by Mark Potter

![]() ANN ARBOR, Mich. – While growing up here many years ago, my brother, Alan, and I idolized Paul Rosasco, the World War II veteran who lived on the corner of our street. With rapt attention, we’d thrill to hear his stories of danger and high adventure in the South Pacific and would pester him to tell us more.

ANN ARBOR, Mich. – While growing up here many years ago, my brother, Alan, and I idolized Paul Rosasco, the World War II veteran who lived on the corner of our street. With rapt attention, we’d thrill to hear his stories of danger and high adventure in the South Pacific and would pester him to tell us more.

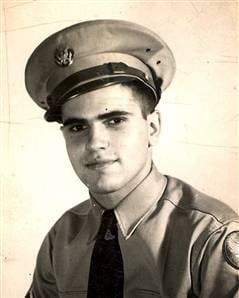

Courtesy of the Rosasco family

Now that Alan and I are much older, we understand that those stories back then were softened for young ears and actually came from tough memories of a brutal war. We’ve since heard the unvarnished version and have learned more about the injuries our neighbor suffered and about all the friends he lost. For that reason, and because of the life he lived in recent years, we actually came to admire him even more.

Paul Rosasco as a young soldier during World War II.

We are deeply saddened to learn that our friend and hero has just died at age 85. Now his remarkable story, which he was reluctant to draw attention to publicly while he was alive, can be shared with the blessing of his widow.

Enlisted for war

In November 1942, Paul Rosasco enlisted in the U.S. Army at the age of 19 and received his basic training in Florida. After advanced training in Illinois he then joined the 1896th Engineer Aviation Battalion in Virginia.

Near the small town of Elko, he and other trainees actually built a fake airport, complete with a runway, landing lights and empty buildings. It was a decoy to distract German bombers from the nearby Richmond Airfield should they cross the U.S. coastline. Luckily, the Nazi aviators never came calling.

After finishing up in Virginia, Rosasco headed by train for California. There he began a nearly-month-long voyage to New Guinea on a military transport ship with 3,500 men crammed aboard. After arriving in, Lae, New Guinea, he helped build airfields and housing for American forces fighting the Japanese. His second stop was Biak, where his company followed the infantry ashore during a bloody fight to wrest the island from Japanese control. As the Army engineers there built roads and a landing strip for U.S. bombers, Rosasco helped fend off attacks from hold-out Japanese soldiers.

Kamikaze attack

Rosasco’s next mission was the one that nearly took his life.

On New Year’s Day, 1945, his company joined an 80-ship convoy headed for the Philippines. Twelve days into the trip, near Corregidor, the convoy was attacked by 26 Japanese kamikazes. Rosasco’s transport ship, the Kyle Johnson, was struck and badly damaged by one of the planes. Of the 220 men in his company, 161 were killed in the attack.

When the plane hit the ship, it punched a huge hole in the starboard side and tore a second hole through an inside deck. Gasoline stored below for heavy engineering equipment then exploded in a massive fire. At the moment the plane crashed through the hull, Rosasco was below deck in a four-foot-wide pathway. Although knocked down, wounded by shrapnel and burned on his face and arms, he was able to escape the inferno by jumping into the water through the jagged hole made by the kamikaze.

Of the 15 men who ended up in the ocean, only nine survived.

Photo taken in 2008.

Suffering from a compound fracture on his right arm, he was able to stay afloat by hooking the exposed bone from his injured arm around a cable on a buoyant hatch cover. With his other arm, he held on tight to his best friend, Gus Miggans – unaware that Miggans was already dead.

Others urged him to let Miggans go, but Rosasco refused, shouting back, “Nah, he’s not dead, he’s sleeping.” He kept assuring his friend, “You’re gonna be OK, you’re gonna be alright.”

Another close call

While struggling in the water, Rosasco and the others there faced another threat. Japanese pilots were strafing the seas with machine-gun fire, trying to kill the helpless survivors. “I was saying those Hail Marys at 50 miles an hour,” he said.

One of the planes swooped over him, then circled back, heading straight in his direction. As the Japanese plane bore down and was getting close, it suddenly exploded. The pilot of a U.S. Hellcat fighter plane had come from above to shoot the Japanese Zero out of the sky.

After completing his attack, the American pilot flew low over the men in the ocean, tipped his wing and raised his hand. “He saluted us in the water,” said Rosasco. (Decades later Rosasco met that pilot and thanked him personally.)

About an hour into the ordeal which he said, “felt like forever,” Rosasco was finally rescued by the crew of a U.S. destroyer escort ship, while still holding tight to Miggans. It was then that he had to confront what others already knew, that his closest buddy had not survived the attack. Miggans was buried at sea.

In the months that followed, Rosasco and the other injured soldiers were treated for their burns and wounds aboard ships and at a hospital in New Guinea. When the war ended, he went to Tokyo, where shortly afterward he got word that he would be transferred home. He arrived back in Ann Arbor on Dec. 15, 1945, just in time for Christmas. Before leaving the Army, Rosasco was promoted to the rank of platoon sergeant. With so few survivors in his company, he grimly joked, “there was nobody else to give it to.”

A good neighbor

Back in civilian life, Rosasco married, raised two daughters with his wife, Maxine, and worked as a golf course manager, a quality control specialist for an auto company, a milk delivery man and a business office-manager for the University of Michigan hospital.

Photo taken in 2008.

In 1985, he retired and took on another important role as the unofficial – but much appreciated –neighborhood watchman, keeping an eye on the homes of vacationing residents, bringing in the mail, giving people rides and volunteering to help anyone in need.

He had the keys to most of the neighborhood homes and was the emergency contact person for my mother, whose rose bushes he also kept in shape. Whenever I came home, he and Maxine were always very welcoming. If my brother and I would prod him, he always had more stories to tell.

During one of my latest visits, I asked him how he felt when he returned home in 1945. “The war was over, it was wonderful,” he said. Feeling grateful to have survived he added, “I was luckier than hell.”

In recent years, though, with the few remaining veterans from his battalion passing on and the annual reunions no longer being held, he had more solemn thoughts about the young men who perished in that far-off war 64 years ago. “I throw out a name, I see a face,” he told me. He also wondered about how many people still cared about their sacrifices.

Particularly strong for him was the memory of his friend who died in the water near the Philippines. With a quiet pride few can ever earn, he said recently, “I hung on to Miggans.”

We are so very proud to have had Paul Rosasco as our neighbor, friend and hero.

ATTENTION READERS

We See The World From All Sides and Want YOU To Be Fully InformedIn fact, intentional disinformation is a disgraceful scourge in media today. So to assuage any possible errant incorrect information posted herein, we strongly encourage you to seek corroboration from other non-VT sources before forming an educated opinion.

About VT - Policies & Disclosures - Comment Policy