Exploiting Afghan Tribal Militias for an Optimal Counterinsurgency Campaign

Exploiting Afghan Tribal Militias for an Optimal Counterinsurgency Campaign

By Khalil Nouri STAFF WRITER FOR VETERANS TODAY

The U.S. cannot politically or militarily afford an open-ended escalation of the war in Afghanistan, nor can it opt for an incremental “halfway” strategy that could fail to sustain the psychological justification for a continued Western presence in the fighting; but neither approach can win the hearts and minds of Afghans. That is why, the Community Defense Initiative (CDI) is now being enthusiastically backed by General Stanley McChrystal; he is pushing for a local-based tribal approach, modeled on the program in Iraq that built up Sunni neighborhood militias. It requires fewer U.S. troops, cost less and has a more immediate impact than the traditional policy of growing and training a central government army and police force. In support of this approach, British Prime Minister Gordon Brown recently told the British parliament that Britain advocated a shift in strategy that would favor “hard-headed realism” and work with the “grain of Afghan tradition.” However, even this approach will fail without reliable tribal partners.

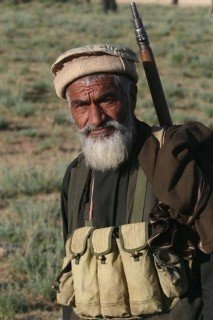

The new strategy, to create so called “pockets of tribal resistance” ( “Arbakai” in the Pashtu language), involves embedding US special forces into armed groups, including disgruntled insurgents, to give them training and support to fight the Taliban. But many Afghans and Afghan-Americans believe that no matter how well-trained or Afghan-culture sensitive US Special Forces are, they will never know enough about a specific local area and its indigenous norms to carry out their daily counterinsurgency campaign effectively; because the people will never trust them enough to share everything.

The “traditional means for managing violence” in Afghanistan creates the conditions under which the Taliban can emerge and deceitfully sell themselves as neighborhood Gladiators who protect regular folks from looting warlords. In Eastern Afghanistan, with very few exceptions, the traditional political authorities are village or tribal elders and local mullahs or maulavis; they do not share power equally and, do not exist in a “traditional” sense (that is, in-phase with how pre-Soviet invasion communities functioned) and they cannot be trusted to rejuvenate the social and moral fabric of society nor share intelligence with foreign “occupiers”.

Setting the above example in context, many tribes are susceptible to Taliban influence because they often feel weak relative to other tribal elements, and they feel totally helpless in the face of warlords. The Taliban provide instant justice and some social services in vast areas of lawlessness where traditional norms vary from village to village or tribe to tribe.

One must bear in mind that, the importance of understanding the strength and degree of tribe and clan-based loyalties and what happens when foreign occupiers interfere in the traditional order of balance and stability that took thousands of years to set in place; foreign displacement of Pashtun authority will always result in resentment exponentially within layers of tribal hierarchy.

For real solutions, one must understand Pashtun tribal culture; there are some 60 Pashtun tribes and 400 sub-tribes, many at odds with each other. Since the 18th century, supremacy has been held almost exclusively by the Durrani tribal federation. The NATO invasion of 2001, toppled the Taliban, but pushed the Soviet caused tribal-imbalance further out of balance; and as a consequence, it has created the current all around state of distrust.

Regarding the “Arbakai” system; despite many governments emerging and disintegrating, Arbakai has proven its invariable viability and indispensable reliability for centuries. However, the system is based on the normal Pashtun tribal code of “Pashtunwali”, which governs a community policing system grounded in volunteer grassroots initiatives. Volunteers are unpaid, they are not hired by a government or individual person, or a company; and they carry responsibilities that are approved and recognized as fulfillment of the common and public good.

Their main function is to put into action the decisions made by a tribal assembly of elders (known as Jirgah), to maintain law and order and protect and defend borders and boundaries of the tribal community. The system operates in a “default upward mode”, financed by the community and its allegiance is only to the tribe.

Moreover, the system is designed to be separate from political and economic objectives of influential individuals and government authorities. Per a Crisis States Research Centre’s study, “It must be controlled by a representative group that will make collective decisions on the basis of equal and inclusive participation.”

Given the above conditions, our view suggests warnings that could severely derail the (CDI) initiative; first, the placement of U.S. Special Forces alongside locally armed tribal fighters inside Afghan villages and towns is very alarming; because the war is expected to escalate in inhabited areas, innocent lives could be lost; consequently greater resentment towards the West will follow.

