoma, West, as John Marks indicated in The Search for the ‘Manchurian Candidate, became the leading recipient of secret funding for LSD experimentation (p. 63), what ultimately led to certain people being programmed with sufficient doses of the drug not only to betray their countries but also their families, even their spouses.

LSD, in an operational setting, could make the patient into a paranoid madman, set on destroying his marriage and memory.

Coming to UCLA in 1968, just after the assassinations of MLK and RFK, West was very successful in securing grants, over $5 million for himself from the National Institutes of Mental Health, and as much as $14 million in a single year for his Neuropsychiatric Institute from a wide range of sources.

He used these for conducting experiments on controlling allegedly violent individuals – what gave all kinds of opportunities for creating them through the assistance of cooperating, professional informants.

Though West feigned to be a great civil libertarian, and made a point of providing free expert opinion in public interest cases (See his letter in the June 24, 1976 issue of The New York Review of Books about Patty Hearst’s unsuccessful defense.), he, and side kick Dr. “Oz” Janiger, were such pavlovians when it came to drugs that Aldous Huxley, the greatest proponent of LSD’s liberating qualities, could not abide their obsessions. (See Huxley’s June 6, 1961 letter to Timothy Leary.)

In 1966, LSD was prohibited by the Drug Abuse Control Amendment from being used in experiments, causing the FDA to raid Janiger’s office in Beverly Hills, and to confiscate all his drugs, and records of clinical research.

“When the panic subsided, only five government-approved scientists were allowed to continue LSD research…,” Todd Brendan Fahey wrote in the Las Vegas Weekly, the leading one being West. Until then, Janiger had gotten LSD from people like the CIA’s Captain Al Hubbard for his experiments on those who wanted to improve their performance, especially among Hollywood’s actors, notably Cary Grant.

Now Janiger would get it from West, and, in return, he would be given access to his most promising subjects.

This came in most handy in 1977 when The Washington Post reported that the scientific assistant to Carter’s Navy Secretary, Dr. Sam Koslov, had ended the program that West was running out of Stanford’s Research Institute at Fort Meade to create Manchurian Candidates by electronic means (“The Constantine Report No1,”).

This apparently left only the old means of deprivation, drugs, psychic driving, and hypnosis for making people with multiple personalities into their Neo-Assassins.

West’s greatest asset was that he was now interested in cults, the ideal cover for anyone who wanted to continue practicing “brain-washing” by CIA’s more traditional methods.

In the wake of Charles Manson’s murders, Patty Hearst’s kidnapping and brain-washing by the Symbionese Liberation Army, and the massacre/suicide of 913 cultists at Jonestown, Guyana in 1978, the public was prepared to believe that such brain-washing was only the result of thought reform which the CIA had apparently helped sponsor with drugs in order to make sure that student radicalism spun out of control in utter confusion.

To legitimize the idea of coercive persuasion, West’s associate Dr. Margaret Singer wrote a ground-breaking paper the following year on the new phenomenon (“Dr. Margaret Singer’s 6 Conditions for Thought Reform,” csj.org/studyindex), and she and Yale’s Dr. Robert Jay Lifton started propagating the claims as advisory board psychologists to the new American Family Foundation.

Singer and Lifton had studied the brain-washing techniques on Amercian POWs by the North Koreans for Washington back in the ‘fifties, ruling out wrongly their drug, and hypnosis-based techniques – what West used heavy doses of LSD-25, and hypnotism to replicate. (Jeffrey Steinberg, “Who Are the American Family Foundation Mind-Controllers Targeting LaRouche?,” Executive Intelligence Review, April 19, 2002, and larouche pub.com/other/2002)

During August 1980, Reagan’s campaign managers, especially pollster Richard Werthlin, Georgetown professor Richard Allen, and former CIA agent Richard Beal, organized a special operations group to counter any Carter “October Surprise” – the only thing they thought would secure his re-election.

At the same time, John Hinckley, Jr. was programmed to assassinate President Carter just in case he was able to secure the release of the hostages by negotiation – what these people, along with Marine Captain Oliver North and Colonel Robert MacFarlane – had been able to prevent by force.

