Medical researchers and veterans advocates eagerly await the findings of a University of Wisconsin-Madison study on Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) focusing on how brains process anxiety and anticipation. From a November 2009 UW-Madison press release, UW-Madison Launches Study of Iraq and Afghanistan Veterans, drawing increased attention as troops are coming home.

Medical researchers and veterans advocates eagerly await the findings of a University of Wisconsin-Madison study on Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) focusing on how brains process anxiety and anticipation. From a November 2009 UW-Madison press release, UW-Madison Launches Study of Iraq and Afghanistan Veterans, drawing increased attention as troops are coming home.

Madison, Wisconsin – Why do some veterans return from war able to move beyond the horrors they experienced while others suffer ongoing Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD)?

The answer may lie in differences in how their brains process anxiety and anticipation.

A team of psychiatrists at the University of Wisconsin and the William S. Middleton Veterans’ Hospital in Madison has launched a large clinical study aimed at finding better treatments for veterans returning from Operation Enduring Freedom in Afghanistan and Operation Iraqi Freedom.

“We became aware of how many veterans are returning from Iraq and Afghanistan with serious PTSD, and were interested in finding out the best ways to help,” says Jack Nitschke, PhD, a psychiatry professor in the UW School of Medicine and Public Health. His collaborators are Eileen Ahearn, MD, PhD, and Tracey Smith, PhD, both UW clinical psychiatry faculty who practice at the Veterans’ Hospital.

PTSD is a debilitating condition that often follows a terrifying physical or emotional event causing the person who survived the event to have persistent, frightening thoughts and memories, or flashbacks, of the ordeal. People with PTSD often feel chronically, emotionally numb; the disorder is associated with higher rates of alcohol and drug abuse and suicide.

Nitschke, who treats severely anxious patients (in the psychiatry department at the Wisconsin Psychiatric Institute and Clinics) and studies brain differences in the Waisman Laboratory for Brain Imaging and Behavior, suspects those veterans who suffer the most debilitating PTSD have brain differences that set them up for the disorder.

“A lot of people go to war; some are able to get over the experiences with talk and processing, whereas others are traumatized,” Nitschke says. “What is different about the brains of these people that cause the anxiety to become so overwhelming?”

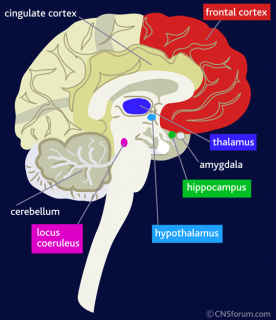

Some of Nitschke’s earlier research used functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) to watch how the brain processes anxiety. He found that people with several common anxiety disorders show stronger activity in the amygdala in some situations. In other words, people with this signature of the anxious brain worry more and can experience debilitating consequences.

Another of Nitschke’s recent studies, published in March in the American Journal of Psychiatry, showed that patients who had greater anticipatory activity in a different area, the anterior cingulate, responded better to treatment with venlafaxine (Effexor).

In the newest study, about 120 Iraq and Afghanistan combat veterans will be divided into four groups:

All groups will receive fMRI scans before and after the eight-week treatment regimen to see which approach works best to normalize the brain after combat.

Nitschke says that PTSD isn’t only about what happened during the war, in the past. It also involves anxiety about the future, which leads to numbing activities such as drug and alcohol use, hypervigilance and avoidance behavior. Many with the disorder, he says, avoid social situations and other people because they fear that stress or noise will trigger flashbacks.

“This is what is so debilitating about the disorder,” he says. “People worry that they’re going to have severe flashbacks or a panic attack while they’re at work or on the bus. It’s this worry about future events that can keep them in their homes and turn them into recluses.”

This research is funded by the UW Institute for Clinical and Translational Research, the Dana Foundation, and the U.S. Defense Department.)

ATTENTION READERS

We See The World From All Sides and Want YOU To Be Fully InformedIn fact, intentional disinformation is a disgraceful scourge in media today. So to assuage any possible errant incorrect information posted herein, we strongly encourage you to seek corroboration from other non-VT sources before forming an educated opinion.

About VT - Policies & Disclosures - Comment Policy