Second, if (CDI) were to be discarded, and the Afghan government took control of “Arbakai” counterinsurgency operations, the differing management structures could pose problems. In Afghanistan, the police and other security sector institutions follow a bureaucratic hierarchical management structure. On the contrary, the “Arbakai”, as mentioned, is directly controlled by the communities. It will be difficult to reconcile these structures. Consequently, the “Arbakai” would lose its integrity if it were incorporated into a bureaucratic structure.

The very idea behind a local militia is to establish then arm tribal volunteers (which could pose a significant challenge to central government authority). Conflicts between “Arbakai” and the Afghan security apparatus, or U.S. troops, can arise if the “Arbakai” feel community interests’ clash with central government or American interests. This is a recipe for undermining counterinsurgency and further disconnecting people from their government. However, the adoption of a community based system by the state security sector seems unlikely.

Third, the prospect of re-empowering militias after billions of international dollars were spent, after the U.S. led invasion in 2001, to disarm illegally armed groups is also worrisome.

Given the complexity and intertwined nature on the ground, there is only one Afghan solution; as quoted above regarding “Arbakai”, “It must be controlled by a representative group that will make collective decisions on the basis of equal and inclusive participation.” But who can be the ostensible representative group that could preserve the (CDI) in the traditional form of Afghan tribal framework? Our native suggestion is the “National Coalition for Dialogues with the Tribes of Afghanistan” www.ncdta.org. This organization was established in 2004 under a core group of tribal elders for the sole purpose of uniting all the tribes of Afghanistan as one.

It is based on the premise that it’s a movement of the People by the People and for the People of Afghanistan, and it stands on four pillars: Islam-Nation-Tribes-Independence. It’s self-sustained and is not associated with any political party or supported by any foreign government. This organization can act as a strong functional support link between the tribal militias, NATO troops, and the Afghan government.

And finally, to offset the Pashtun theory of tribal ethics; “me against my brother, the two of us against our cousins, the four of us against our neighbors, all of us against the tribe across the ridge, all those tribes together against strangers…” we therefore, must give the NCDTA a chance to do what it was organized to do before risking further blind escalation towards total failure.

Khalil Nouri and Terry Green are the cofounders of New World Strategies Coalition Inc., a native think tank for nonmilitary solution studies for Afghanistan. http://www.nwscinc.org

Khalil Nouri was born in an Afghan political family. His father, uncles, and cousins were all career diplomats in the Afghan government. His father was also amongst the very first in 1944 to open and work in the Afghan Embassy in Washington D.C., and subsequently his diplomatic career was in Moscow, Pakistan, London and Indonesia. Throughout all this time, since 1960’s, Khalil grew to be exposed in Afghan politics and foreign policy. During the past 35 years he has been closely following the dreadful situation in Afghanistan. His years of self- contemplation of complex Afghan political strife and also his recognized tribal roots gave him the upper edge to understand the exact symptoms of the grim situation in Afghanistan. In that regards, he sees himself being part of the solution for a stable and a prosperous Afghanistan, similar to the one he once knew. One of his major duties at the beginning of Operation Enduring Freedom in Afghanistan in 2002 was advisory role to LTG Franklin Hegenbeck. He has worked closely with the Afghan tribes and his tribal exposure is well tailored for unobstructed cross-cultural boundaries within all Afghan ethnicities. He takes pride in his family lineage specifically with the last name “Nouri” surnamed from his great-grandfather “Nour Mohammad Khan” uncle to King Nader-Shah and governor of Kandahar in 1830, who signed the British defeat and exit conformity leaving the last Afghan territory in second Anglo-Afghan war. Khalil is a guest columnist for Seattle Times, McClatchy News Tribune, Laguna Journal, Canada Free Press, Salem News, Opinion Maker and a staff writer for Veterans Today. He is the cofounder of NWSC Inc. (New World Strategies Coalition Inc.) a center for Integrative-Studies and a center for Integrative-Action that consists of 24- nonmilitary solution for Afghanistan. The function of the Integrative-Studies division (a native Afghan think tank) is to create ideas and then evolve them into concepts that can be turned over to the Integrative-Action division for implementation. Khalil has been a Boeing Engineer in Commercial Airplane Group since 1990, he moved to the United States in 1974. He has a Bachelor of Science degree in Mechanical Engineering, and currently enrolled in Masters of Science program in Diplomacy / Foreign Policy.

ATTENTION READERS

We See The World From All Sides and Want YOU To Be Fully InformedIn fact, intentional disinformation is a disgraceful scourge in media today. So to assuage any possible errant incorrect information posted herein, we strongly encourage you to seek corroboration from other non-VT sources before forming an educated opinion.

About VT - Policies & Disclosures - Comment Policy