The operation’s attraction lay in the fact that despite the publication of John Marks’s book on Manchurian Candidates the previous year, only Milton Kline, onetime President of the American Society for Clinical and Experimental Hypnosis, and sometime CIA consultant in actual operations, believed that patsies and assassins could be, and had been created on occasion. (p. 199ff., esp. 204, note.)

Hinckley, one of the Beat Generation, was the offspring of an upward-mobile, disassociated family, growing up in Dallas during the years before the JFK assassination and during its aftermath.

While his older brother Scott was following in his father’s footsteps at the Agency-connected Vanderbilt Energy Corporation, John was having trouble even getting started, spending seven years, on and off, at Texas Tech but without success.

About the only thing he picked up was how to play the guitar, and an inclination for acting.

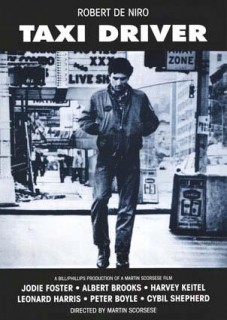

During a trip to Hollywood in 1976, he came across Dr. Janiger, it seems, and was soon taking LSD again, and watching incessantly Martin Scorsese’s film Taxi Driver, based on the life of George Wallace assassin Arthur Bremer, in the hope of becoming a successful actor.

Before it was over, he imagined that he had become Robert Di Niro’s alter ego. (“John W. Hinckley, Jr.: A Biography,” law.unkc.edu/faculty/proje…)

Hinckley was so convinced that he was a carbon copy of the alienated, drugged cabbie that he even fantasized, it seems, that he too had a girl friend, like Betsy in the film, working in a campaign for a politician he ultimately plotted to kill in order to impress her, calling her Lynn Collins.

The only trouble with this propensity was that there was no need for it now in Agency operations as critics like Senator Frank Church were finished off early by the electorate, among other things, because of their attacks on America’s covert government.

Hardly had the unknown Carter gotten established in the White House than Hinckley was back in Hollywood a year later for more.

The trouble with Hinckley’s potential was that the new President was proving much more supportive of the plans by secret government than any one had imagined (See, e. g., Sherry Sontag and Christopher Drew, Blind Man’s Bluff, p. 294ff.), and making Walter Mondale, the most experienced politician in keeping the intelligence community in check, President would only compound problems with its critics.

Consequently, Hinckley’s handler, and it seems to have been either Dr. Singer or one of her female associates, directed him towards more beneficial activity, leading apparently to his gaining a role in a play, and becoming romantically attached to an actress, a daughter of the mother of all conspiracy theorists, Mae Brussell, of all people.

“Brussell,” Vankin and Whelan have written, thought that this well-heeled individual without any visible means of support “…might be an ‘agent provocateur’ directed against her by the FBI via her daughter.” (p. 66)

Then, as when Jules Ricco Kimble aka Raoul thought that Harvey was pursuing him in New Orleans in 1967, and called the Domestic Contact agent to protest, she called the Bureau’s Monterey Resident Agent to complain, making herself likewise a possible suspect in future developments.

Ms. Brussell, thanks to financial support from the John Lennons, and publication support from The Realist’s Paul Krassner, was becoming increasingly convinced that Governor Reagan was to be the beneficiary of all the ongoing ‘dirty tricks’. (Paul Krassner, Confessions of a raving, unconformed nut, pp. 213-5)

Once the summer season was over, Hinckley returned to Texas Tech with a new lease on life for the stage, changing his major from business administration to English to suit his new career goals, only to see his relationship with Mae’s daughter ended, apparently because the mother opposed it, possibly resulting in the daughter’s death in an automobile accident.

In a tailspin, Hinckley helped young George W. Bush in his unsuccessful 1978 run, directed by brother Neil, for the House seat in Lubbock, a campaign which Hinckley’s parents contributed money to. When it too proved unsuccessful, Hinckley went completely off the rails.

