COMMUNICATING WITH THE PERSON WITH DEMENTIA/ALZHEIMER’S

COMMUNICATING WITH THE PERSON WITH DEMENTIA/ALZHEIMER’S

By Carol Ware Duff MSN ,BA, RN

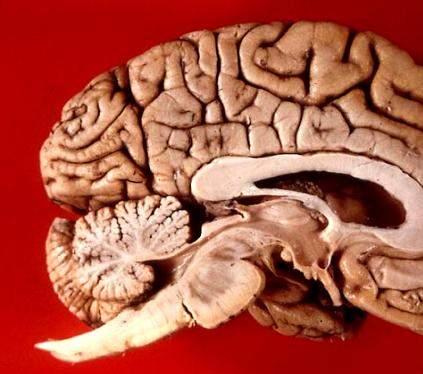

Dementia affects all areas of the brain including areas of memory and sensory inputs which are vital for communication.

The ability to store what was said in “short term memory” may be lacking in a person with dementia, making sharing everything from simple needs to more complex ideas very difficult. If the information cannot be temporarily stored, the ability to respond is lost.

Sometimes the person will store only part of what is said and will act on only that one part. The response may be correct for the message that is received, but there are many areas where the message can become garbled or misunderstood. Very often, a response, even if the question is understood, can be very different from what was meant.

Two areas of communication difficulty for your loved one may be:

- Expressing him/her self to others.

- Understanding what is being said to him or her.

What are problems the person with dementia has expressing him or herself?

- The failure to communicate can range from the occasional failure to find a word, changing words, or choosing words that are wrong, to an inability to express what he or she intends to say.

- Some people may be only able to communicate a few words of the thought.

- Others may ramble on, stringing words or phrases together.

- Your loved one may try to cover up communication difficulties by answering a question with a question, and when pressured, become defensive and say he or she is being bothered.

- Some people may start to use swear words or inappropriate language even if he or she has never used them before. Rarely is this behavior deliberate.

- With severe language problems, the person may only use a few words such as, “No,” when a response seems too difficult.

- Eventually the person with dementia may become totally unable to communicate using speech. This is particularly upsetting to family members who feel no longer able to talk with their loved one.

What are ways to help your loved one with expressing him or herself?

- If the person is having difficulty finding a word, try supplying the word, if this does not upset him or her.

- Ask the person to point to what he or she wants or is talking about.

- You might guess incorrectly, so be open, and ask if you are correct.

- Since relaxation encourages better communication, maintain a calm approach.

- Do not rush a person when he or she is trying to communicate. Continue to show both interest and attention.

- A picture board may be helpful. You may need to cut out magazine pictures of common activities and paste them on a board.

- Your loved one can then point to what he or she means or wants.

When a person cannot communicate, make sure he or she is comfortable by checking:

- Is his or her clothing fitting properly?

- Is the room temperature comfortable?

- Is he or she hungry?Has he or she been taken to the toilet recently?

- Is his or her skin free of sores, rashes, or irritations?

What are problems the person with dementia has with understanding others?

- Often people with dementia have difficulty understanding what others say to them and may not respond. This may be mistaken as difficult behavior.

- A person with dementia can quickly forget what he or she once understood. Never assume anything is known or understood from moment to moment.

- He or she may be able to read but not understand what he or she has read.

- Your loved one may not be able to understand or remember written directions.

- Your loved one may not understand what is spoken over the phone as opposed to face to face communication, nor recognize a voice without a face.

What can you do to improve your loved one’s understanding?

Verbal communication:

- Verbal communication is using speech to share ideas and feelings.

- Make sure the your loved one can hear and see. Sight and hearing may decrease with age.

- Get the attention of your loved one, make eye contact, and be at eye level.

- Use the person’s name and a calm, matter of fact approach every time you address him or her.

- Get rid of distracting noises and activities while trying to communicate.

- Use a lowered tone of voice if the person is hearing impaired and speak in a steady fashion.

- Begin conversations with orienting information such as, “It is now time to eat breakfast.”

- Ask only one simple question at a time and address only one task at a time:

- Break any tasks into several smaller steps.

- Use short words and simple sentences with exact words.

- Do not say, “Do you want to take a bath?” Instead say, “It is time for your bath.”