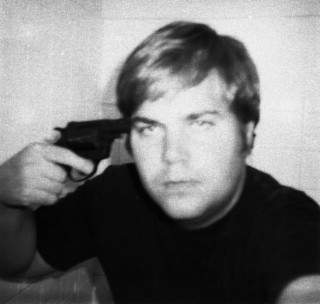

He played Russian roulette with a .38 pistol he bought in August 1979, as he began to experience all kinds of aliments, requiring him to seek professional help, and to take both anti-depressants and tranquilizers, talltail signs of a manic depressive in a stretched out state.

Hinckley even anticipated his role as Carter’s assassin in March 1980, before his handlers had even decided upon it, by stalking him on his own during his early campaigning.

Once the Reagan campaign against Carter moved into gear, and his assassination was now a distinct possibility, Hinckley spent three weeks during September enrolled at Yale, stalking actress Jodi Foster who played the teenage prostitute, Iris, in the movie.

It was a classic case of negative psychic driving where the candidate would have experiences, and emotional reactions which would spur him on to more threatening actions.

James Earl Ray experienced this after he attended dancing classes, graduated from bartending school, underwent a nose job, joined a Swinger’s Club, and advertized his sexual prowess in the Los Angeles Free Press but to no avail. (Gerald Posner, Killing the Dream, p. 208ff., though n.b. that he did not see hypnosis by Dr. Xavier von Koss as the cause.)

As Hinckley wrote Foster, perhaps a bit too self-consciously, just before he set off on his final mission to shoot Reagan:

“And by hanging around your dormitory, I’ve come to realize that I’m the topic of more than a little conversation, however full of ridicule it may be.” (evidence in U.S. v. John W. Hinckley, Jr.)

“In a three-day period, Hinckley visited three cities where Carter rallies were held: Washington, D. C., Columbus, and Dayton.” (Doug Linders, “The Trial of John W. Hinckley, Jr.”) Though he once got within 20 feet of the President, he wasn’t able to draw his pistol, and shoot, claiming cryptically that he wasn’t in the proper frame of mind.

Actually, the President hadn’t made a surprise announcement about the hostages which would have triggered the shooting, like what RFK’s announcement caused after he won the California primary.

Then trips by Hinckley to Lincoln, Nashville, Dallas, Washington, and Denver proved no more efficacious, thanks to the apparent failure of a leading Nazi to stiffen his nerve, to a tip off to airport authorities about a pistol in his luggage, and the like.

Hinckley’s defense, if he had been pushed to shoot Carter, would have been that he was such a rabid supporter of the Reagan-Bush ticket, thanks particularly to all his connections with the Vice President’s family, that he could not restrain himself when the President stole the election by completely underhanded means because of Mae Brussell’s hatred of Reagan and his supporters.

Just when all Hinckley’s stalking had apparently proven unnecessary – Reagan’s campaign officials concluded that Tehran’s consultations with Carter’s Iranian Core Group had ended in failure.

Bush received a report from former Texas Governor John Connally, now Reagan’s campaign finance director who had helped box, with Shackley’s help, the President into the White House’s Rose Garden during the crisis, that Carter had worked out an “October Surprise” with Tehran after all.

This caused him to activate Allen. Robert Parry has explained in “The Consortium: Bush & a CIA Power Play”:

‘George Bush,’ Allen’s notes began, ‘JBC (Connally) – already made deal. Israelis delivered last wk. spare pts. via Amsterdam. Hostages out this wk. Moderate Arabs upset. French have given spares to Iraq and know of J. C. (Carter) deal w/Iran. JBC (Connally) unsure what to do. RVA (Allen) to act if true or not.’ (consortiumnews.com)

In another column, Parry added about Bush’s role: “Whenever Allen knew more, he was to relay information to ‘Shackley (sic) via Jennifer’ (Fitzgerald, Bush’s infamous secretary).” (“Clouds over George Bush,” Dec. 29, 1998, ibid.) When Allen’s queries failed to resolve the confusion, he activated Shackley.

The Agency’s former DDO was just the man to activate a programmed assassination at the drop of a hat, as former DCI Richard Helms had noted earlier – what the emergency required as there was no time to indoctrinate another Candidate.

Recently, he had mysteriously gotten rid of Frank Nugan of the Nugan Hand Bank in Australia when it became bankrupt – what risked exposing the Secret Team’s dirty tricks in the illegal drugs trade with America if he was not silenced.

Shackley’s successor, John McMahon, supervised the work of the Stanford Research Institute which was still developing “remote viewing” – the projection of words and images right into patient’s brains by machines and psychics – despite Koslov’s attempts to kill it off.

In 1995, McMahon admitted that the Agency had spent $20,000,000 on remote viewing research. “McMahon has, according to Philip Agee, the whistle-blowing exile, an affinity for ‘technological exotics’ for CIA covert operations,” Alex Constantine wrote in Virtual Government.

Most of the program’s “empaths” – victims – came from Ron Hubbard’s Church of Scientology, and Dr. West provided medical oversight for the psi experiments. West conducted his own on the “phenomenology of disassociate states” – the creation of people with multiple personalities.

Thanks to research by Yale’s Jose Delgado, California’s Dr. Ross Adey, Walter Reed Hospital’s Joseph Sharp, and DOD-funded J. F. Scapita, Dr. Elizabeth Rauscher, of San Leandro’s Technic Research Laboratory in the Bay area, was prepared to produce any kind of human behavior by directing extremely low frequency (ELF), electromagnetic waves of words and images into victim’s brains.

This technique permitted handlers to quickly create robot killers, provided they had willing victims, and were able to move them around at will. Ideally, they would want to find someone who had a love-hate relationship with the proposed target.

One just had to find a candidate who could be easily persuaded to do the evil deed with the appropriate psychic driving without any calculation or reservation. Then it was just a question of getting the controlled killer into position for killing the target on cue – what could be managed nearby with the proper electronic equipment.

It was like having a home-deliverty assassination service.

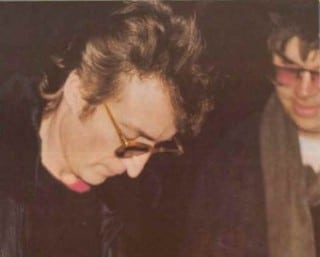

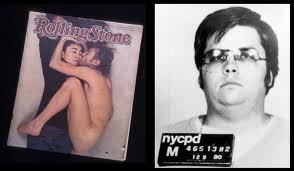

The same day, October 27th, that Shackley was alerted to take action, Mark David Chapman, a Hinckley lookalike – who had quit his job when Hinckley’s mission had ended, and signed out in Lennon’s name as if he were the target, only to cross it out before adding his own – started preparing to assassinate the famous Beatle, buying a .38-caliber Charter Arms Special in a Honolulu gun shop. (Fred McGunagle, Mark David Chapman, Chapter Six – “To the Brink and Back,” p. 2)

Hinckley was no longer available to go after anyone, being back in Denver under the care his parents had arranged with psychologist Dr. John Hopper after he had taken an overdose of antidepressants.

Chapman, who long had been of two minds about the former Beatle, had been ready for a similar assignment for a month, having been put through the psychological wringer the previous two months.

Chapman, the same age as Hinckley, and born in nearby Fort Worth, was another product of a dysfunctional family, though it took longer for him to descend to Hinckley’s state.

Then, just when he had miraculously gotten married, and worked himself out of debt, Chapman fell into a similar mental frenzy, believing increasingly that he was becoming Holden Caulfield in J. D. Salinger’s The Catcher in the Rye, even writing Hawaii’s Attorney General about the necessary procedure for changing his name. (McGunagle, p. 1)

At the time, Chapman was working as a maintenance man at the Castle Memorial Hospital, under the supervision of psychologist Leilani Siegfried, after its therapists had nursed him back to health from a suicide attempt.

While Chapman, a Hinckley copycat, could have been positioned to shoot Carter too, it would have been extremely difficult, and the shooting of Lennon would still be efficacious at the polls.