- Be ready to repeat yourself.

Non-verbal communication:

- A person can communicate with body movements, as well as his or her face, eyes, and hands.

- Your loved one can remain sensitive to nonverbal signs when he or she can no longer understand the spoken language.

- Think about how you present yourself.

- Be aware of non-verbal signals such as facial expression, body tension, and mood.

- Look to see if your loved one is paying attention.

- Look directly at him or her and look for body language to read.

- Use a neutral approach with humor and cheerfulness.

- Use gentle touch to communicate your message.

- Be pleasant, calm, and supportive, even if you are upset.

- Point, touch, hand your loved one items, demonstrate actions, and describe with your hands.

- Draw or show pictures or use the picture board.

The following are some websites to provide you with more information about communication.

AlzOnline: Ways to help communication. http://alzonline.phhp.ufl.edu/en/reading/communication.php

AlzOnline: Interaction –Tip sheet. http://alzonline.phhp.ufl.edu/en/reading/memorytips.php

Family CareGiver Alliance: Caregiver’s guide to understanding dementia behaviors. http://www.alsindependence.com/caregivers_guide_to_understanding.htm

References AlzOnline: Ways to help communication. Retrieved September 20, 2008, from http://alzonline.phhp.ufl.edu/en/reading/communication.php

Boyd, M. (2002). Psychiatric nursing: Contemporary practice (2nd edition). Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott.

Ignatavicius, D., & Workman, M. (2006). Medical-surgical nursing:Critical thinking for collaborative care (5th edition). St. Louis, MO: Elsevier Saunders.

Lewis, S., Heitkemper, M., & Dirksen, S. (2004). Medical-surgical nursing: Assessment and management of clinical problems (6th edition). St. Louis, MO: Mosby.

Mace, N., & Rabins, P. (2006). The 36-hour day: A family guide to caring for people with Alzheimer disease, other dementias, and memory loss in later life (4th edition). Baltimore, MD: The Johns Hopkins University Press.

Potkins, D., Myint, P., Bannister, C., Tadros, G., Chithramohan, R. Swann, A. et al. (2003) Language impairement in dementia: Impact on symptoms and care needs in residential homes. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 18(11), 1002-1006.

Robinson, A., Spencer, B., & White, L. (2007). Understanding difficult behaviors: Some practical suggestions for coping with Alzheimer’s disease and related illnesses. Ypsilanti, MI: Eastern Michigan University.

Romano, Donna M. (2004). Making the paradigm shift: Enhancing communication for clients with Alzheimer’s disease using a client-centered approach. Journal of the American Psychiatric Nurses Association 10(2). 81-85.

Developed in 2008 by Carol Ware Duff, RN at the University of Toledo for the Caregiver Consultation Center.

Carol Duff graduated from Nursing School at Riverside White Cross in Columbus, Ohio.

Carol Duff graduated from Nursing School at Riverside White Cross in Columbus, Ohio.

She has a BA from Bowling Green University in History and Literature and a Masters of Science in Nursing as a Nurse Educator from the University of Toledo School of Nursing.

She has traveled extensively and has written on military history, veterans health issues and related subjects. She is the mother of several children and 11 cats and 1 guinea pig.

She can be reached via email at: Thehertz@aol.com

Carol graduated from Riverside White Cross School of Nursing in Columbus, Ohio and received her diploma as a registered nurse. She attended Bowling Green State University where she received a Bachelor of Arts Degree in History and Literature. She attended the University of Toledo, College of Nursing, and received a Master’s of Nursing Science Degree as an Educator.

She has traveled extensively, is a photographer, and writes on medical issues. Carol has three children RJ, Katherine, and Stephen – one daughter-in-law; Katie – two granddaughters; Isabella Marianna and Zoe Olivia – and one grandson, Alexander Paul. She also shares her life with her husband Gordon Duff, many cats, and two rescues.

ATTENTION READERS

We See The World From All Sides and Want YOU To Be Fully InformedIn fact, intentional disinformation is a disgraceful scourge in media today. So to assuage any possible errant incorrect information posted herein, we strongly encourage you to seek corroboration from other non-VT sources before forming an educated opinion.

About VT - Policies & Disclosures - Comment Policy