Chapman indicated that he had a few other high profile targets, one added as recently as October 1980 when Carter captured the public’s fancy, on his assassination list when he went before the NY State parole board after 20 years incarceration, the names of whom were so sensitive that it redacted them from the published report.

Lennon’s murder, it was assumed, would send liberal elements and the beat generation in the American electorate into a tailspin, and any violence, like burning down Harlem, would rally conservative American voters flocking to the voting booth for Reagan, as had happened for Nixon after the MLK and RFK shootings.

Lennon had drawn the ire and interest of MI5, and the FBI because of his songs of peace, and support of radical causes, especially the IRA’s, while taking drugs since the Nixon years (Fenton Bressler, Who Killed John Lennon?, excerpts, Part 2, pp. 2-3, www. shout.net/-bigred/lennon).

John and Yoko unwisely considered themselves like comedians Laurel and Hardy when it came to serious political business until it was far too late.

Lennon discounted the idea that CIA could have gotten rid of artists like Jimmi Hendrix, and James Morrison to quell radical ardor until his last days, only to concede to Krassner: “Listen, if anything happens to Yoko and me, it was not an accident. (Krassner, p. 215, emphasis Lennon’s)

The Agency had far more reason for wanting to fix the unexpected permanent residents in America for underestimating the consequences of taking drugs, especially LSD, and of MK-ULTRA operations than the British and American security services, and few would suspect it having done so.

Making the taking of such drugs much less criminal, and mainline would also undercut the illicit drug business that Shackley had been leading for years.

While the surprisingly well-heeled Chapman, whose source has never been adequately identified, set off for New York, like Holden Caulfield in the Salinger novel, on October 30th, splurging like Arthur Bremer at the Waldorf while stalking Nixon and Wallace, he allegedly failed to procure ammunition for his revolver when he bought it, requiring a trip to Atlanta to make up for the deficiency.

Actually, it would have been most easy for anyone to purchase ammunition in New York.

In the meantime, Carter’s last-minute effort to free the hostages through negotiation had been trumped by Bush and Allen bribing the Iranian Hostage Policy Committee’s Mohammad Behesti – thanks to a tipoff by Donald Gregg in the Carter National Security Council – who accompanied them, about the state of the President’s efforts.

This was apparently the cause of the delay, and by the time Chapman returned, shooting Lennon had become meaningless with Reagan’s election, his handler persuading him to return to his wife Gloria in Hawaii in the hope of regaining a normal life.

There were the strongest operational reasons, though, for this not being allowed to continue. A cured Chapman, his CIA handlers in the “remote viewing” program soon feared, might well recall how he had been maneuvered to kill Lennon, eager to tell all about the regime the Agency had put him through.

More sinister elements in the program rued the loss of an actual operation which would determine if a patient could really be driven directly to shoot a target wherever it appeared. As typical scientists, they were obsessed with seeing if their push button approach to assassination really worked.

Most important, Reagan’s people wanted a diversion to direct the people’s attention away from his “October Surprise,” the return of all the hostages being postponed until after his inauguration to prevent further speculation.

No sooner, though, did Reagan hint that he might have pulled off an “October Surprise” of his own than Chapman’s Castle Memorial therapist started winding him up again.

This resulted in his having such a shouting match with supervisor Siegfried that he was obliged to resign, resulting in threatening phone calls, and bomb threats to various parties – reminiscent of when Kaczyinski went off the rails.

The apparent loner “… spent his days harassing a group of Hare Krishnas who daily appeared in downtown Honolulu.” (McGunagle, “Is That All You Want?,” p. 1)

Arriving back in New York on December 6th, Chapman planned to kill Lennon the next day, the anniversary of the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, a fitting reminder to Yoko Ono of the betrayals.

After a spate of psychic driving Chapman acted as if he were a close associate of Lennon’s while living as if he were a nobody without a friend in the world. He bought a poster intended to screw up his courage, spotted a photograph of the former Beatle on a newsstand advertising an interview with the Lennons to focus his attention.

Next he purchased a copy of Lennon’s latest albumn to remind himself of his words, and finally bought a new copy of The Catcher in the Rye to renew his hatred of the world’s biggest phony – the image, sound, and words which were to trigger the shooting by impulses into his brain when he was in position.

In doing this programming, though, Chapman was so engrossed that he missed a few opportunities to kill Lennon.

When Lennon finally came into the picture, Chapman couldn’t bring himself to shoot him because he was so friendly, open, and generous.

Instead of allowing Chapman to go back to Hawaii with the signed Lennon album, and possibly a photograph of the friendly Beatle handing over the prized possession to this apparent nobody, his handler so bombarded him with negative impulses during the night at the Sheraton that he was back the next night at the Lennons’ Dakota residence to finish the job.

There was no way that Chapman could escape now, as any remission from what he had been through would be more dangerous than ever, given the ever increasing conspiratorial activities by Reagan’s people.

The negative driving finally won, as Chapman later explained: “He walked past me, and then a voice in my head said, ‘Do it, do it, do.’ over and over again, saying ‘Do it, do it, do it, do,’ like that.” (McGunagle, ch. 8, p. 1)

And Chapman, after getting Lennon to turn, and show his face, did it, and then, after preparing himself for the arrival of the police, resumed reading Salinger’s novel.

While Lennon’s assassination had the expected belated effect upon the American people, it served no useful purpose. In fact, it brought Hinckley out of his drug-related fantasies with a vengeance. He was so upset by Lennon’s assassination – the Beatle being the one person he truly loved – that he went to New York, and attended a service in Central Park to honor his contributions to music and art.

As the debate about who was behind it, and the release of the prisoners in Iran grew, Hinckley increasingly sided with, of all people, Mae Brussell who explained Lennon’s assassination thus:

“It was a conspiracy. Reagan had just won the election. They knew what kind of president he was going to be. There was only one man who could bring out a million people on demonstration in protest at his policies — and that was Lennon.” (Bresler, p. 1)

Under the circumstances, questions about Hinckley’s stability, and allegiances started growing in official circles. On January 13, 1981, Mae Brussell noticed a white sedan, with a man and woman sitting inside, parked across the street from her house.

The conspiracy theorist, as she explained in a 14-page letter to FBI Director Clarence Kelly, thought that the pair were conducting a surveillance on her, and she characteristically confronted them about it.

While the woman in the car explained that they weren’t, the man hardly said anything.

“When Reagan was shot, Mae recognized photographs of the accused assailant as the same quiet young man she had seen parked in front of her home.” (Vankin and Whalen, p. 64)

After the Bureau checked out this claim, and others by the noted conspiracy theorist, it concluded conveniently in a memo that she was “mentally unstable”, whose theories were not to be taken seriously.

Of course, the FBI might have concluded differently if it had realized that the person, probably his former handler, in the while sedan with Hinckley was trying to rekindle his hatred of Brussell for having stopped his romance with her daughter a few years before rather than conducting a surveillance on her. Obviously, it didn’t work as Hinckley increasingly had the President or the Vice President in his sights.

Then there were stories in the Washington press that someone was stalking the Vice President, causing the city’s police and the Secret Service all kinds of concerns which Bush was denying as quietly but as angrily as he could.

Then there was the dinner date that his son Neil had scheduled with Hinckley’s older brother Scott on the night after John’s assassination attempt on Reagan. (ibid., pp. 332-3)

People in the know about John’s state of mind and intentions were obviously concerned about what he was up to.

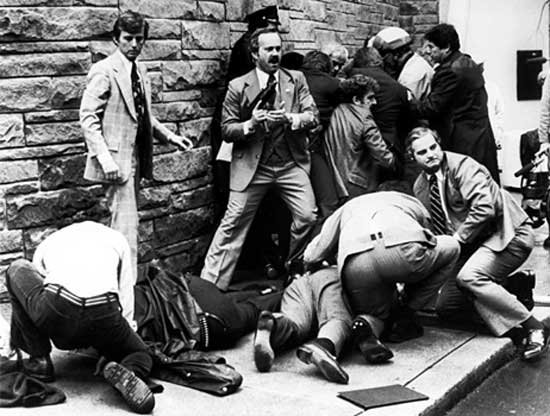

Despite further attempts by John’s handler to prevent him from doing anything drastic, though she did not report the risk to law-enforcement officials for fear of disclosing the whole covert operation, he was among the small group awaiting Reagan’s exit from Washington’s Hilton early on the afternoon of March 30, 1981.

He started firing his .22 caliber pistol, armed with “devastator” bullets, at the rather loosely protected President, the last of which ricocheted off the limousine’s door, and deeply penetrated the President’s thorax, narrowly missing his aorta.

The Secret Service had apparently not followed its usual formation in protecting Reagan, apparently not to highlight its increased concerns about his safety in apparently such a risk-free area, and was slow to react to his wound, thinking it still impossible for any assassin to actually have hit him.

[youtube 3Bj6aOgfcJU] – Reagan Shooting

These miscalculations almost cost Reagan his life, and a new batch of data for conspiracy theorists to work with.

The Agency, though, did not need any new revelations to mend its ways somewhat.

Its trials and tribulations with Hinckley taught it to avoid the use of any kind of Manchurian Candidate in future.

But it was willing to use other means to silence its enemies and to lend out its expertise to allied services, particularly Israel’s Mossad, if necessary, as we shall see.

Trowbridge Ford, now 81 …Military family, Army Counter Intelligence during the Korean War, reporter, Columbia Phd, and assassination survivor, now living in Sweden under the protection of their security services.

These are the kinds of writers that VT is laboring to bring our readers, people who have put not only their labors but lives on the line to bring stories to our readers that have been hidden for all the various reasons.

While this longer, magazine format of presentation is generally not viewed as suitable to short attention span internet readers, the VT board will continue developing this format as the older big stories require more space to frame them properly.

Trowbridge Ford (1929 – 2021) was the son of William Wallace Ford, the father of the US Army’s Grasshoppers.

He attended Phillips Exeter Academy, and Columbia University where he received a Ph.D. in political science after a stint in the Army’s Counter Intelligence Corps as a draftee during the Korean War, and after being discharged, worked as the sports editor and a reporter for the now-defunct Raleigh Times.

Thought academia was the thing for him. He was quite satisfied teaching all kinds of courses about European and American politics while writing his dissertation about an under-appreciated British politician, Henry Brougham, who became the Lord Chancellor of the famous Reform Government (1830-34).

At the same time, Trowbridge became most interested in the role that A. V. Dicey, a famous Oxford legal professor, played in settling the Irish question – another figure that historians didn’t think did much about. It was while he was doing research on the dissertation at the British Museum in London that President Kennedy was assassinated, and it slowly led him to take a dimmer view of academic life, especially when joined by campus protests over the growing Vietnam War. He was fired by two institutions of higher learning because of his protests against the war.

When the Vietnam War finally ended, he got involved in researching the Dallas assassination, and his first serious efforts about it appeared in Tom Valentine’s The National Exchange in 1978 – what Fletcher Prouty thought was quite good, just urging him to go higher in the Agency and the political world for the main culprits.

He slowly started doing this, ultimately deciding to retire early in 1986, planning on finishing his Brougham biography while living in Portugal. While he did this, he had made too many enemies with the White House not to be punished – first by attempts to establish that he maliciously tried to destroy Richard Nixon during Watergate by libeling him, and when he died, DCI George Tenet tried to have me killed by poisoning – what would make his death look like a suicide or a natural one.

As a result of this, once he had finally determined the cause, he moved to Sweden to not only save his skin but also investigate and write about assassinations, covert operations, ‘false flag’ deceptions, preventive wars, weapons development, and their use, etc. He passed away in 2021.

ATTENTION READERS

We See The World From All Sides and Want YOU To Be Fully InformedIn fact, intentional disinformation is a disgraceful scourge in media today. So to assuage any possible errant incorrect information posted herein, we strongly encourage you to seek corroboration from other non-VT sources before forming an educated opinion.

About VT - Policies & Disclosures - Comment Policy